dimensions of a desert

1

I was a child the first time I heard about the desert. A cousin of mine came to Ceuta to spend the summer, he was reading a book about a desert planet where there was almost no life, just the colonists that were exploiting the only natural resource that was worthy, the spice, and local people that nobody understood how they could survive in such an inhospitable planet. They were organised as a tribe and they were able to adapt themselves to the nature, optimising the resources and appreciating what they had.

For me it was just a fiction novel with planets and people we would never see for real, but the possibility of the existence of that mysterious way of life stayed in my mind for ever.

2

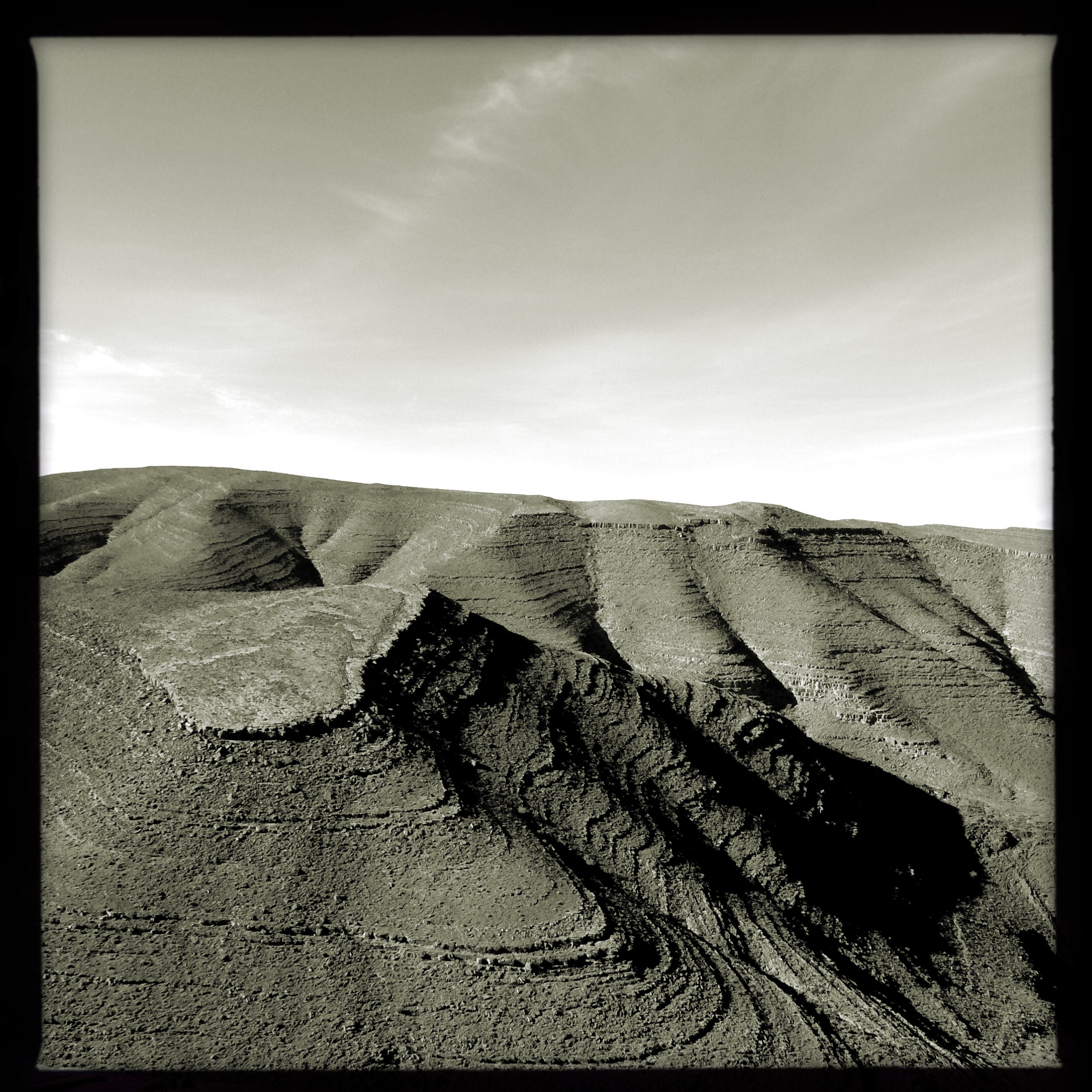

It wasn’t till 2010 that I had the opportunity to visit the Moroccan desert, thanks to Mohamed Arejdal, he invited me and Younès Rahmoun to explore his region, Guelmim. As everybody coming for the first time to the desert, it was amazing to discover another Moroccan culture, completely different from the one we know in the north, however I was a little bit disappointed because in my imaginary, the desert was always associated to dune landscapes and, to a lesser extent, to oases, nevertheless I just saw mountains, stones and a small palm grove.

3

In October 2010 I started to teach at the National School of Architecture of Tetouan, ENAT, (Morocco) and the relation with the desert became regular because once per year, we came to the south with the students to work on several issues proposed by authorities, in Tinejdad first and then in Zagora. These study trips were crucial for me in order to start to apprehend the desert ways of life. But I realised it was not enough to be interested on rammed earth architecture, I needed to take into consideration other issues like the geography of the regions, the hydrology, the ecosystems, the local economies, the social organisation, the architecture, the history of its tribes, their musics and dances… All these topics turn desert societies in amazing but also extremely complex communities.

But I realised it was not enough to be interested on rammed earth architecture, I needed to take into consideration other issues like the geography of the regions, the hydrology, the ecosystems, the local economies, the social organisation, the architecture, the history of its tribes, their musics and dances… All these topics turn desert societies in amazing but also extremely complex communities.

The main representative element of these societies (living in or around an oasis) is probably the ksar,an artificial space built to lodge inhabitants and to protect them from the attacks of other tribes, and from harsh weather. This was the first field of study with my students from Tetouan, a very interesting one because they were conceived as autonomous cities, with compacted constructions and reduced public spaces, besides, built with materials they could find in their own plot, it is really unbelievable to think a city can be built just with water, dirt and wood, an economy of means that was not an impediment to create complex outdoor and inner spaces. Nowadays, some of the ksour are still in use and even more, they have become references for new urban extensions in some places¹, putting in evidence the validity of some precepts (adapting the architectural habitat to weather conditions), based on common sense that should be applied in other cities if we really wanted to make them “sustainable”. That is to say, vernacular architecture in the desert could or should be next contemporary architecture in “western cities”.

Oulad M'hya, Zagora (2015)

At the same time, there was always a need to learn more about temporary architecture, represented in my mind by nomadic tents. That curiosity brought me to another essential moment, the encounter with a nomad family near Erg Chegaga in the Zagora province (Morocco). The time I spent with them (a day and a night) was short, but very revealing, at least from an ideological point of view (the freedom of settle down wherever and whenever they want), but there was something else that was engraved in my mind…

4

My interest on these autonomous cities, led me in 2013 to research further on the spatial organisation and the way the ksour were disposed on the territory.In the next two years I concentrated my researches on the architectural heritage of the Drâa Valley in the framework of Marsad Drâa, that I founded that year. An ensemble of 6 palm groves extending along 200 km from Agdz to M’hamid El Ghizlane. With the information provided by CERKAS, I went all over the valley, visiting all the ksour, casbahs and zawiyas (around 300). What started as an online catalogue, became an amazing learning process with different layers of knowledge and different dimensions, but they were all connected between them; territory occupation, urban development, construction systems, energy efficiency, environment, sociology, culture, history…

After months working in Zagora, I could have a better understanding of the reality of these regions, and the problems population must confront, like the extensions of urban centres, the abandon of ksour or the use of concrete to the detriment of rammed earth. However, I still had some questions unsolved. I did not know the raison some ksour were inside the oases and others outside, in fact I still know nothing concerning the relation between villages and their physical environments. I was only aware of the very deep feelings inhabitants have of belonging to a land, to a territory that provides them just what they need to live, moreover in such a extreme climate conditions, living in houses built by themselves, in their plots and with their own soil.

There were other premises that were wrong in my researches. I thought the population was concentrated in valleys and oases, because it was impossible to live in rocky mountains or in plains without water and vegetation, but it was not, because there are still nomads living in those lands, which made me think about these spaces, their limits, their relations, their adaptation to the environment… in summary nomad habitats.

Asrir, Guelmim (2017)

5

2015 During one of my stays in M’hamid El Ghizlane (Morocco), I met (thanks to my friends the Sbai brothers) an incredible man, Mokhtar, a nomad that used to go to Timbuktu (Mali) by walk, crossing the Sahara desert when the borders were still opened between Morocco and Algeria. I interviewed him several times (interview 1, interview 2, interview 3) and I always had the sensation I was in front of a wise, talking about spaces and stories rather from another world. A world made of sand inside a dome of stars. Further, what he said reminded me that fiction novel on desert planets I heard about 30 years ago. He talked about things I couldn’t believe or I couldn’t understand, worlds conformed by hallucinations, by people hidden behind the stars watching everything, by direct connections between humans and heaven… Stories seemed taken from a fiction novel, but he talked as if they were for real. I could not let pass the opportunity of researching on that world, not reading papers and books, but experiencing those dimensions of the desert, learning directly from the people that create the stories, and so the history of these regions.

Mokhtar, M'hamid El Ghizlane, Zagora (2016)

Mokhtar told me once about a night he felt asleep during a diner in a friend’s house, after a long journey walking in the desert, and how he woke up in the middle of the night screaming because he thought he has gone blind, in fact he did not go blind, it was just that there was no light on and the roof prevented him to see the stars. It looks a simple anecdote, but when you get used to sleep under the stars, you can understand what they mean for nomads.

6

With the purpose of researching on caravans and nomad life (in a practical way), I started a series of journeys in 2016, following the main routes caravans did through history in Morocco soil (the international situation and the conflicts in the Sahara region do not allow caravans between Morocco and Mali as before). Qafila Oula was the first one (organised with the help of Café Tissardmine) between Tissardmine (Errachidia) and M’hamid El Ghizlane (Zagora), a 300 km and two weeks trek I did with a local guide and two camels.

The research was not focus on a specific topic, but about everything related to caravans. The architecture and the habitat of these nomads, the way they get orientated in the desert, the importance of the moon, the presence or absence of water, their meanings and their challenges, the richness of the landscapes, the way they handle camels, the places they pass through, the history of the region and their territorial organisation, the cartographies done by travelers and armies, the ability to adapt themselves to the physical environment…

The caravan was also a physical and psychical challenge that needed a previous training in order to resist the harshness of the journey, and also the fears.

After Qafila Oula I needed some time to analyse and to process all the experiences gained during the journey, also to compare them with the knowledge I had grasped in the South these last years.

7

habitats en multidimension spaces

In “modern” cities HABITATs are conformed, mostly, by architecture, creating artificial spaces where people are supposed to be protected from inclement weather, modifying or even destroying the environment if necessary, which carry us to live in isolated compartments, losing our sensitivity and the contact with nature. A nature that is reduced to some green spaces if there are (sometimes those spaces are literally green, painted green, and they are accounted for as such in urban planning parameters). Unfortunately in lot of cities, a tree is an expendable element, a mere decorative object and green spaces are considered as a waste of money because those plots could be destined to dwellings.

In pre-Saharan regions, the lack of money and investments does not prevent people to create smart habitats (without architects or politicians), with materials they find in their own plots, using their techniques. They do not need much more because their conscience towards nature is completely the opposite than in “modern” cities. They need the palm groves to survive and they built cities (ksour) on their edge or inside them. For them, oases are paradises in the middle of inhospitable environments and they have to respect them (of course this mentality is nowadays changing, in the search of a supposed “modernity” that is making disappear material and immaterial heritage, palm groves and changing radically the habitat to another that will not resist the climatic conditions).

It is paradoxical to compare the importance of the environment in both habitats:

In “modern” cities you can find some green spaces inside them, in pre-Saharan (“traditional”) cities, you can find some houses and villages inside the green space. This fact, explained to “western” architects, seems to them an UTOPIA, but it exists and it is real in the Ziz and Drâa valleys (Errachidia and Zagora provinces).

But there is still another kind of habitat that goes further in the relation between architecture and environment, the nomad habitat, so far that there is not even architecture, just human beings facing nature. Because traditional tents (made of camel and goat wool) are used in some specifics cases, like sand storms, rain, cold weather, or when there is no tree to provide shadow and wind protection (if in pre-Saharan regions oases are considered as paradises, in the deep desert, a tree, a single one, is the paradise).

Most of the time nomads stay “outside”, day and night, they do not really need a roof to live, becoming these nomad habitats the minimal expression of Arquitecture, the NON ARCHITECTURE, where what matters is the connection between nomads, lands and stars.

Tighmert, Guelmim (2010)

Nomads near Erg Chegaga, Zagora (2012)

Habitats where,

a tree becomes a paradise

These habitats are also sacred places. A Malian friend told me that religion in the desert is (at least it was) an individual question, they do not need a mediator or an specific place to pray because the connection with “heaven” is done directly (architecture can even become an interference in a spiritual way). In the desert there is just the essential, just you and yourself. In that sense, when you experience the desert it is easier to understand Charles de Foucauld’s journey (Reconnaissance au Maroc) from an exploration trip to an inner one, becoming himself a hermit.

time and space

In Morocco there is already a huge difference between Northern and Southern cities concerning temporary and spatial dimensions, but when we arrive to areas inhabited by nomads, none of the references used to measure them are valid.

Time can change its speed several times a day. Space is variable, one kilometre can become into half, into two or into three. You can have the same speed sensation traveling at 300 km/h in a high speed train than walking at 5 km/h in a caravan (you realise 5 km/h is not a slow speed when you stop to take a picture and the camels keep going, in just two minutes they will be much farther than you could have imagined). Great open spaces can become small ones in just an instant. Your vital space can occupy thousands square meters or just one. The world can be around you, or in you. During the day, the physical reference we are attached to, is the soil, however during the night (specially with new moon) there is no soil, there are just stars and your new reference is inverted and so your mind. When you have no geographical reference (no mountains, no valleys, no sun or moon) you can even modify your perception of horizontality and you can suffer from vertigo, even in a plain, where the horizon can finish in a precipice or in a deep fosse.

On the contrary to what one might think, the less elements a landscape had, the more possibilities of creating our own worlds and planets we will have, due to multidimensional dysfunctions.

8

In November 2017 I will carry on my "interstellar journey" with another caravan, Beyond Qafila Thania, between M'hamid El Ghizlane and Tissint (200 km) and I will continue this ongoing research on non-architectures, times, spaces, worlds...

After years working in the desert, there is something I know now for sure; I need more time to understand the desert, probably, more than one life.

Ceuta, September 2017

Note: In 2020, as a continuation of these proposals on dimensions of a desert, I wrote, DIMENSIONS OF PERCEPTIONS.

all texts and images Ⓒ Carlos Perez Marin