The proximity of the Contemporary African Art Fair 1-54 did not allow the work of the first phase (demolition of the ground floor) to be undertaken and finished in January 2023, which is why the projet promoters (Eric and Mohammed) and the curators (Phillip and Chahrazad) decided to organise a contemporary art exhibition using the first floor apartments as they were, emptying them, cleaning them and installing general lighting in all the pieces. Given the visibility that this new space could have during the fair, we proposed to show elements of the architectural project so that possible investors could see that it was not just an idea or a desire but an architectural and urban rehabilitation project (the documents for the building permit application had been ready since October 2022) and a cultural project quite advanced in its reflections. But how do you introduce this type of information into a contemporary art exhibition? With texts, plans, 3D images, models…? It was also necessary to be consistent with the spirit behind Malhoun and finally the idea of presenting models was retained. The easiest would have been to start with models and techniques that we already knew to make architectural models, except that Malhoun could give us the possibility of doing otherwise and explaining the main concepts of the project using artisanal techniques. However, this positioning required a fairly complex change in our ways of thinking and making these models.

04.1 City block model

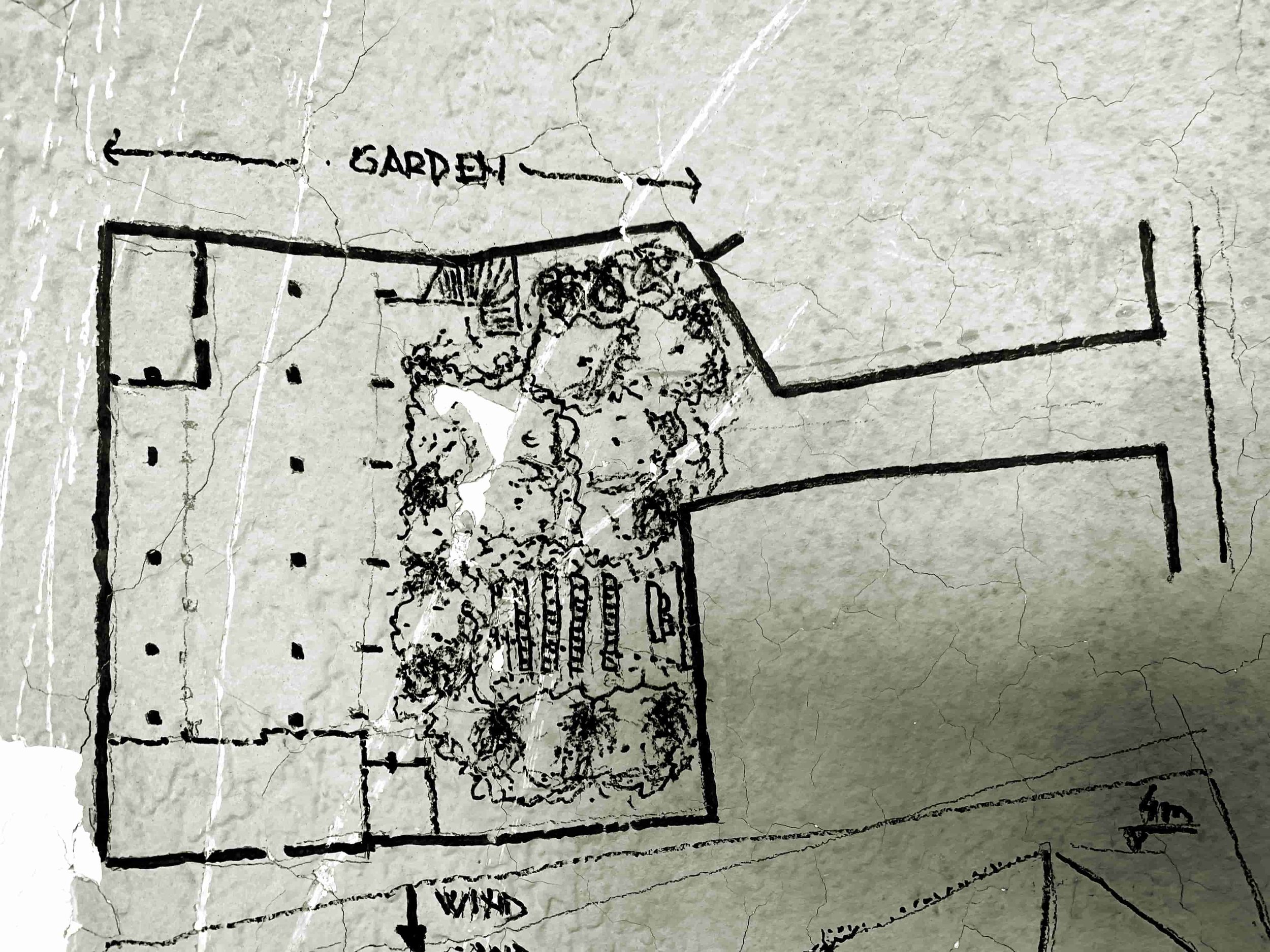

With Driss we started a series of discussions and reflections on various issues. We first had to decide what to show with these models, what were the particularities of the project, what we brought as architects to the evolution of Marrakesh and to the needs of the client. For Driss, it was important to note the visual axis that crossed the urban block from west to east and that if ever one day we freed up one of the adjoining garages to the west and opened a door on this facade, we could incorporate a pedestrian street into the public space, by facilitating access to the future garden which could also become public.

Malhoun - rue Mohammed el-Beqal axis

Malhoun - boulevard Abdelkrim el-Khattabi axis

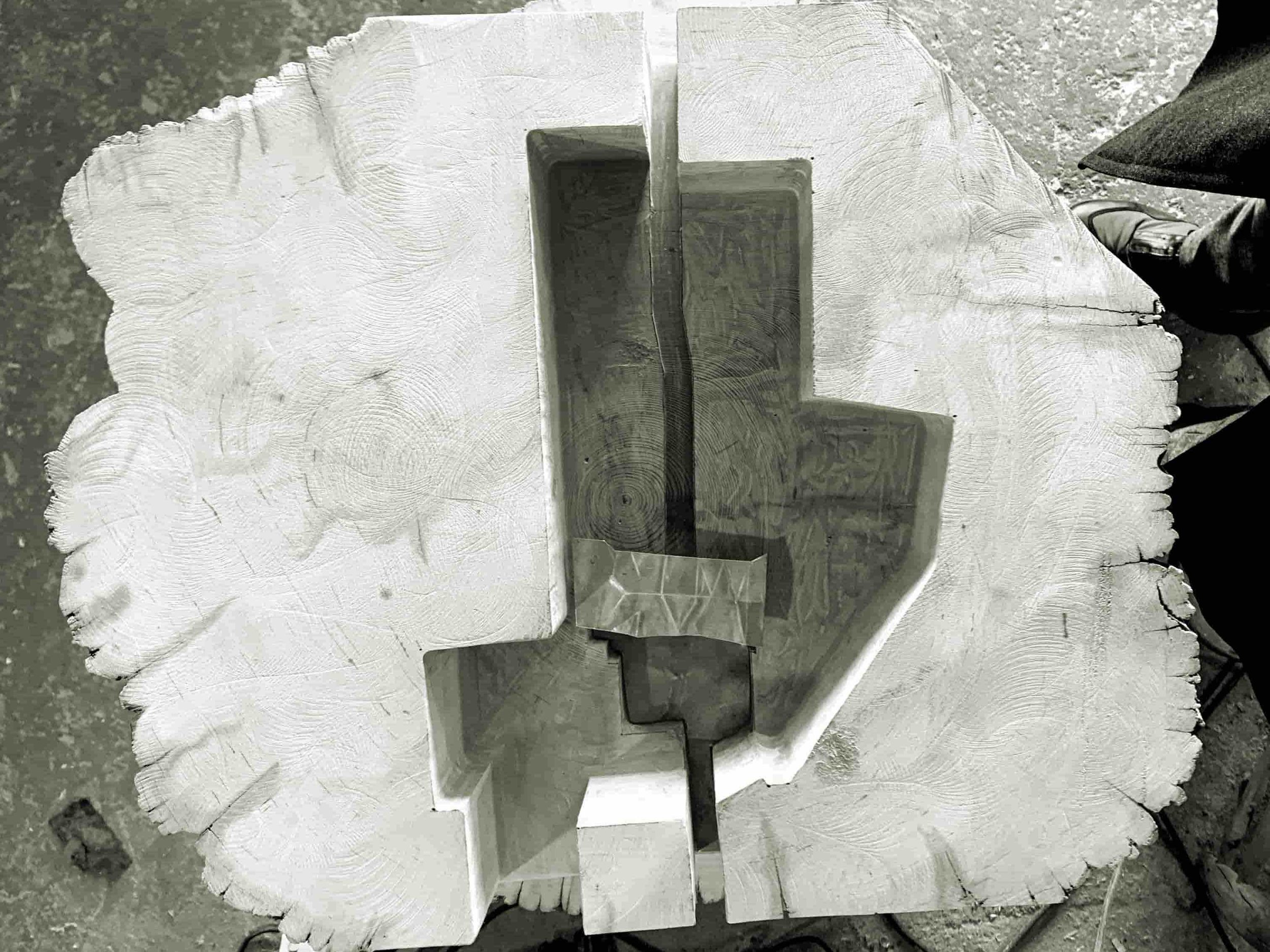

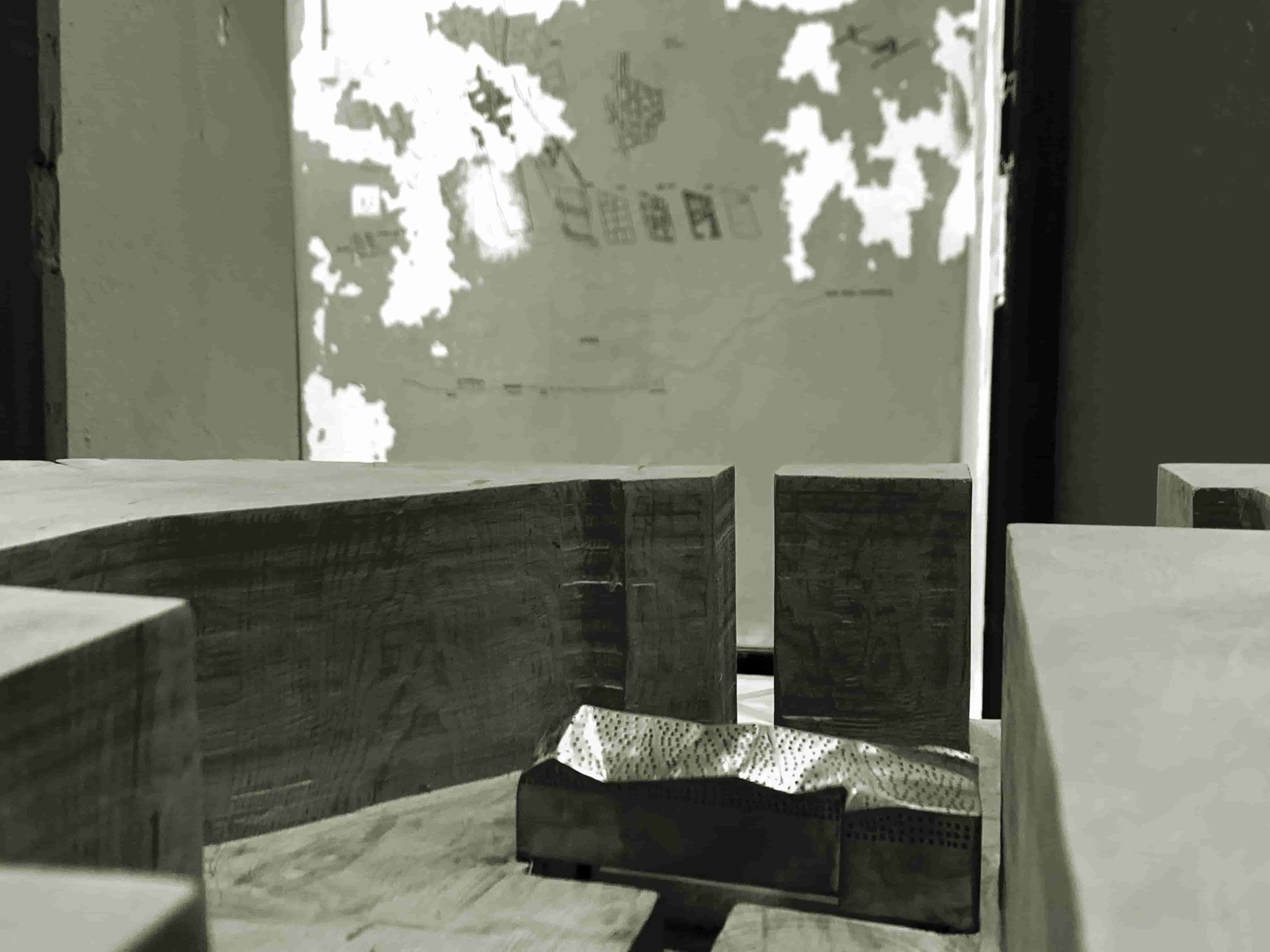

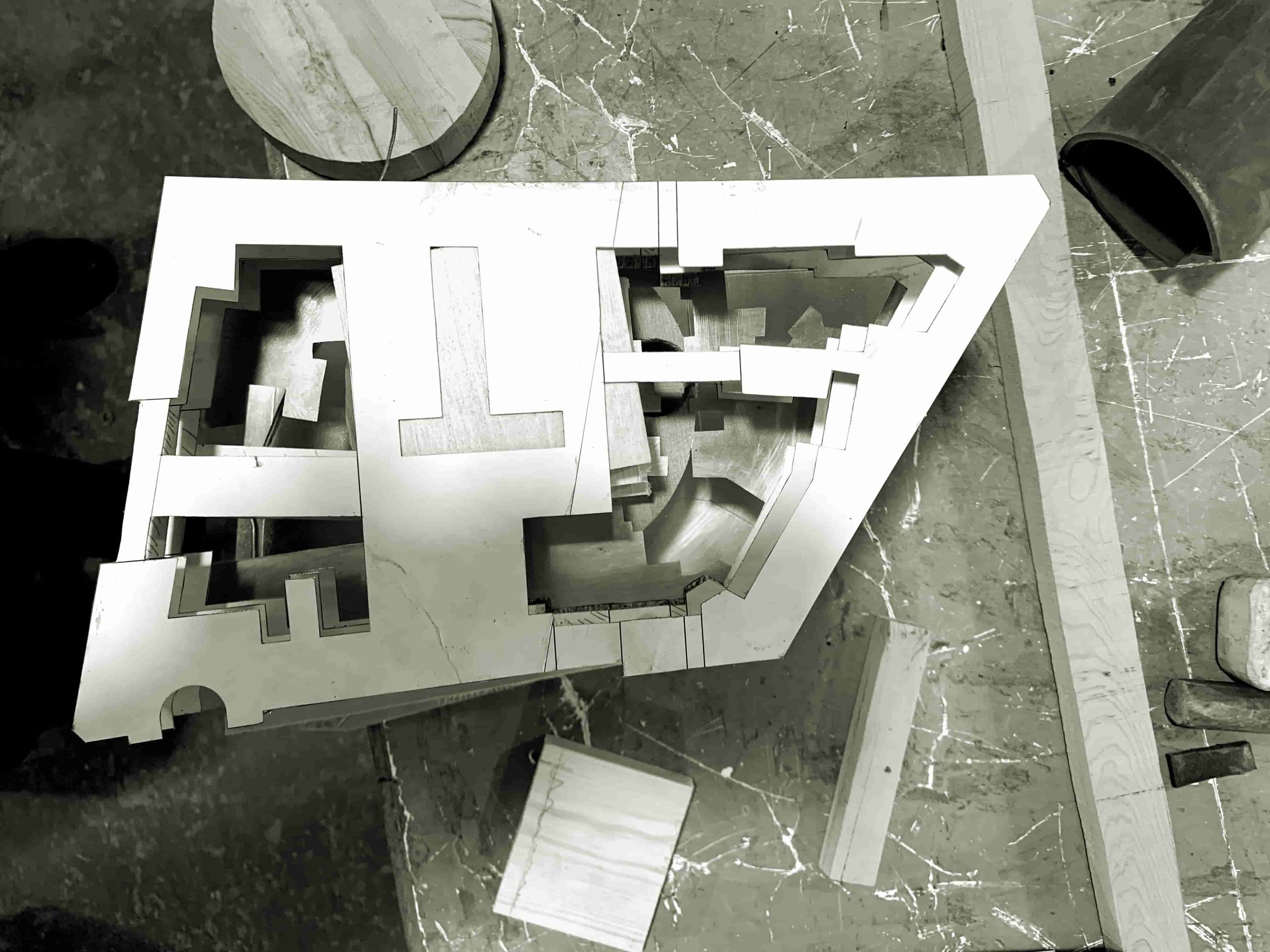

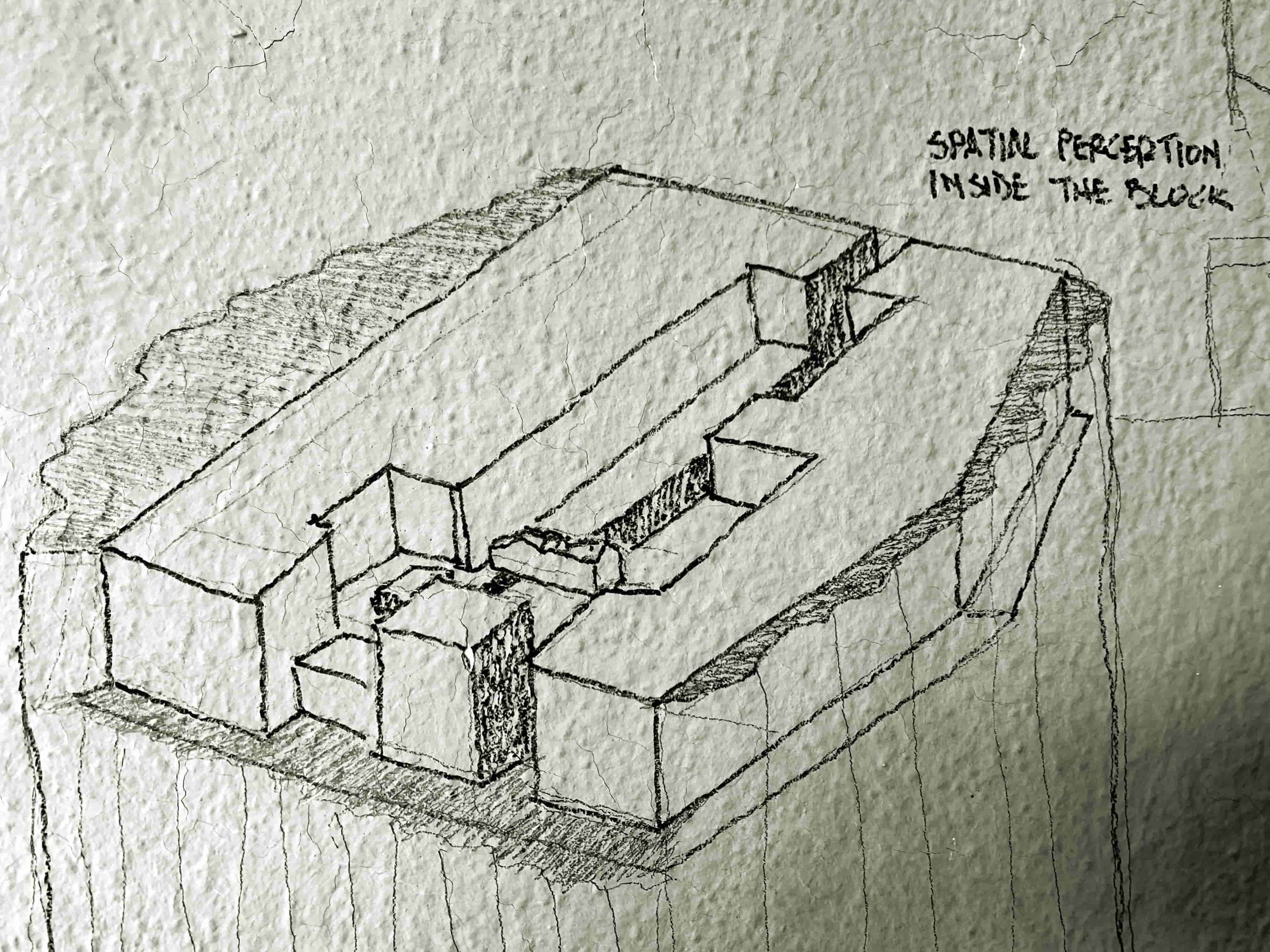

For me, the fundamental idea was to try to recover the use that this plot had before the beginning of the protectorate, that is to say, that of agricultural space within an oasis. In fact, our building was already an oasis of its own within an urban block. The axis proposed by Driss was important from an urban planning point of view, was going to be recognizable in the model since the two accesses to the heart of the urban block, from rue Mohammed el-Beqal and boulevard Abdelkrim el-Khattabi, were marked by the interruption of the facades. In the end, we agreed to make a model that would represent the massiveness of the block (almost entirely occupied by the new buildings) in relation to the interior space generated and the existence of our building.

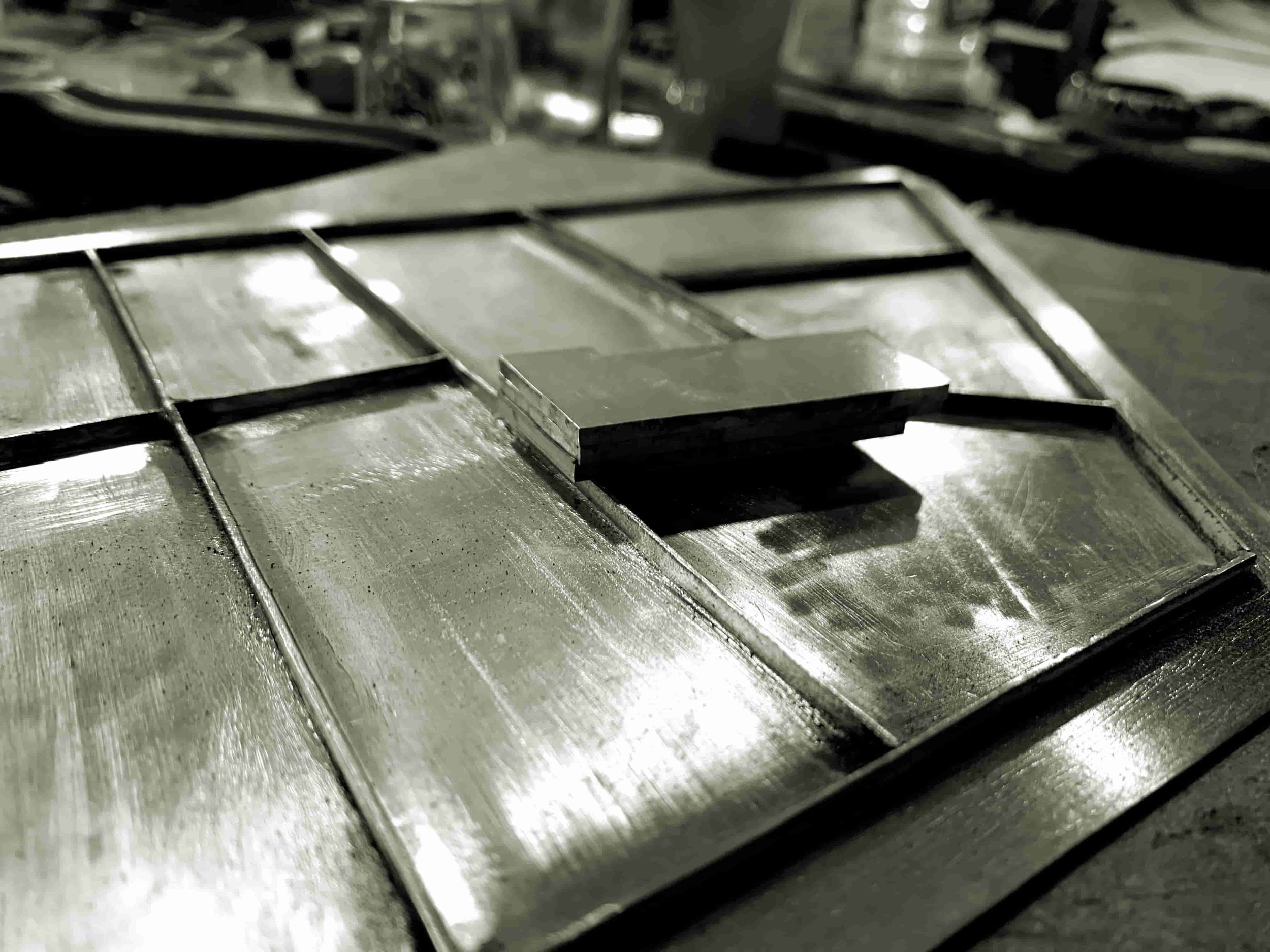

Then we had to decide on the material to use, cardboard-foam, 3d printing, wood... But if the starting point was to work with the craftsmen, it was clear that we had to make the wooden model, taking into account the technical level and the experience of the craftsmen. When we started to think about how we were going to make the model, we realized that we had to change our mindset, because we naturally took for granted the decisions that led us to a "traditional" type model from an architectural point of view. Sometimes we had to go back to the original premises without preconceived images of what the outcome should be.

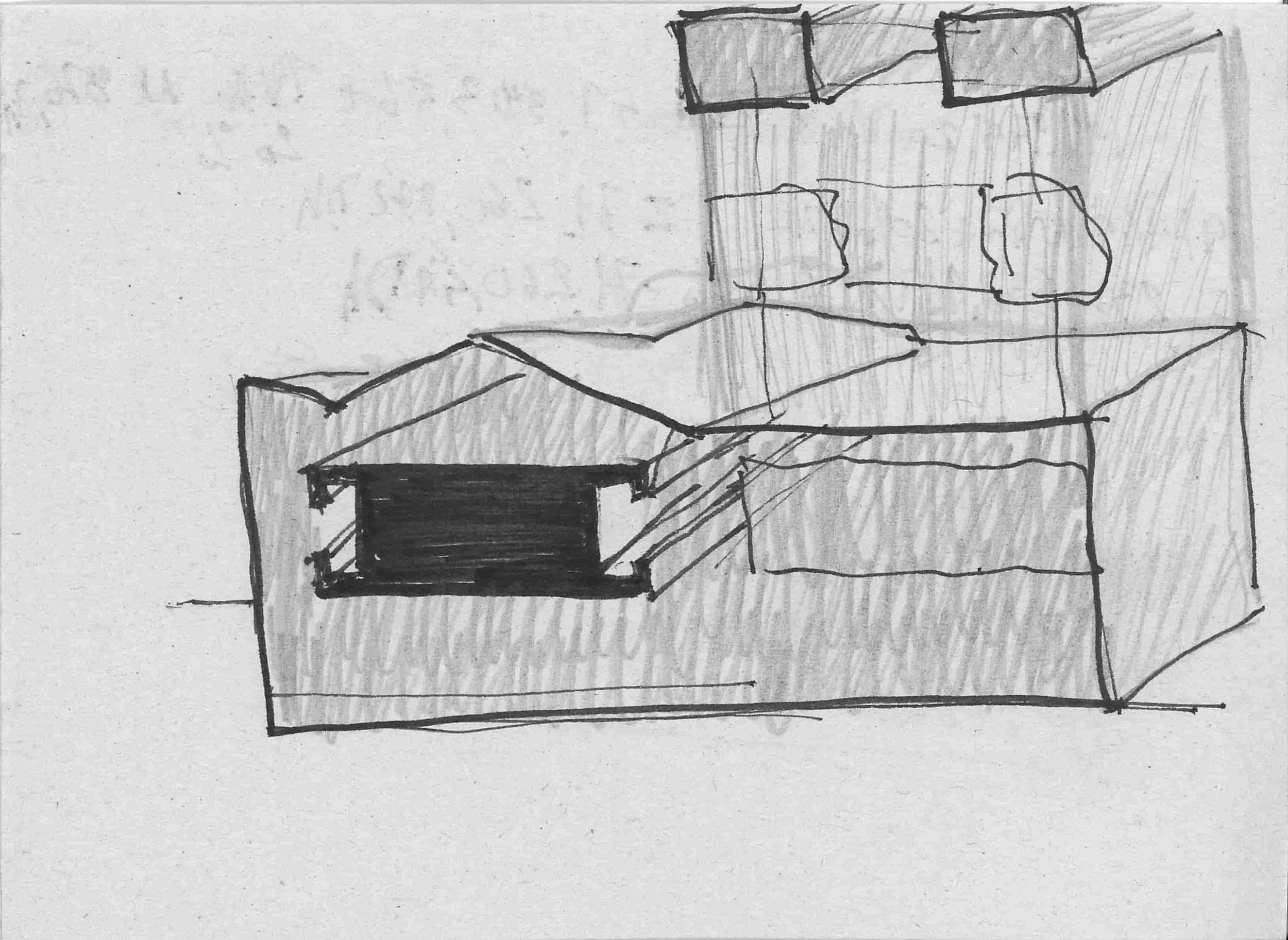

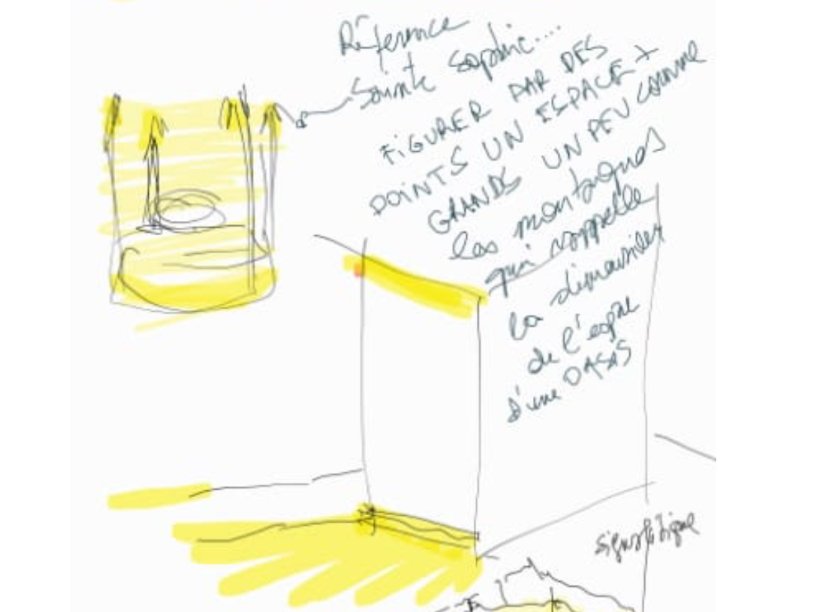

With the first sketches we tried to test masses that would represent the volumes perceptible from the roof of our building, without taking into account the difference in height of the buildings or the existence of windows, balconies or terraces, only solid volumes.

For the second phase, we drew this representation of the urban block in 3D, with the main axe, in order to test the scales and dimensions of the model.

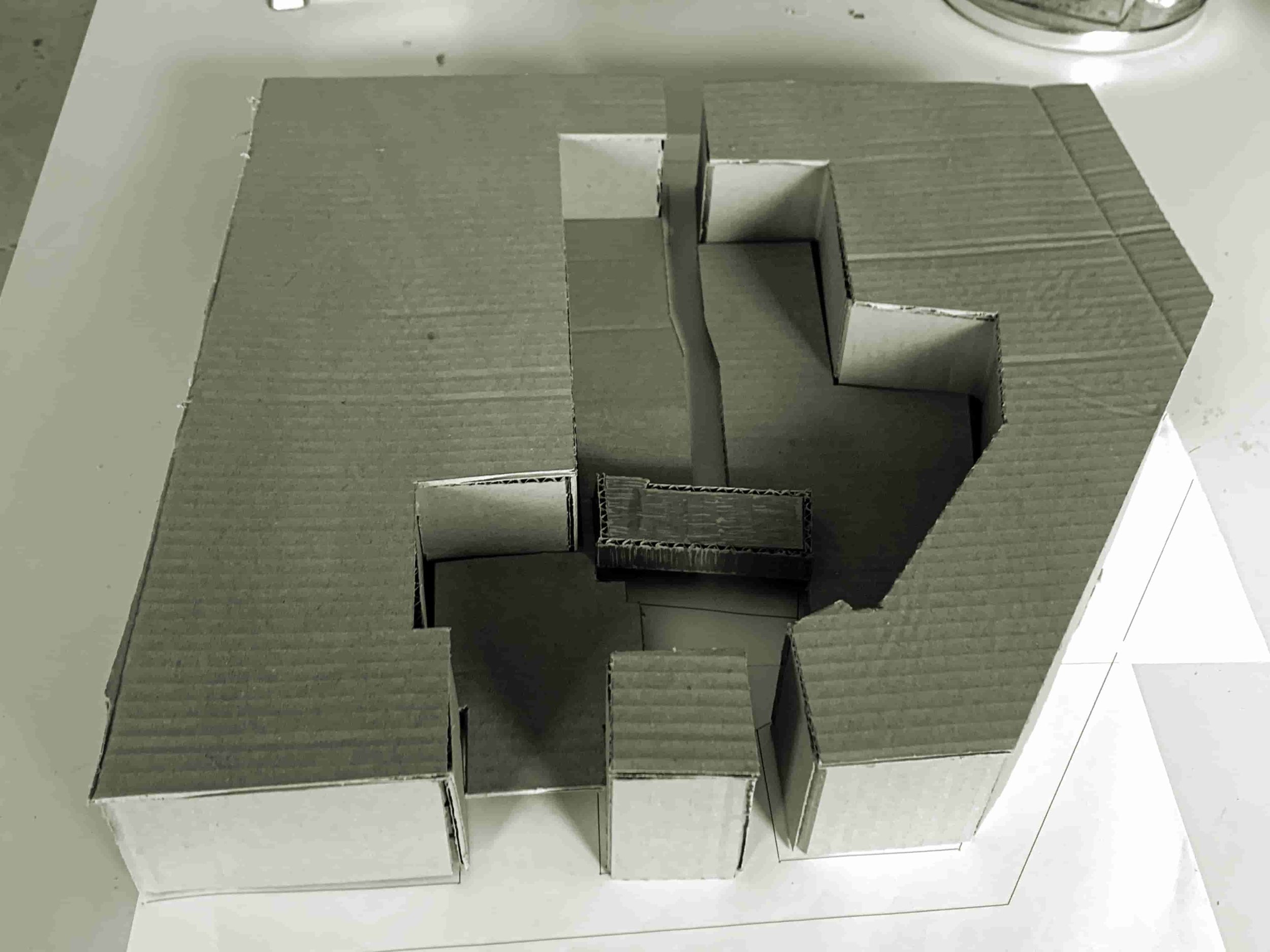

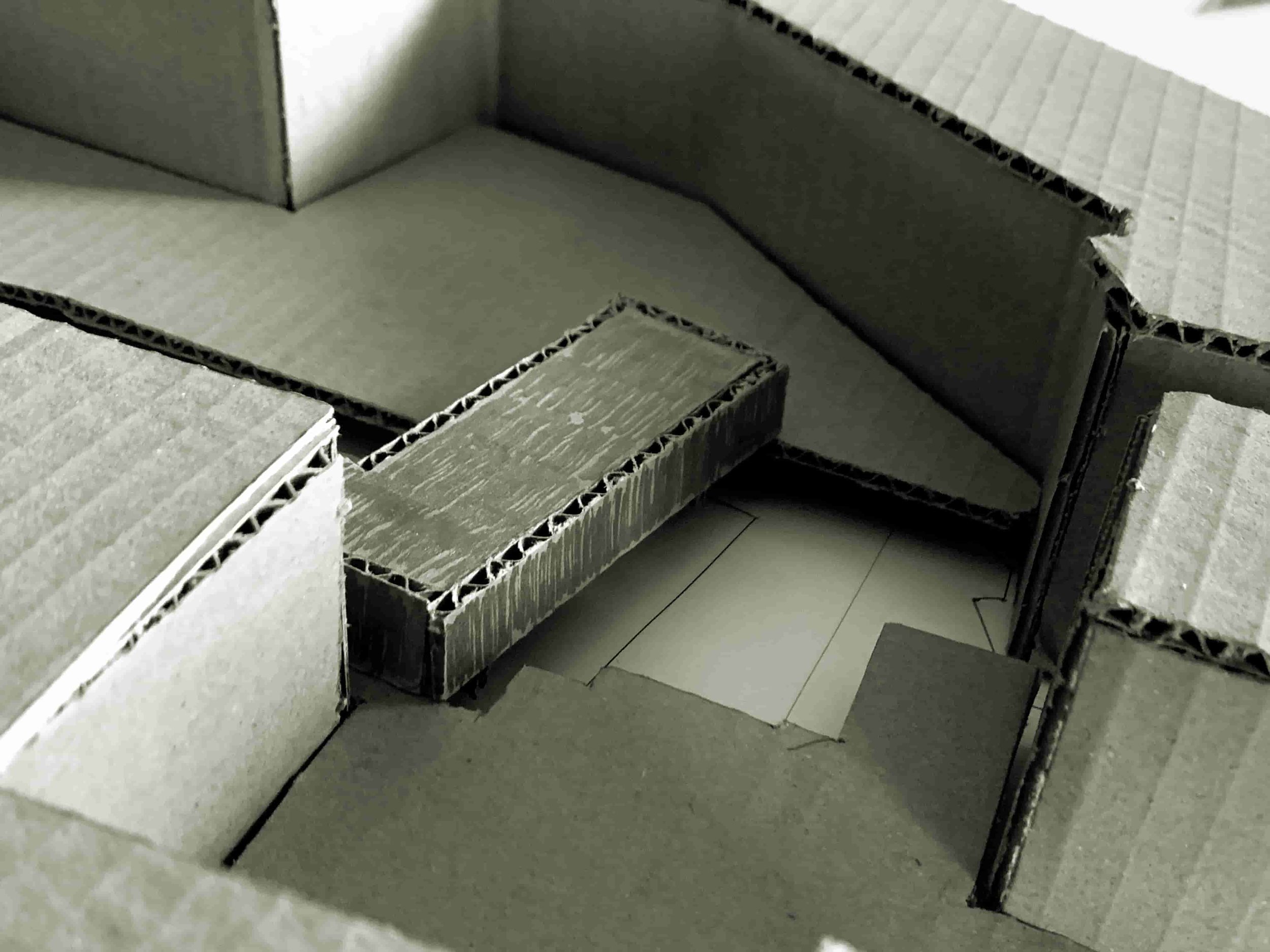

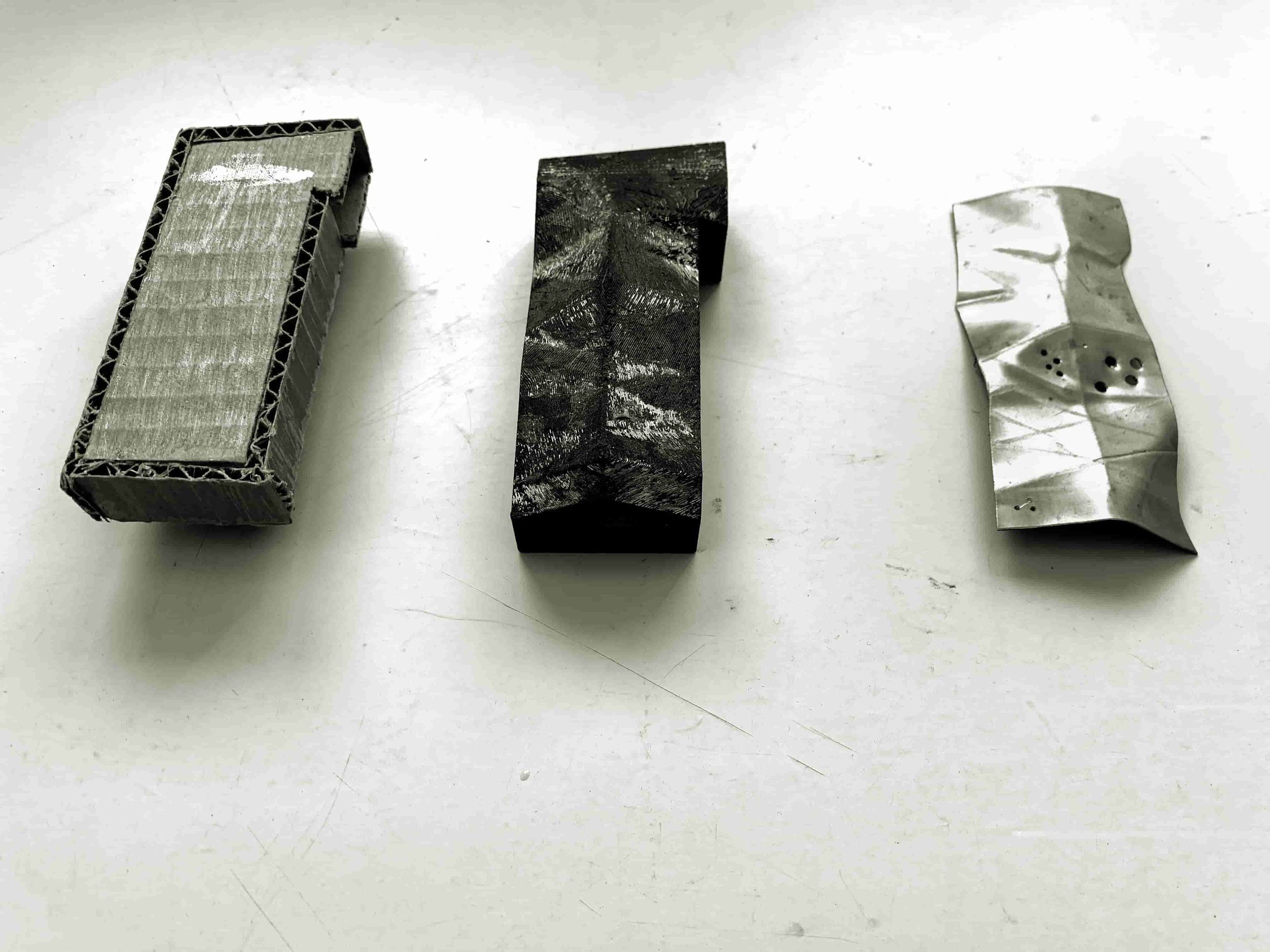

Then we made a cardboard model to check the scales again and see the relevance of treating our building and our plot differently.

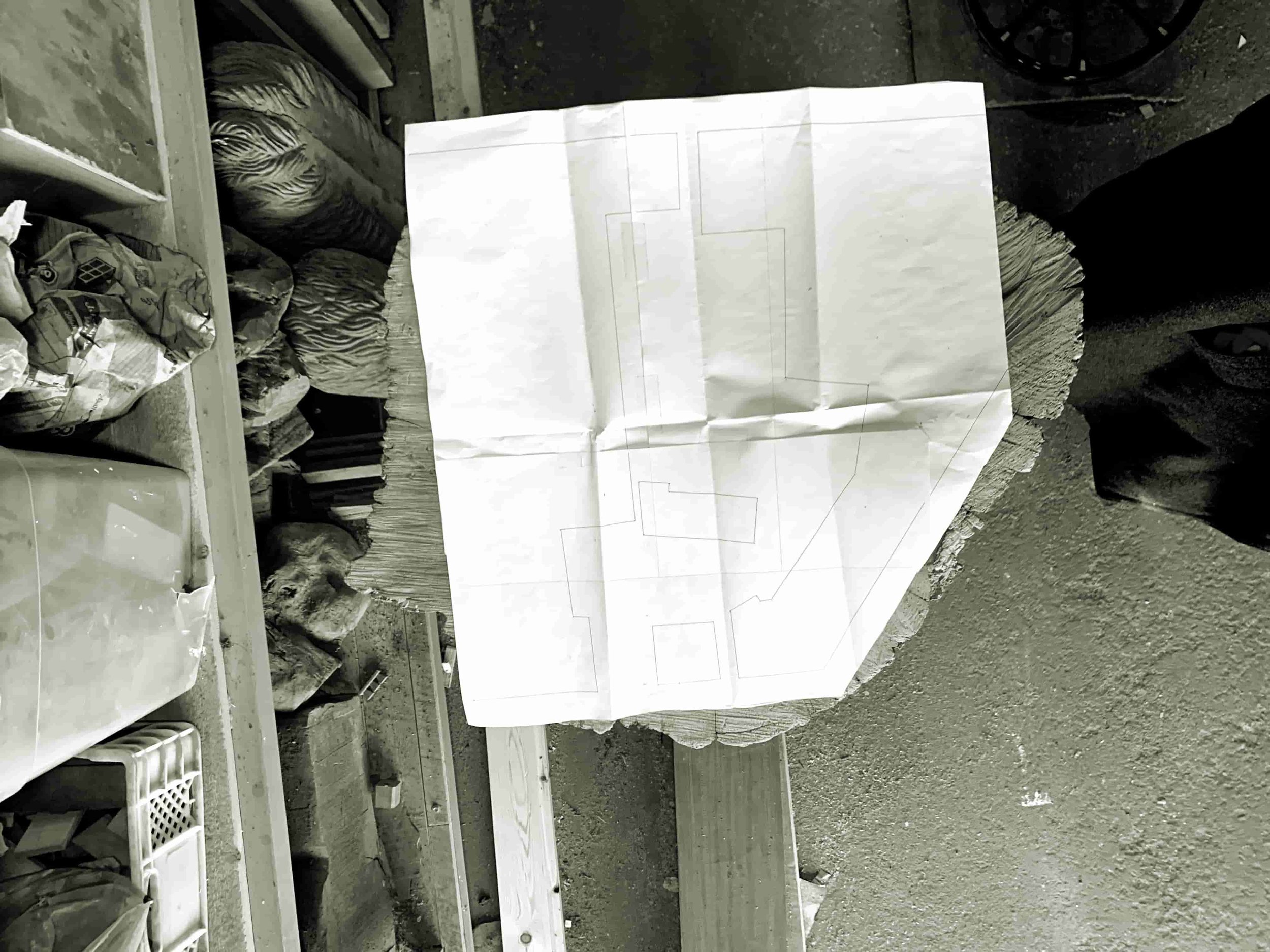

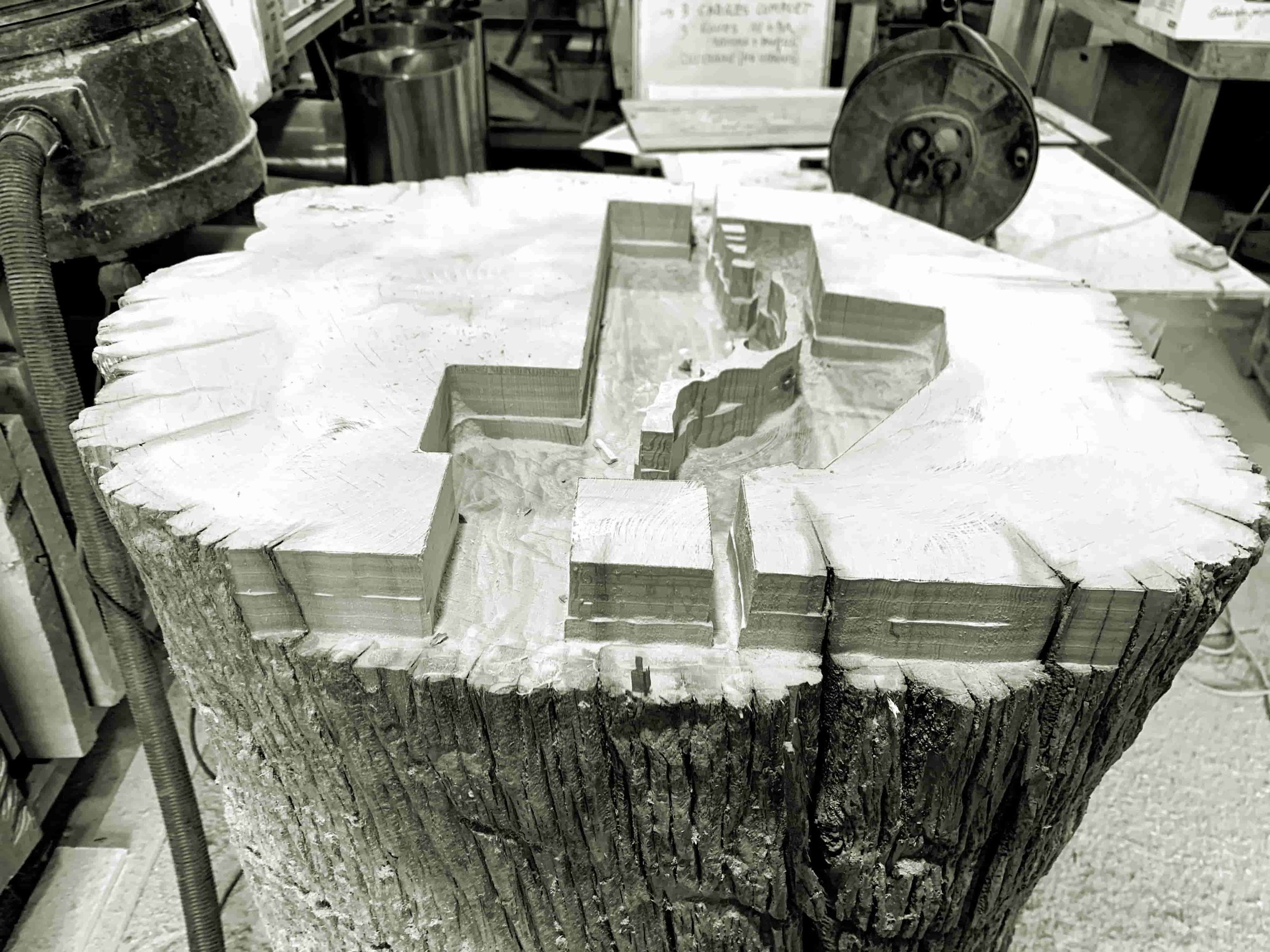

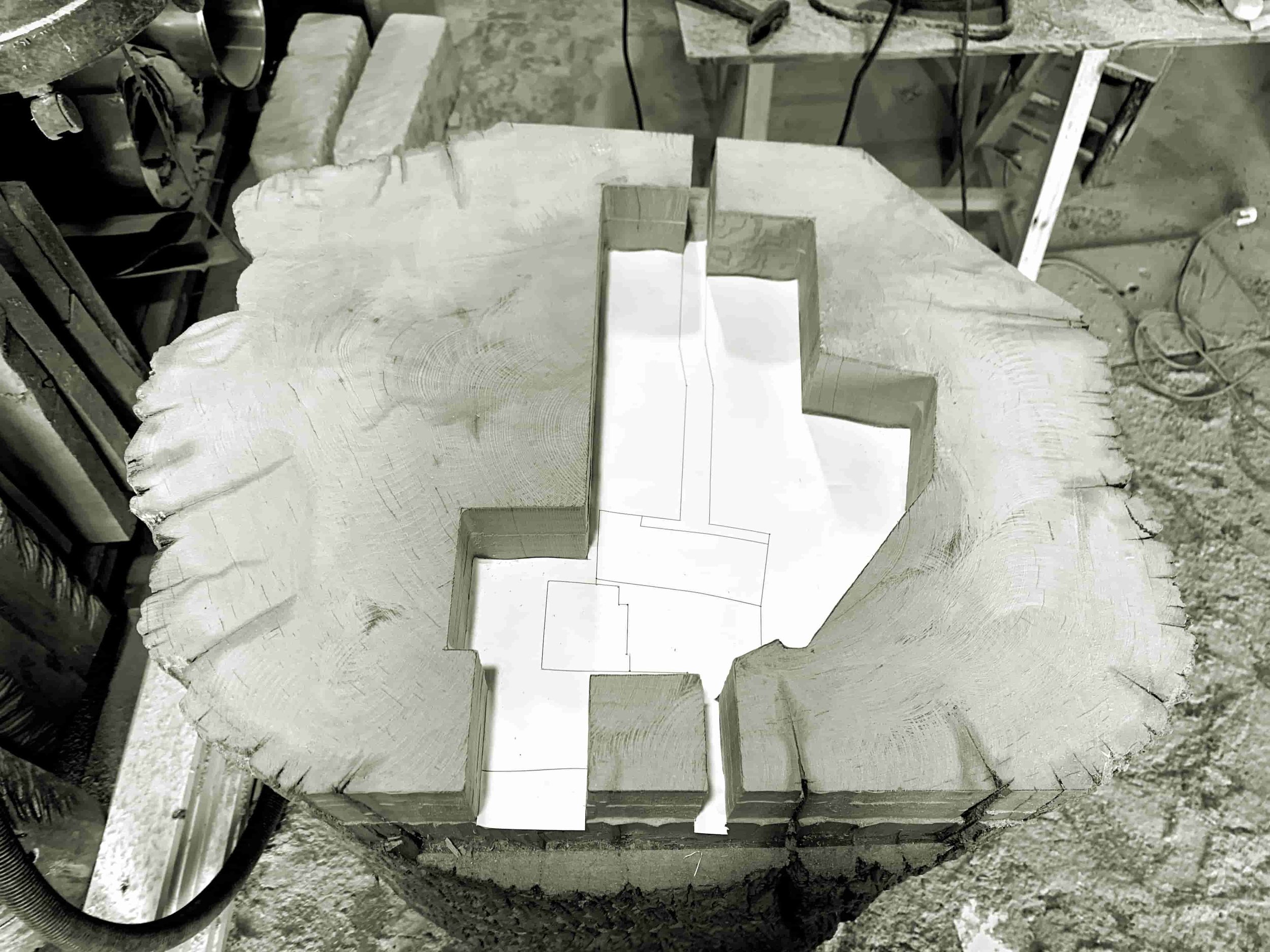

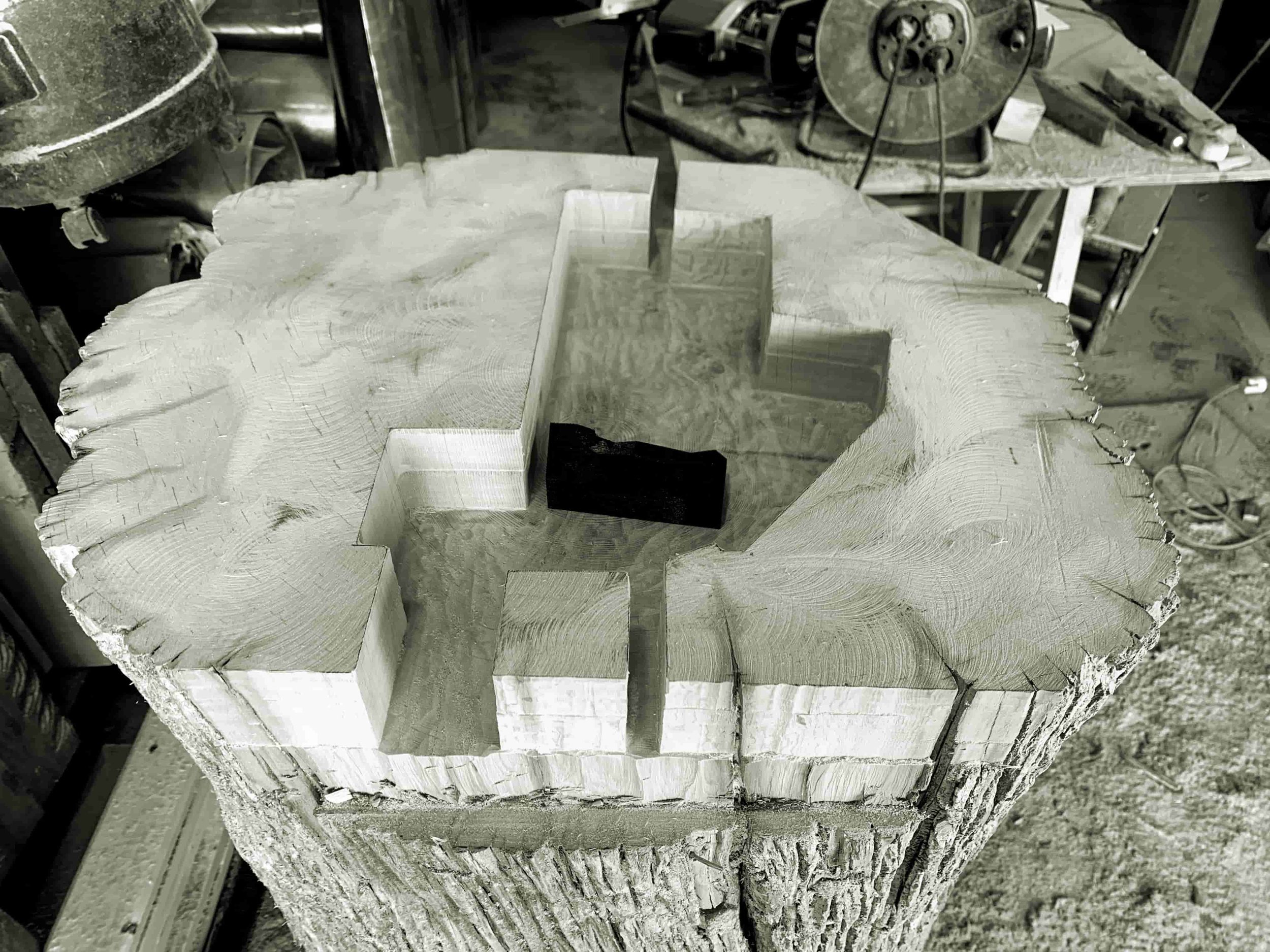

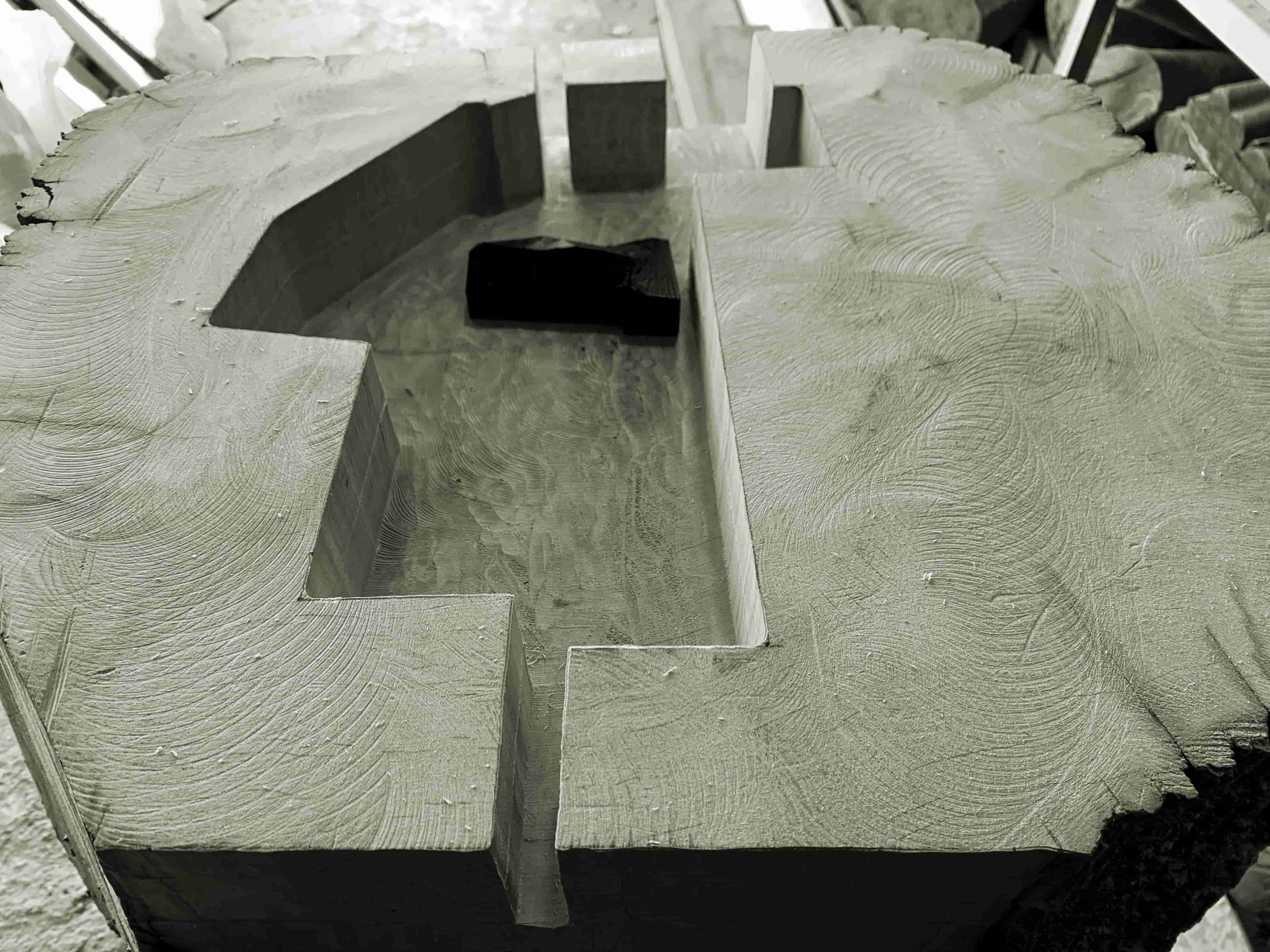

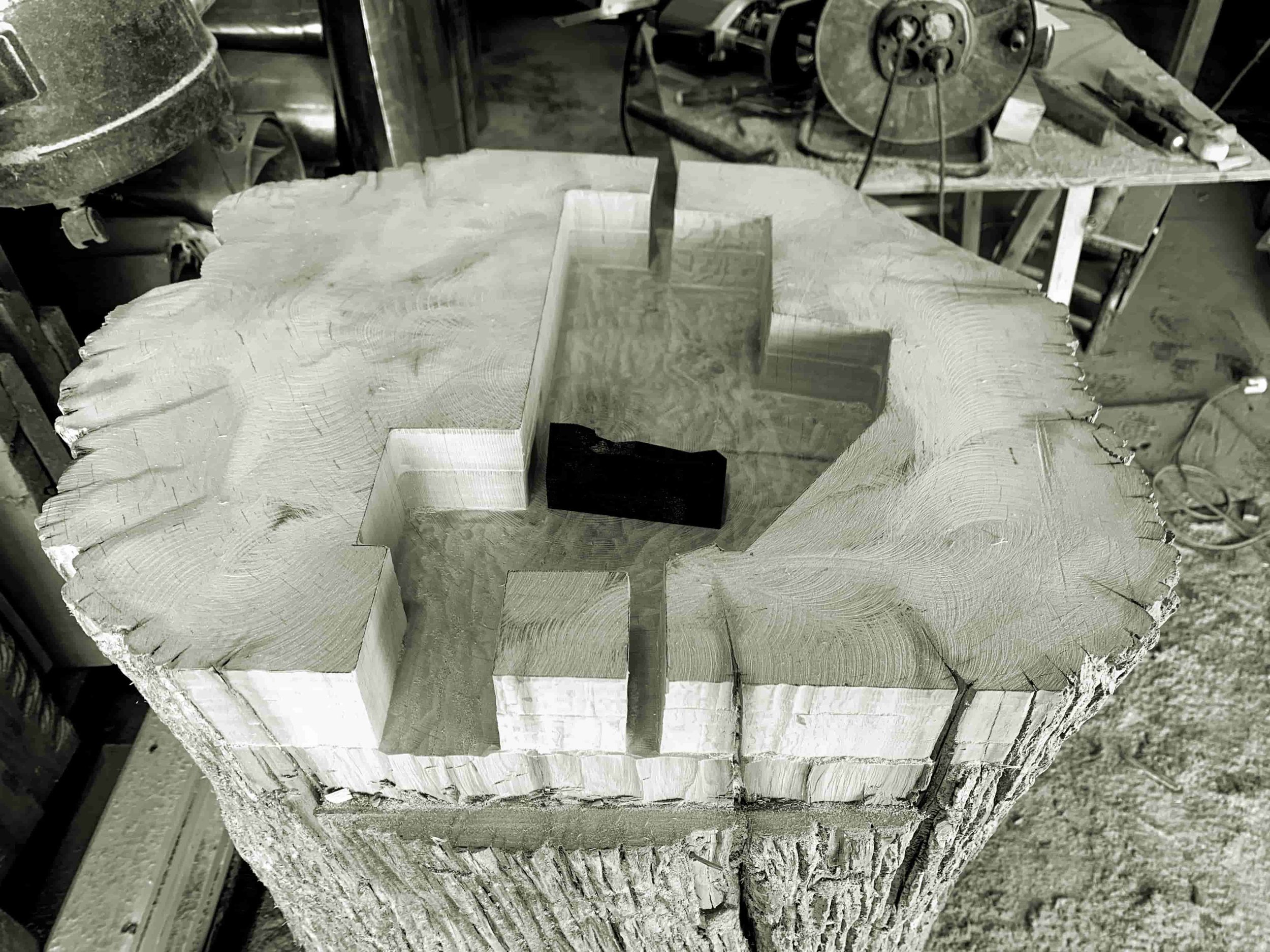

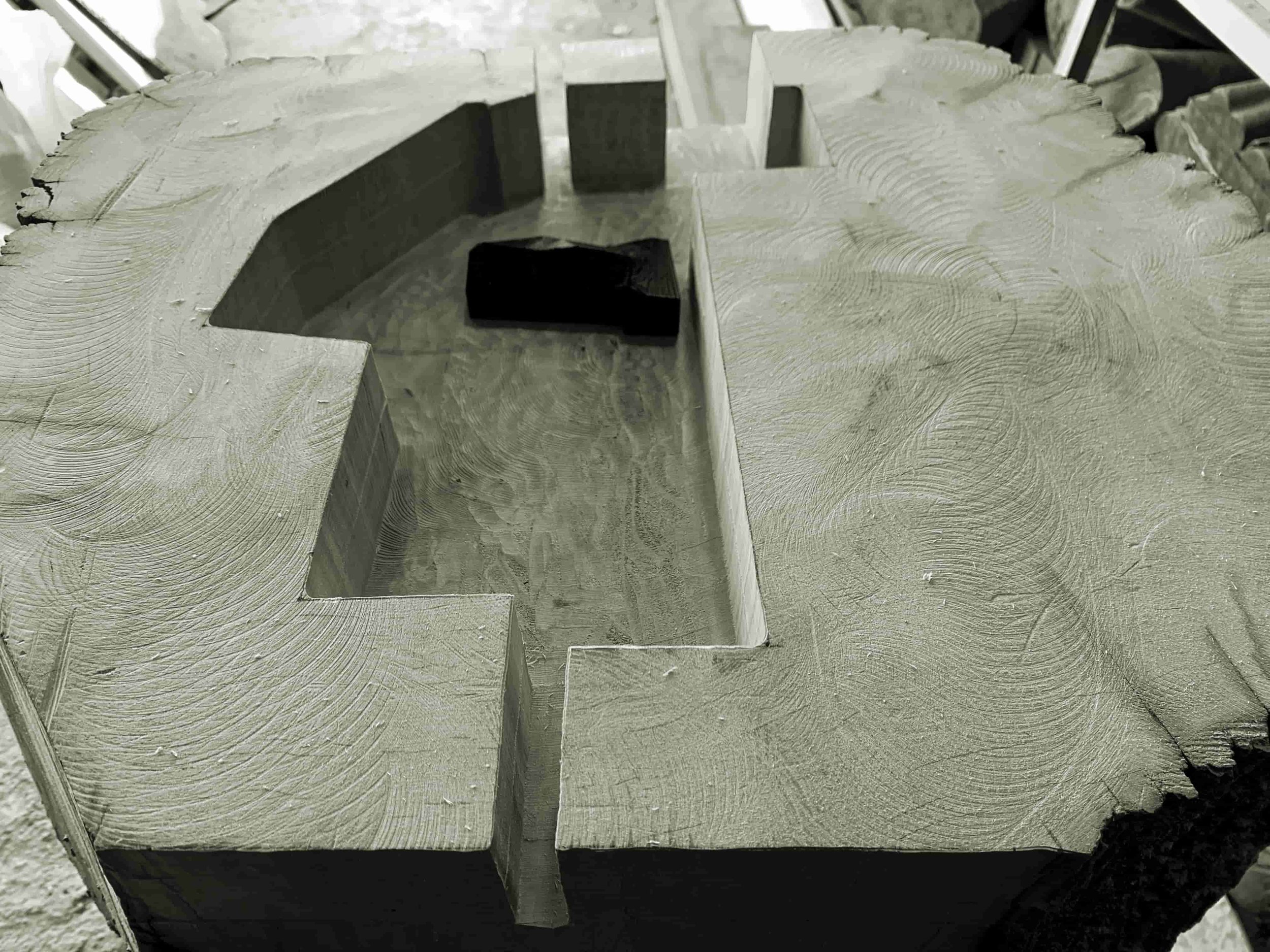

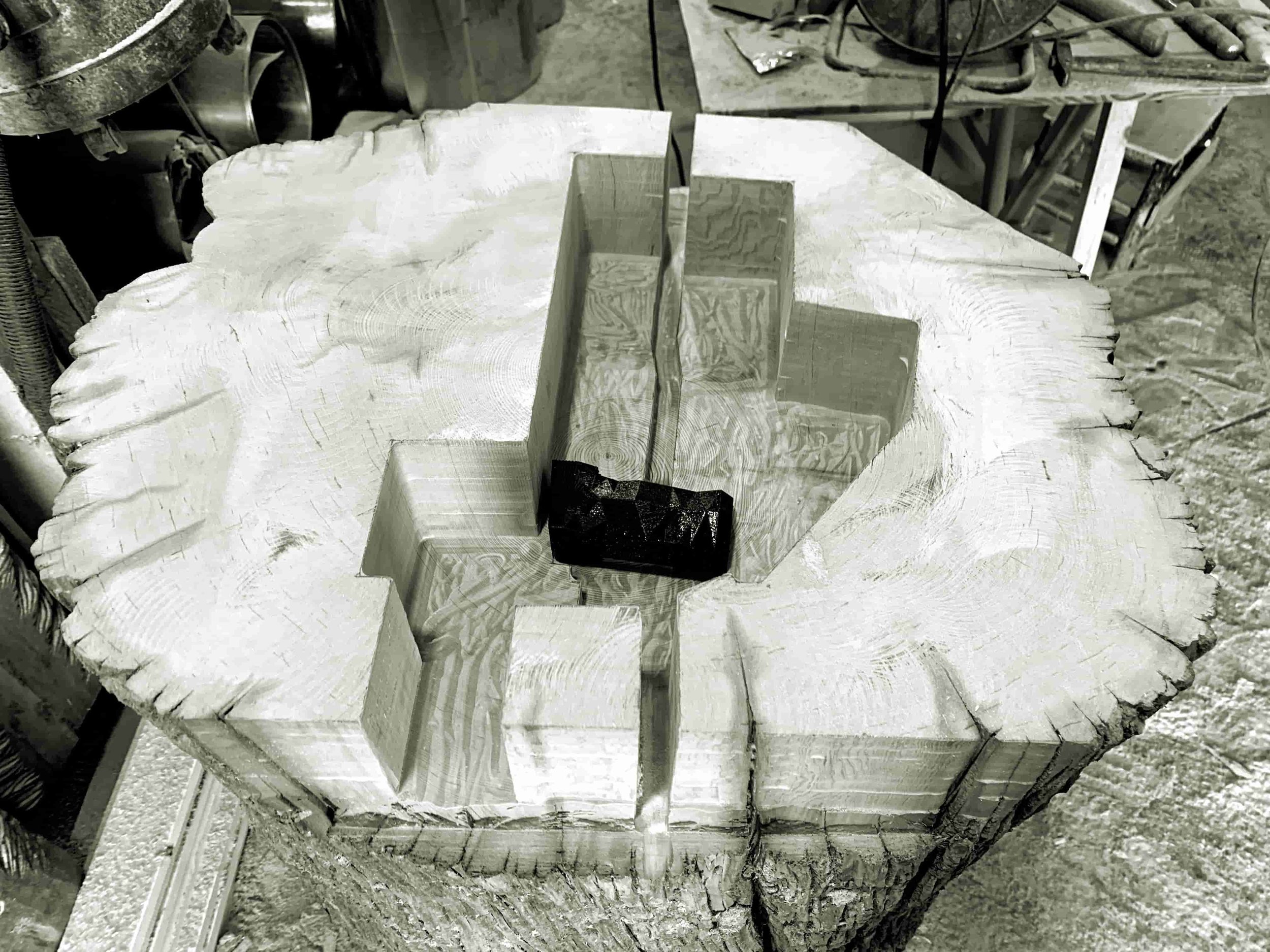

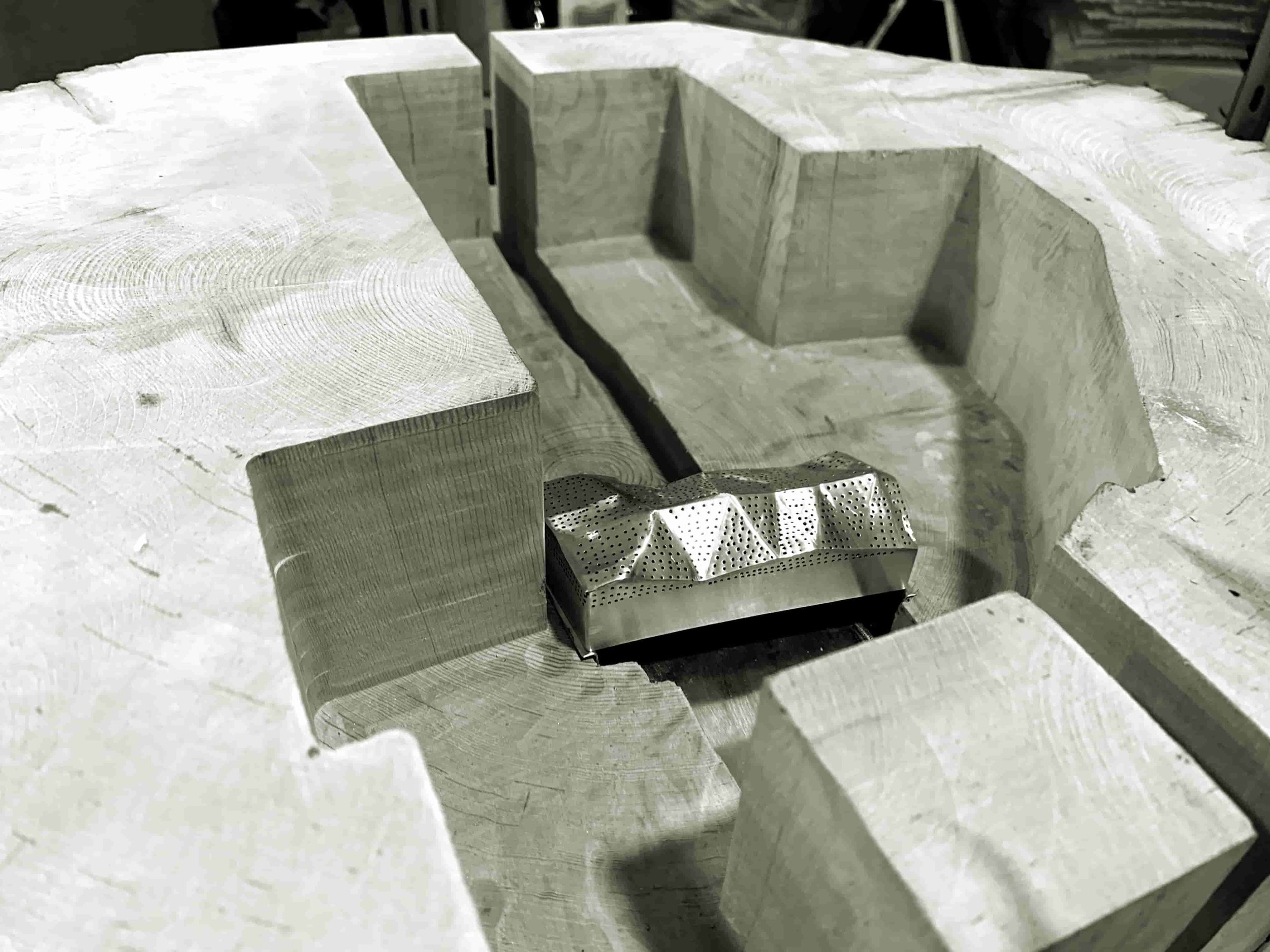

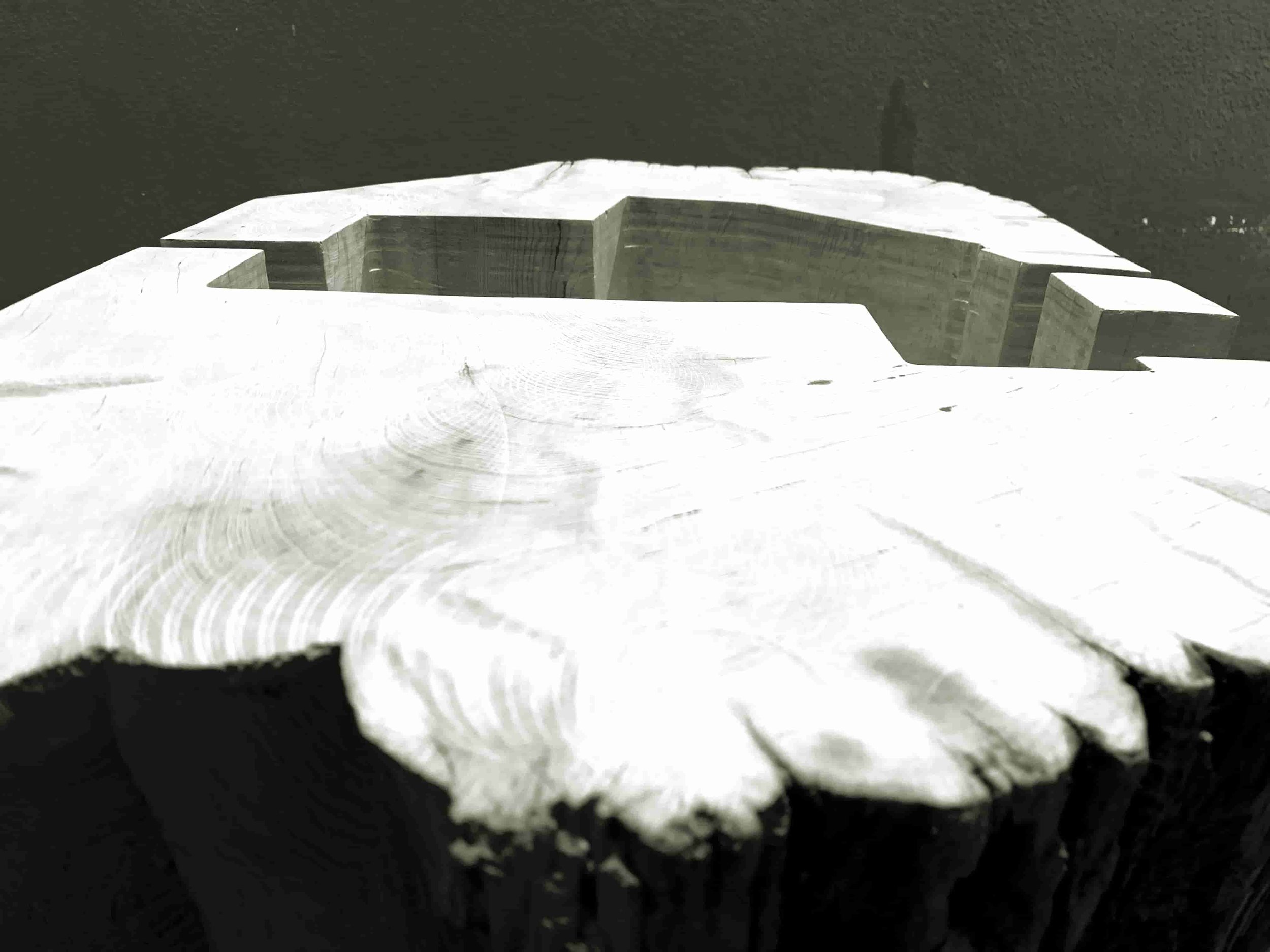

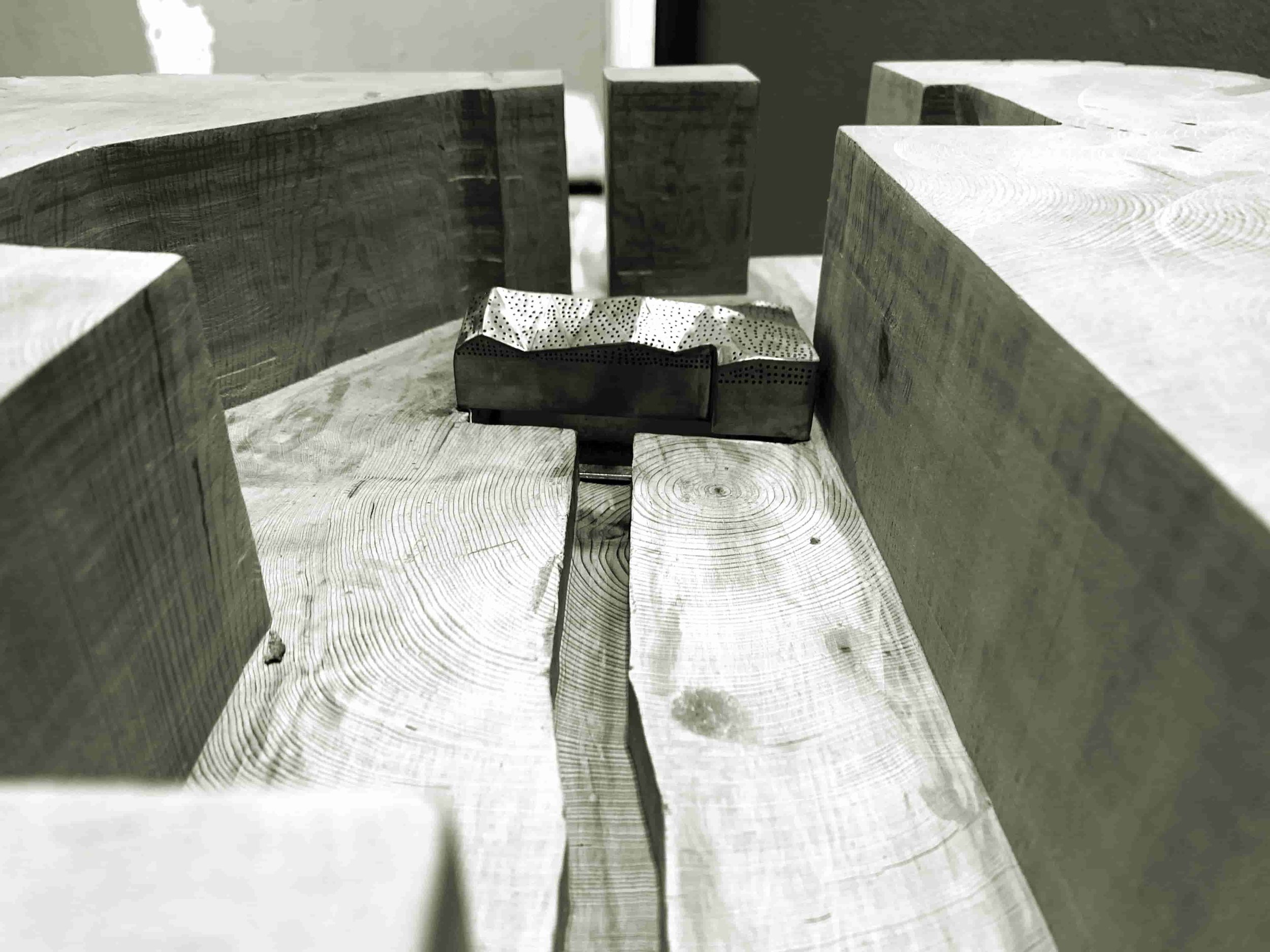

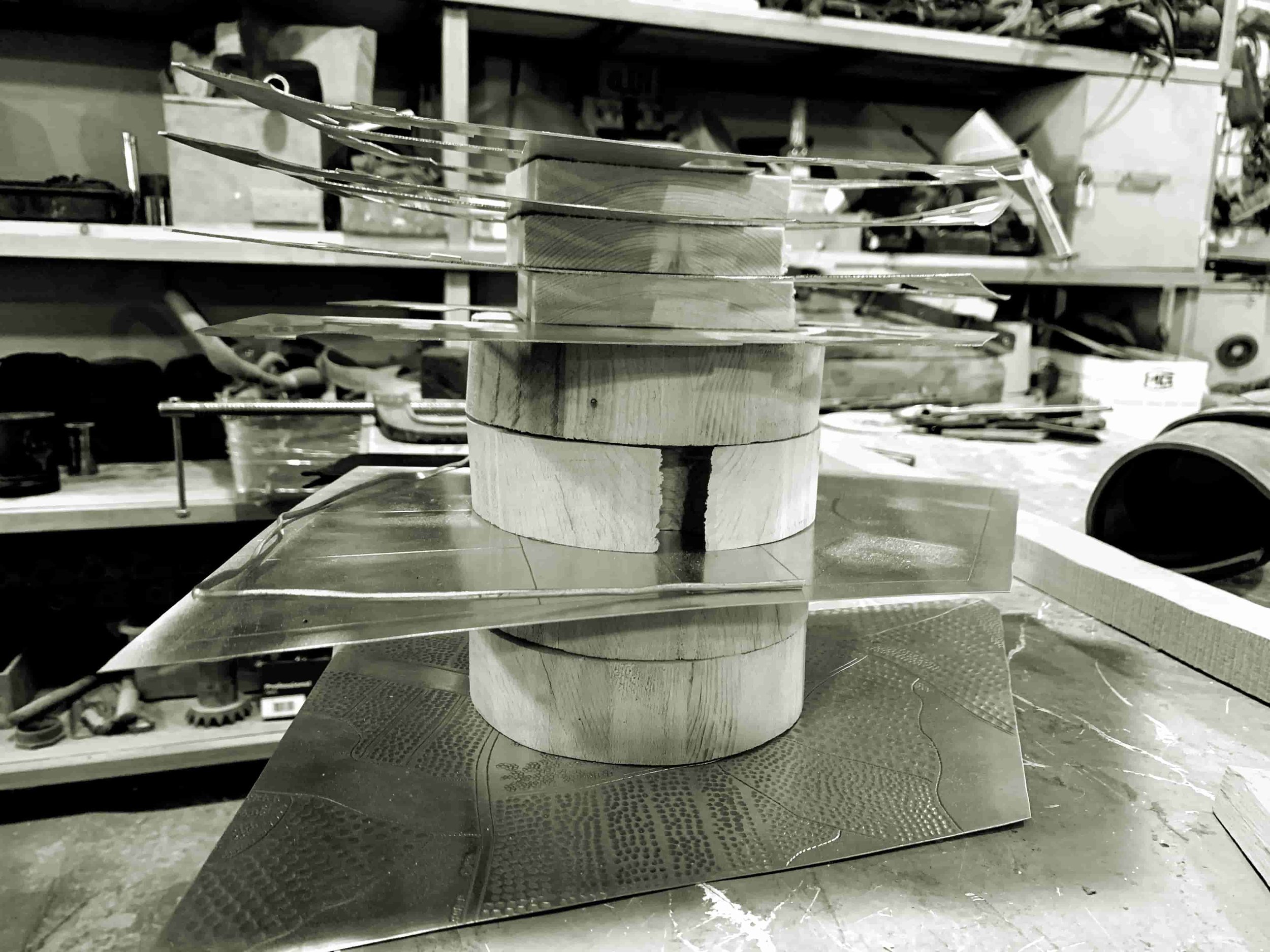

Thanks to the cardboard model we knew that we could not simply build its wooden volumes and place them on a one centimeter thick board, we had to start from a wooden block and empty the interior, taking advantage of the know-how of the wooden craftsmen of Fenduq. With the final scale plans and photos of the wooden model, we thought that was enough information to move on to “manufacturing” in the Fenduq workshops in Sidi Moussa, but we still had to find a proper wooden block. After explaining to Eric what we wanted to do, he told us that they could find a piece of cedar trunk with a diameter of 60-70 cm but we had to decide the height. Compared to the existing buildings we testes with cardboard model, with 12 cm was sufficient but it was necessary to add even more, in order to really show that it was a piece of cedar trunk that has been hollowed out. Finally we proposed 70 cm. Two days later, we received at the workshop a delivery from Ifrane, a cedar trunk 70 cm in diameter and 120 cm in height. Accustomed to the dimensions of architectural models, we thought that already having 70 cm in height was something magnificent, but when Eric told us why we did not keep the whole trunk in order to avoid looking for a base to put the model on, we realised how approaches between artists and architects could be different.

Before starting the work on the trunk we asked the opinion of Dragon (Abdelkhader) and Abdelghafour about what we proposed and the procedure, they told us it was easy and quick to do.

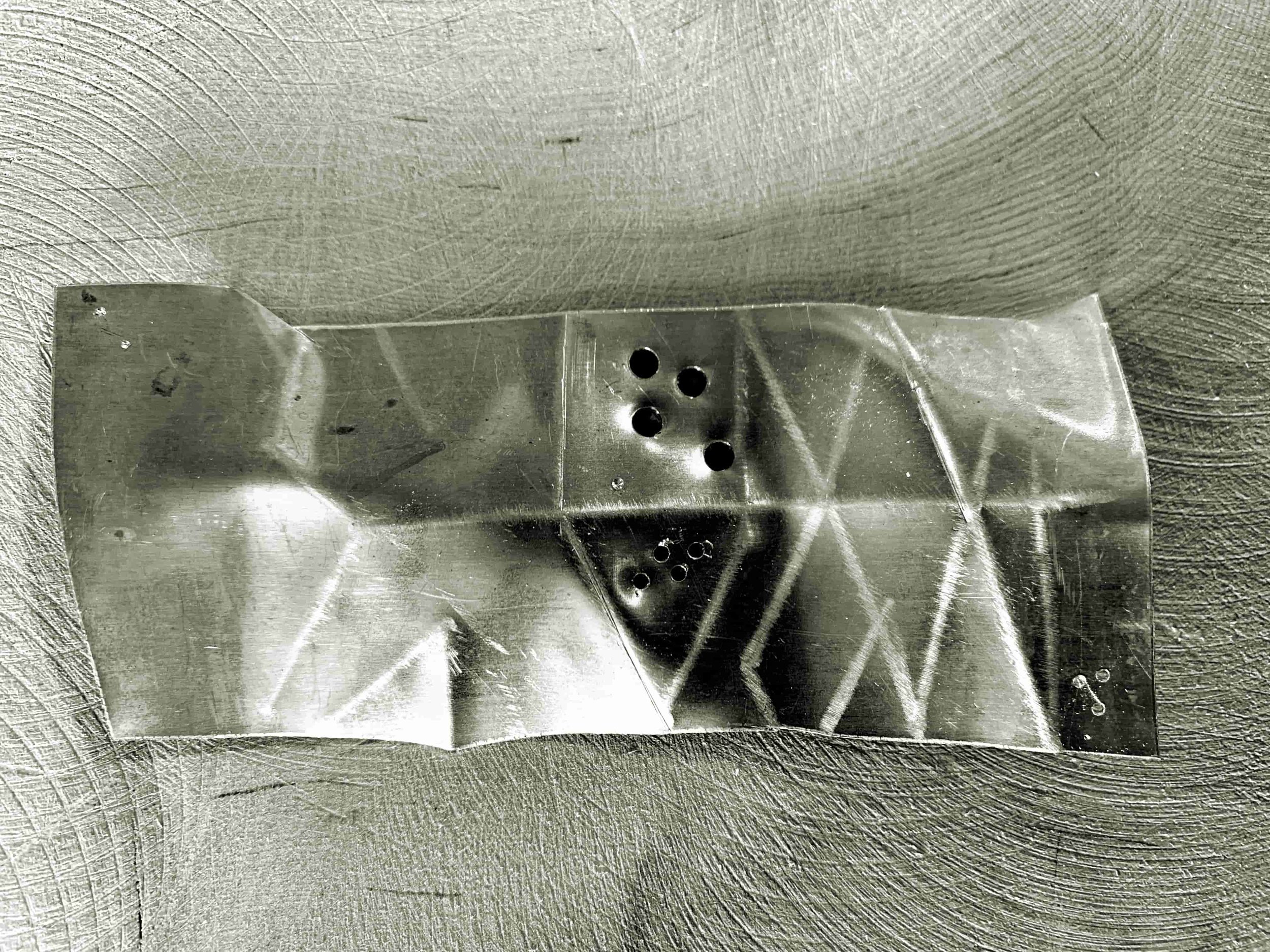

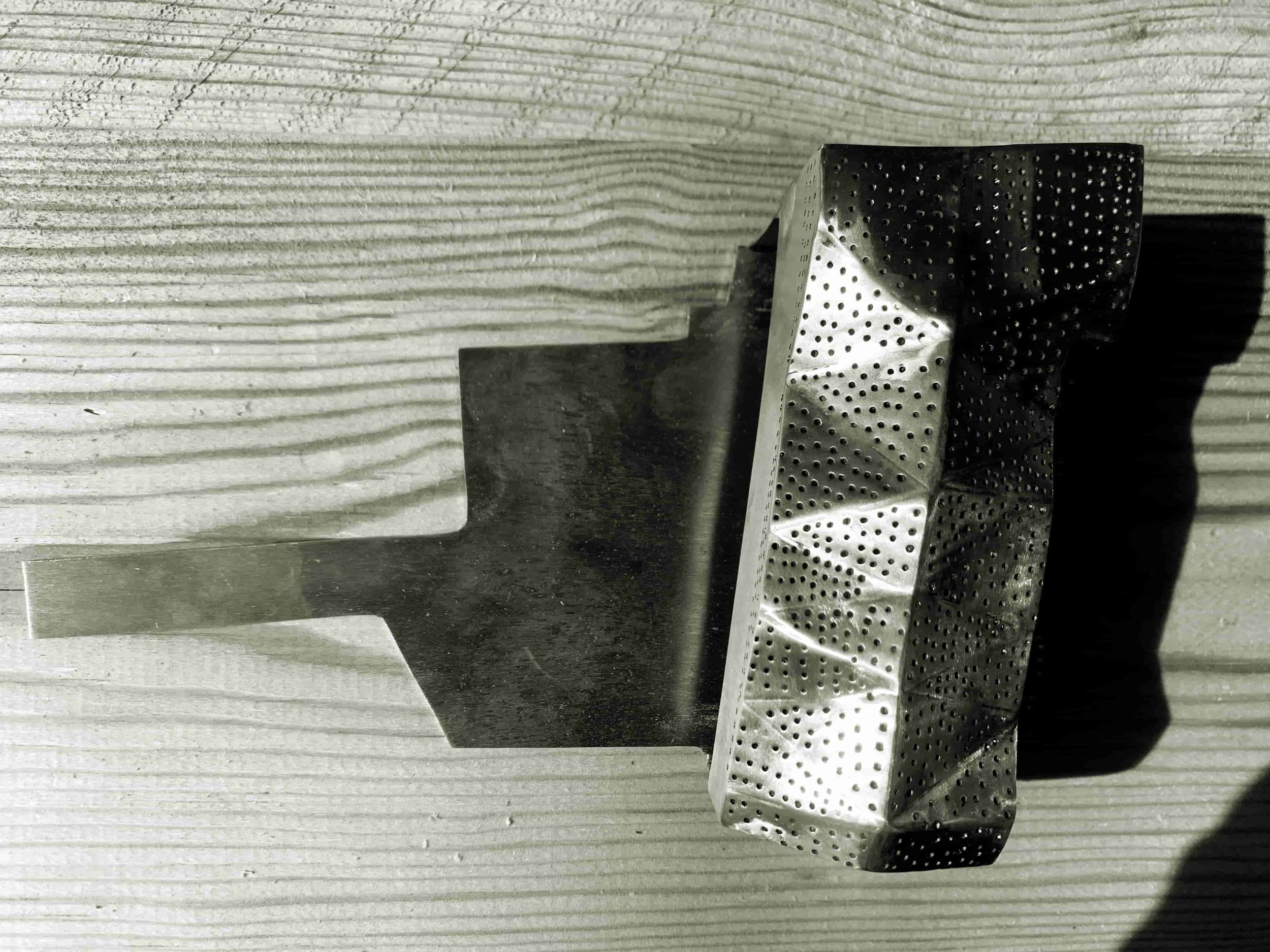

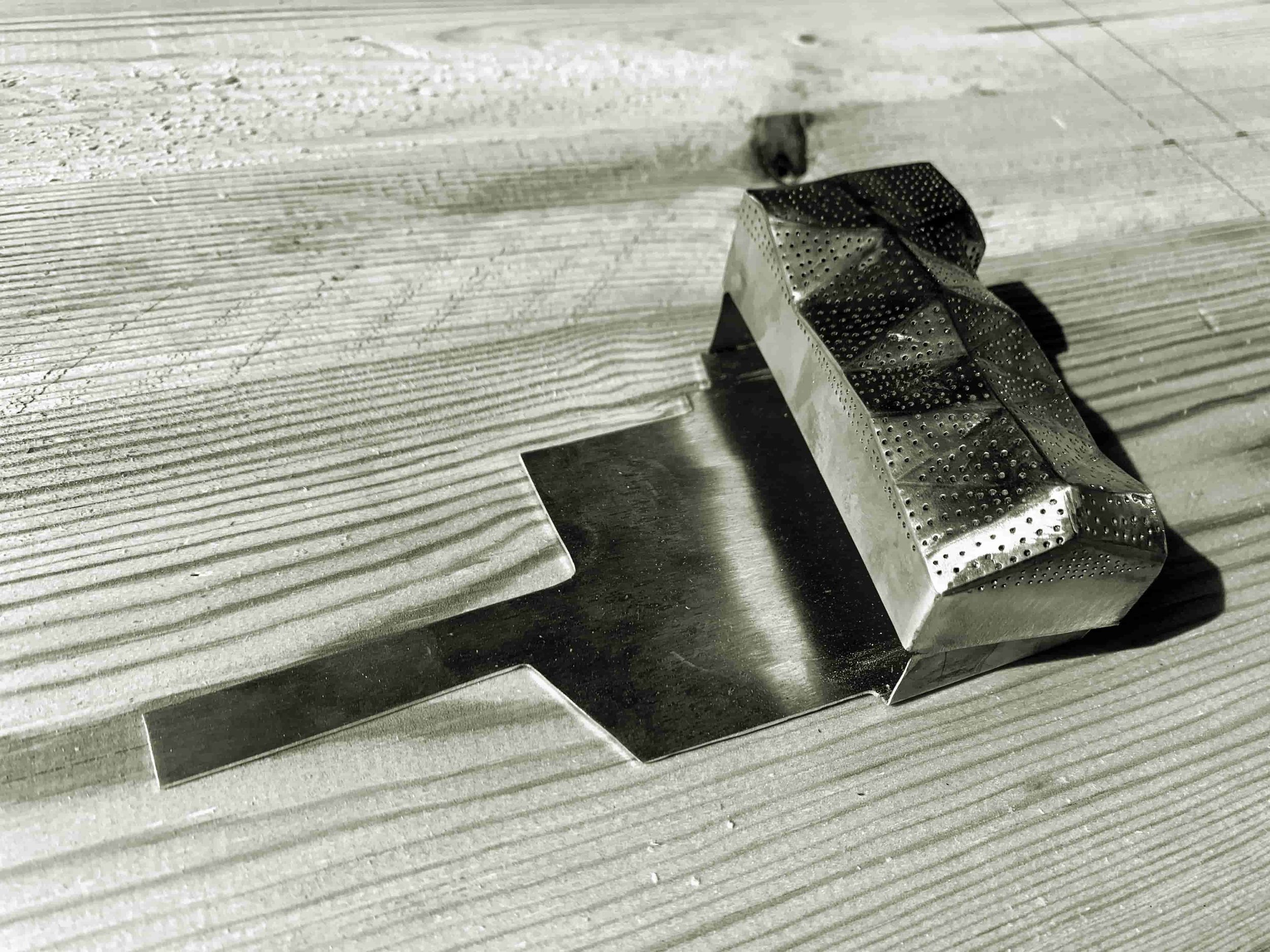

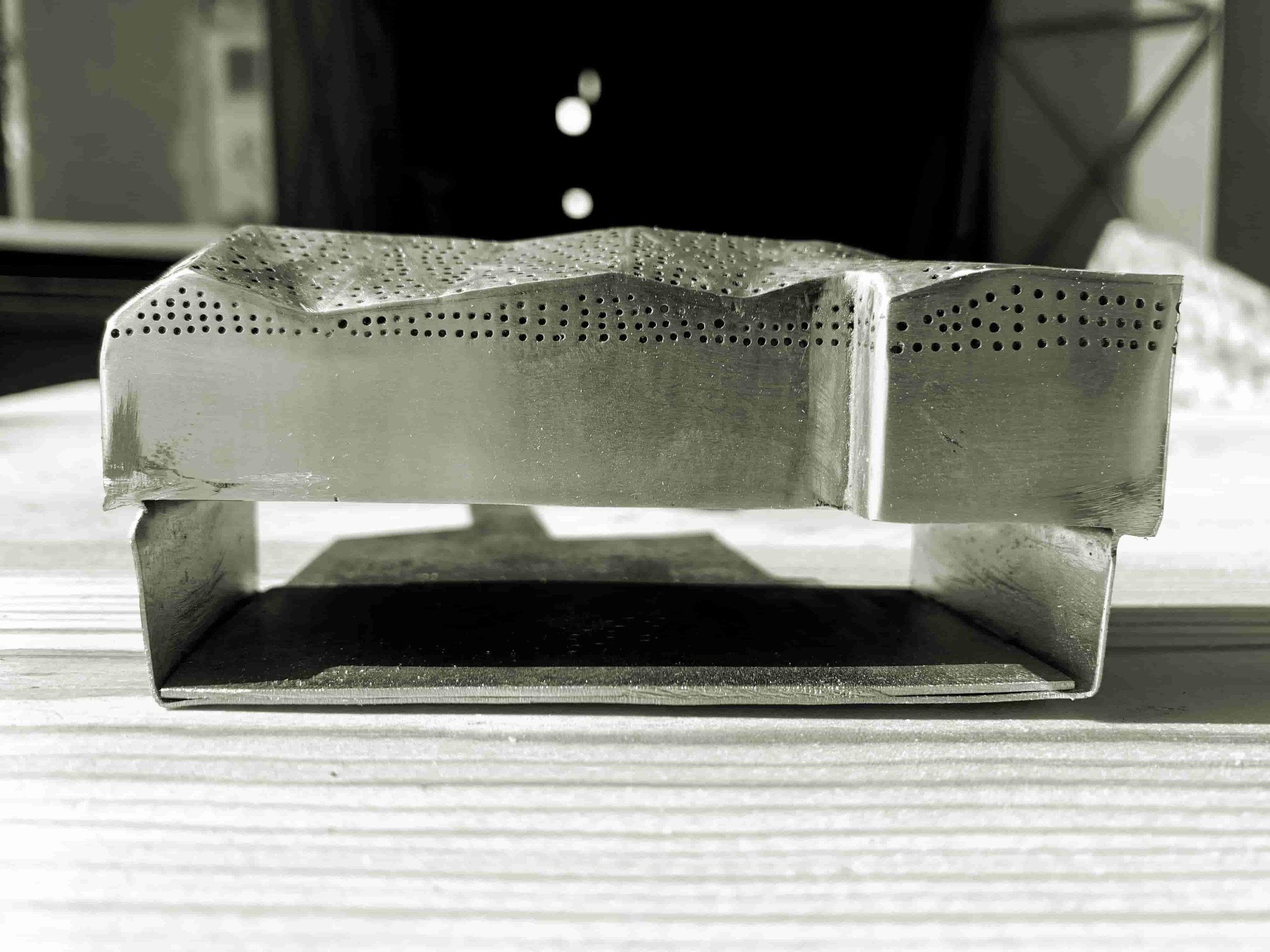

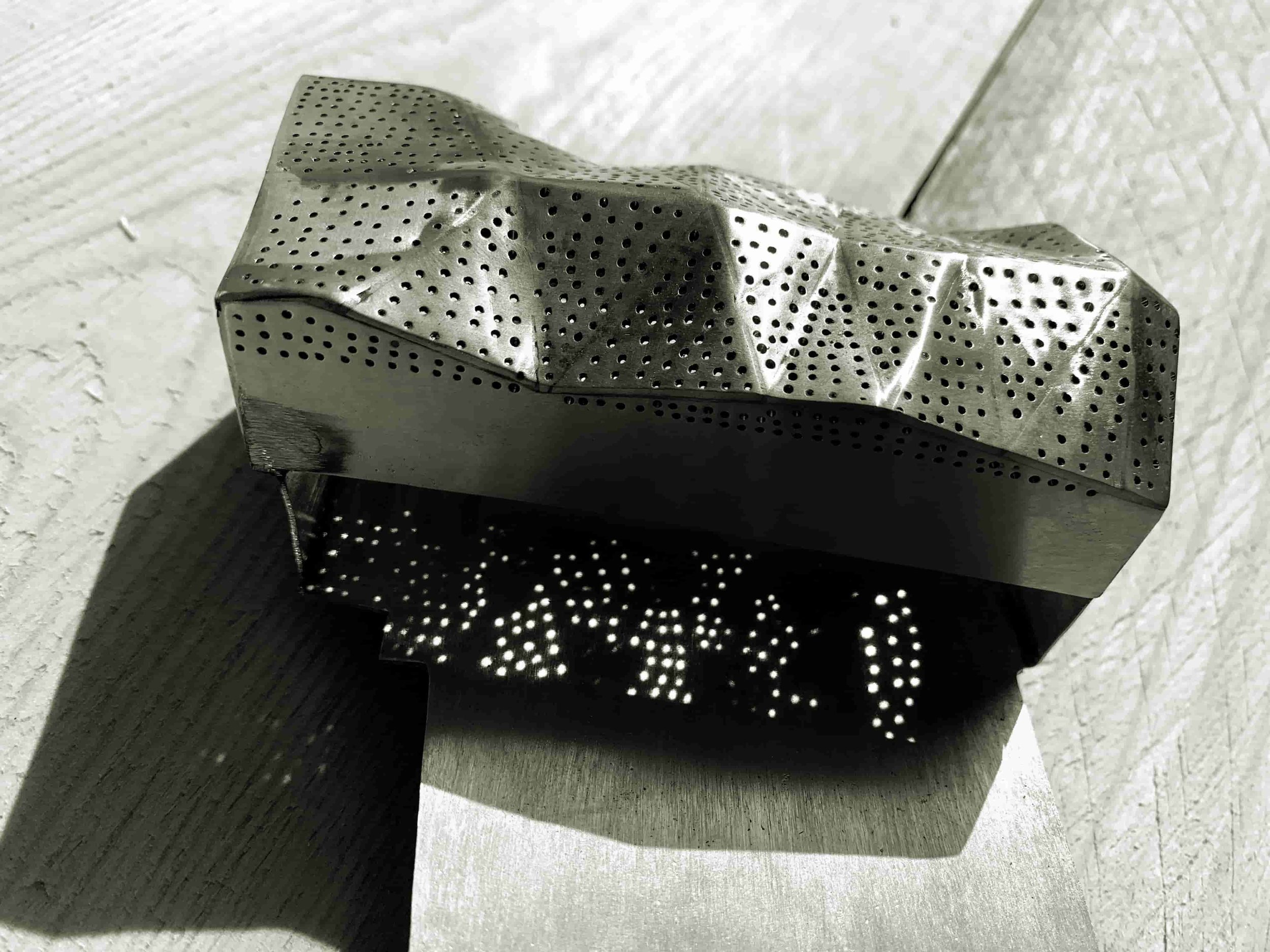

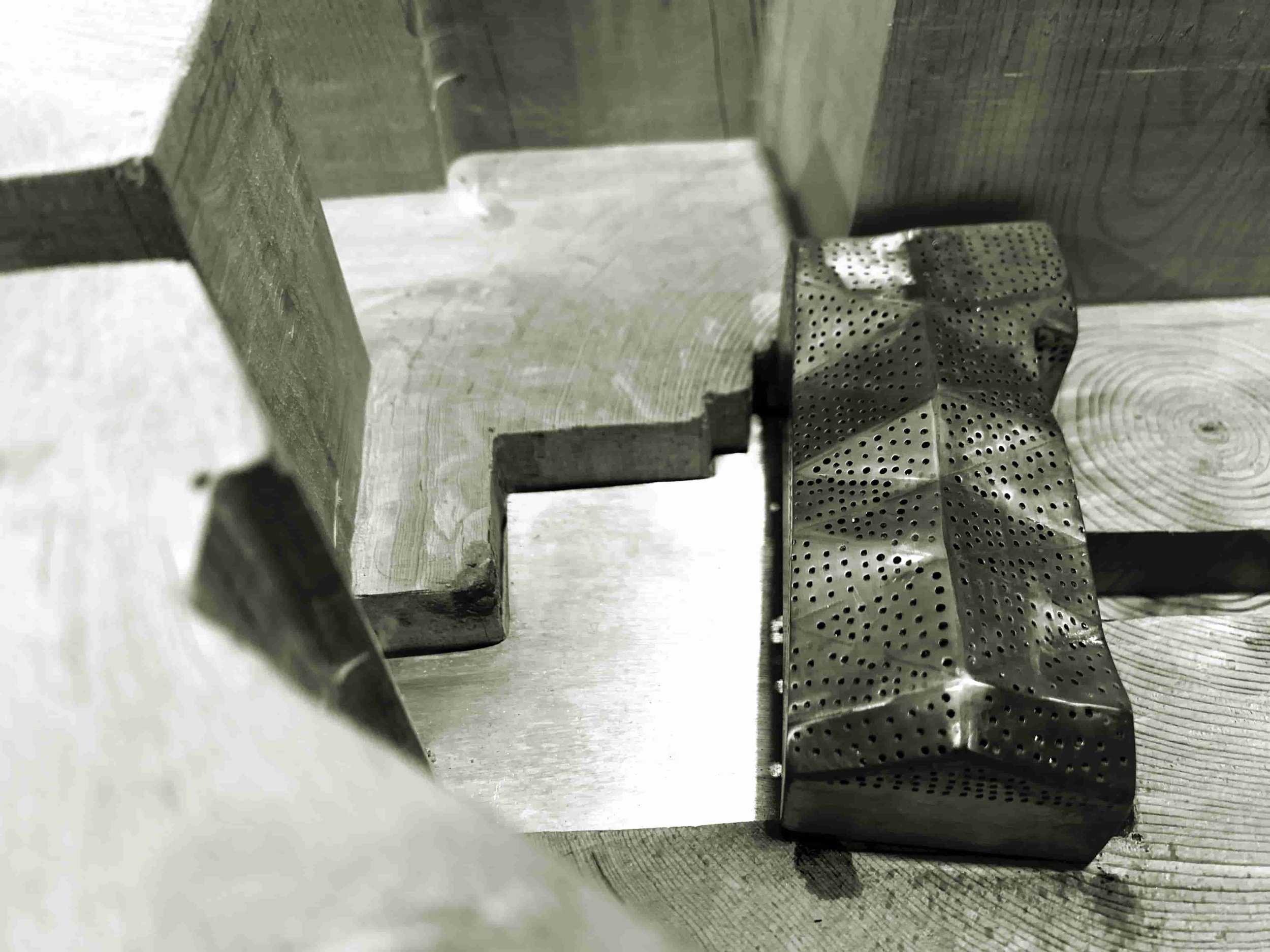

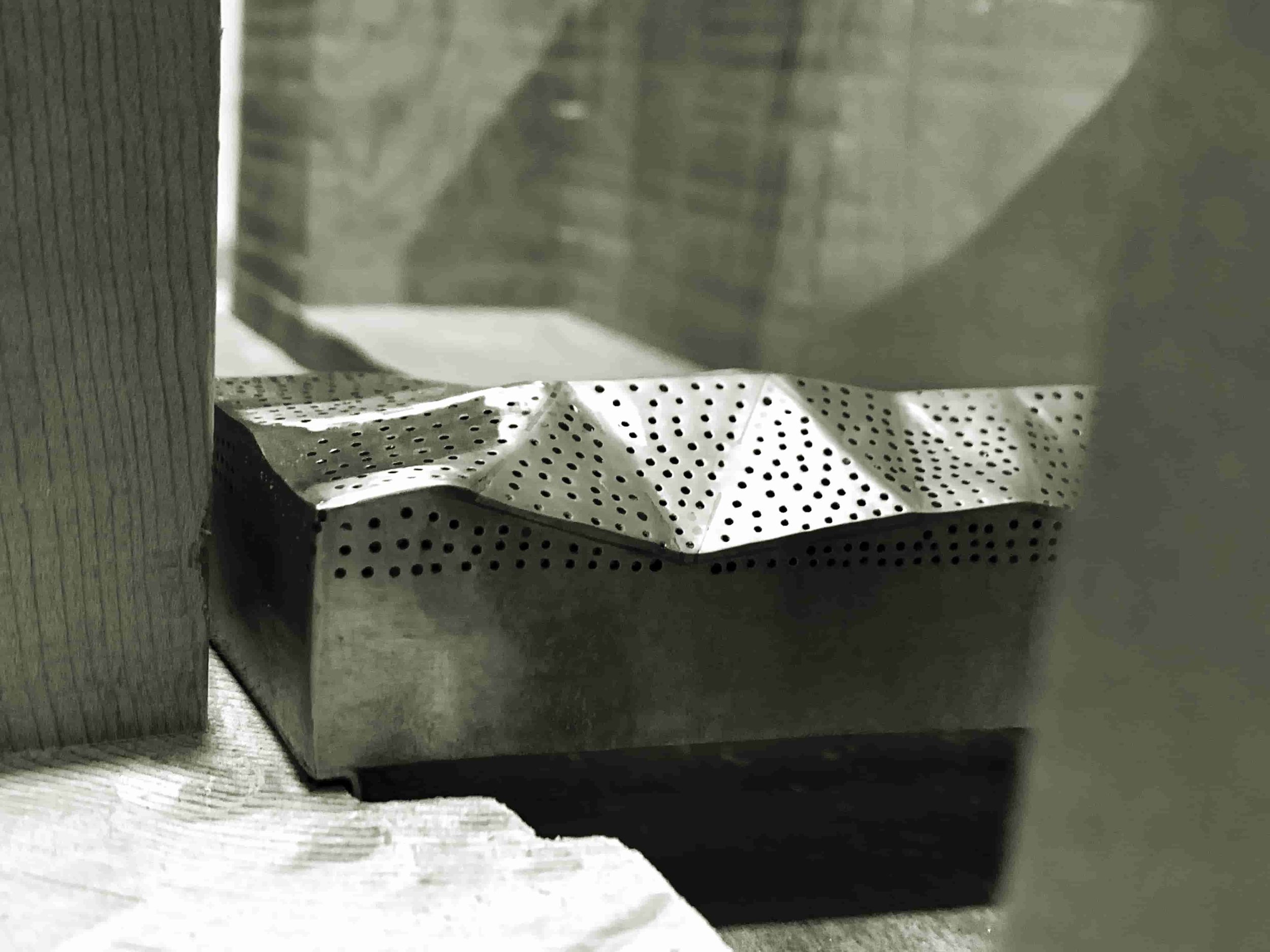

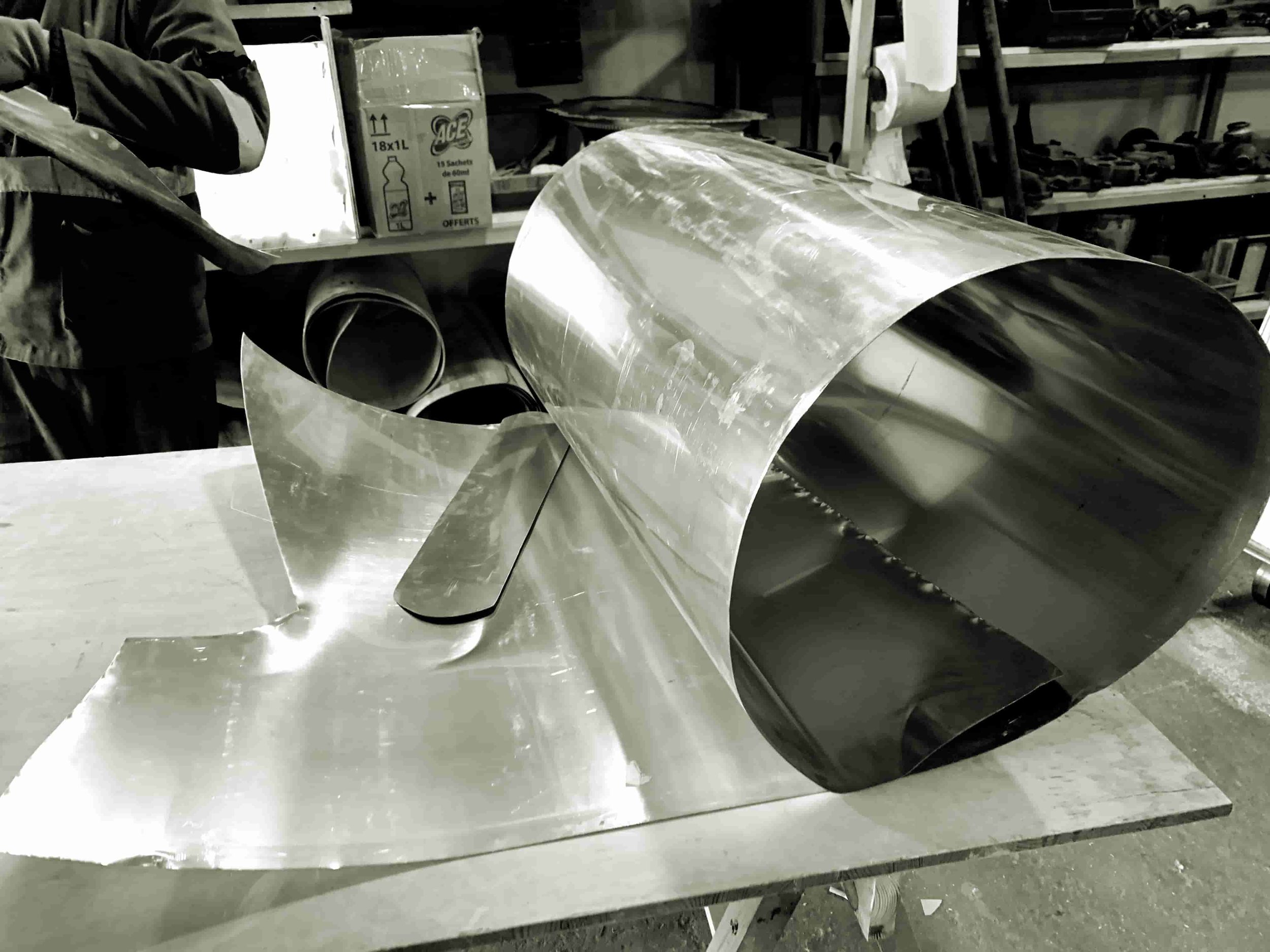

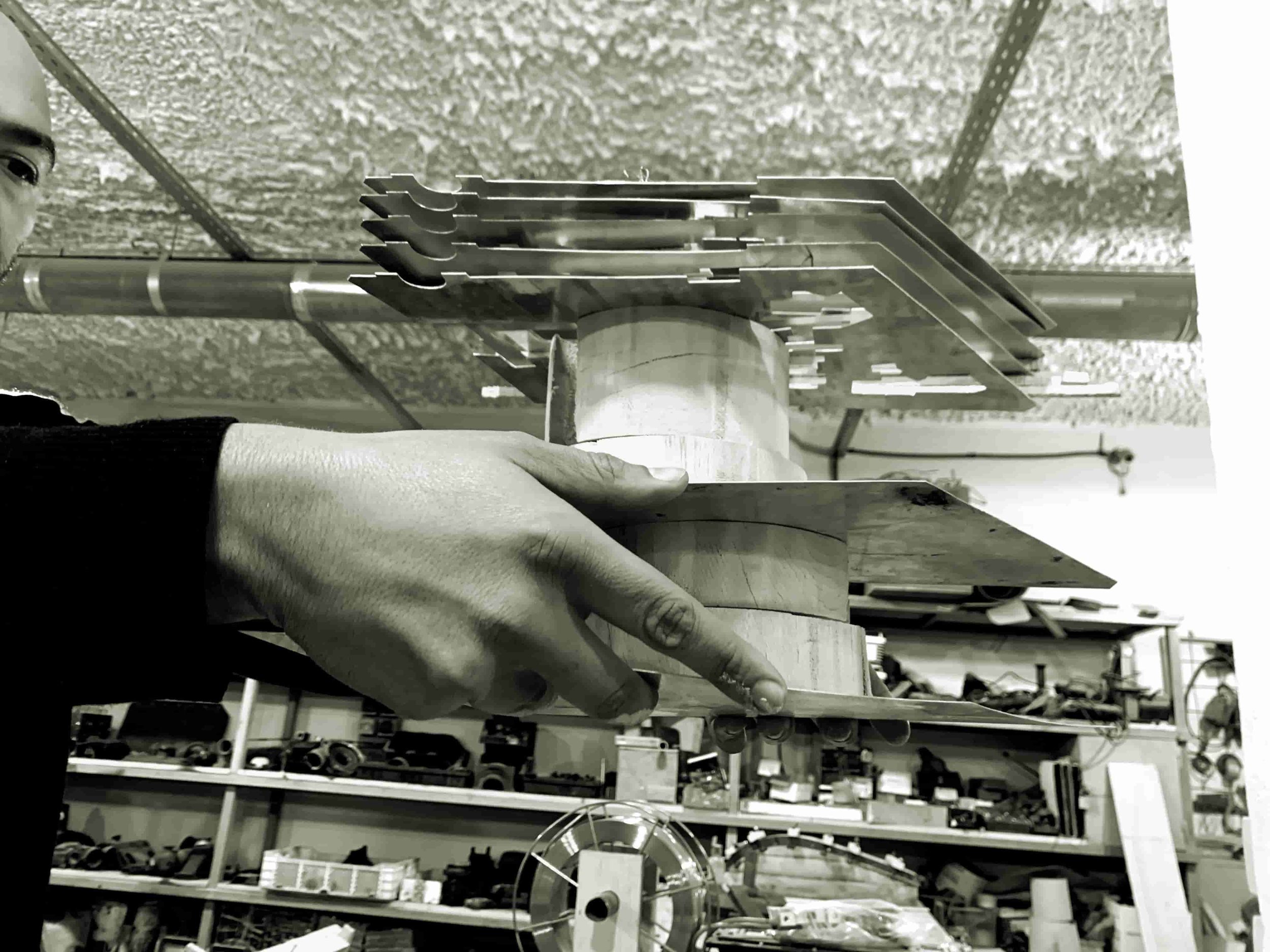

We had to decide how we were going to build the building. The first idea was to use wood, but another type, with a darker tone. The size of this piece, in comparison to the trunk, was going to make it almost unnoticed. Then we thought about 3D printing, but cedar wood deserved more nobility than simple PVC. We decided to use copper, one of the techniques mastered by the Fenduq but we did not know if they were going to be able to reproduce the irregular surface of the roof. To better show the geometry we have drawn plans with possible cutting from a single copper board, plus a 3D printed part to serve as a reference. We thought it was going to be complicated but finally the craftsmen were able to solve the creases in the roof. Once the building was in place, we saw that we had to indicate the position and area of our plot on the block, otherwise we could give the impression that the project was limited to the current construction, while in reality our project was the garden that would occupy the entire plot. In this regard, the craftsmen added another copper piece over the entire surface of the plot.

We had one last question to decide. Should we give a finish to the wooden trunk or should we leave it as it was? The appearance of the wood was important and even if we could go on the idea of protecting the wood with a varnish, we should not fall on finishes closer to the furniture, the design object or the architectural model. Again, it was important to stay consistent with the nature of the material. It was “Dragon” who told us: “when the wood is so good, it should not be treated, I have a cedar wood table at home and I have never varnished it, when it is is dirty, I sanded it and that's it, in addition, it leaves the room with a magnificent smell, in my opinion, it is necessary to clean with compressed air the shavings and wood dust and that's it”.

The model in the exhibition once finished.

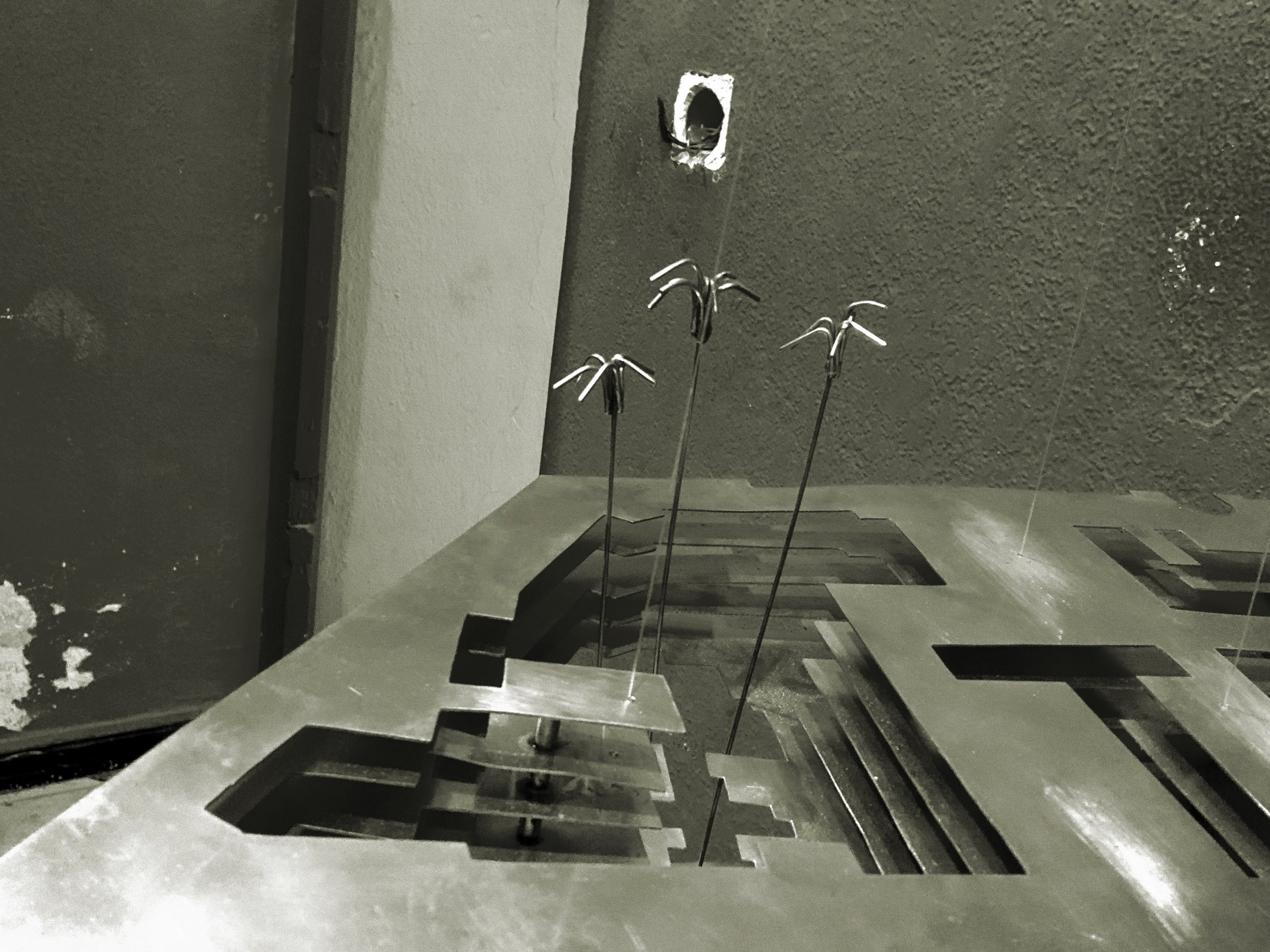

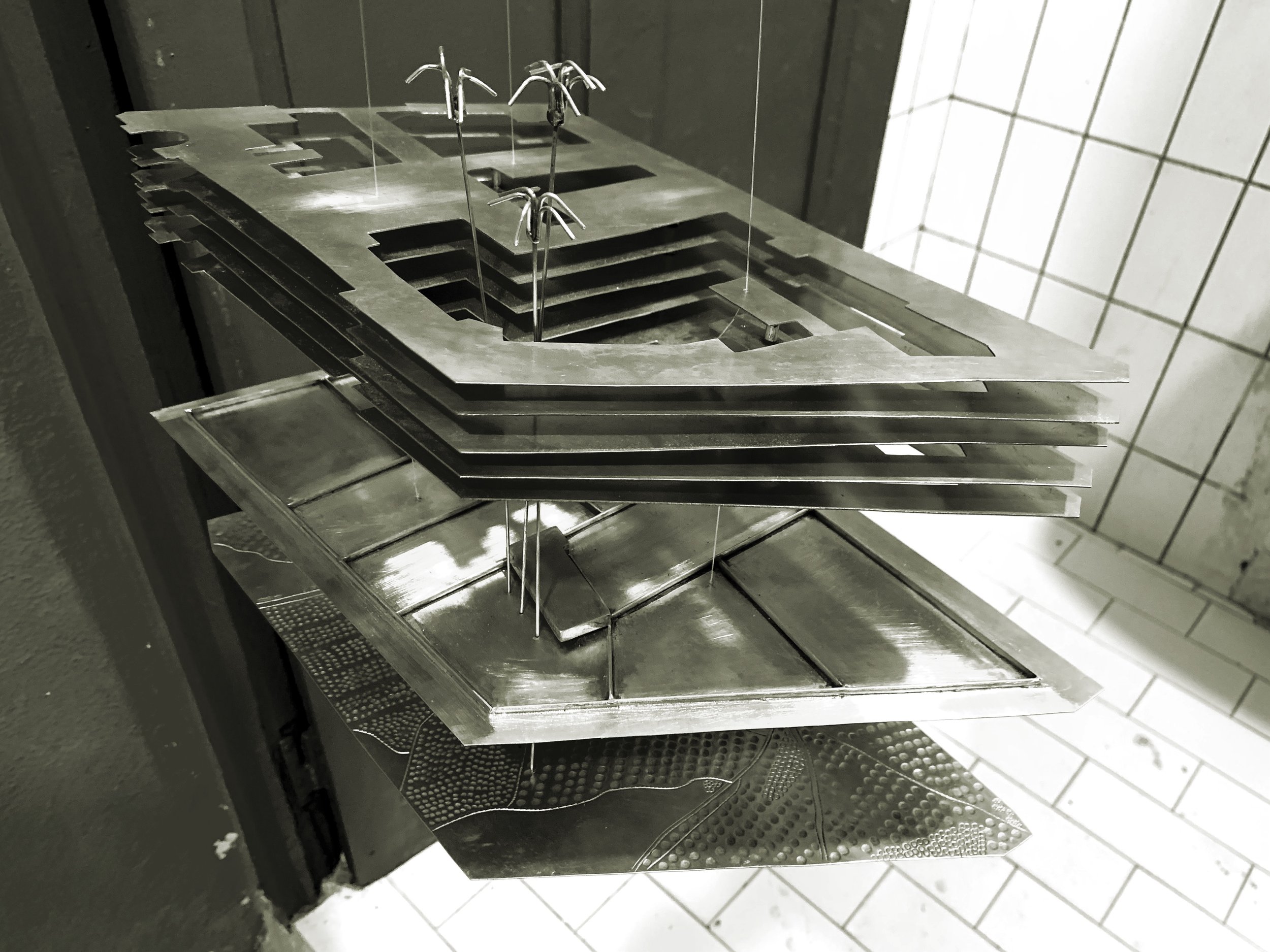

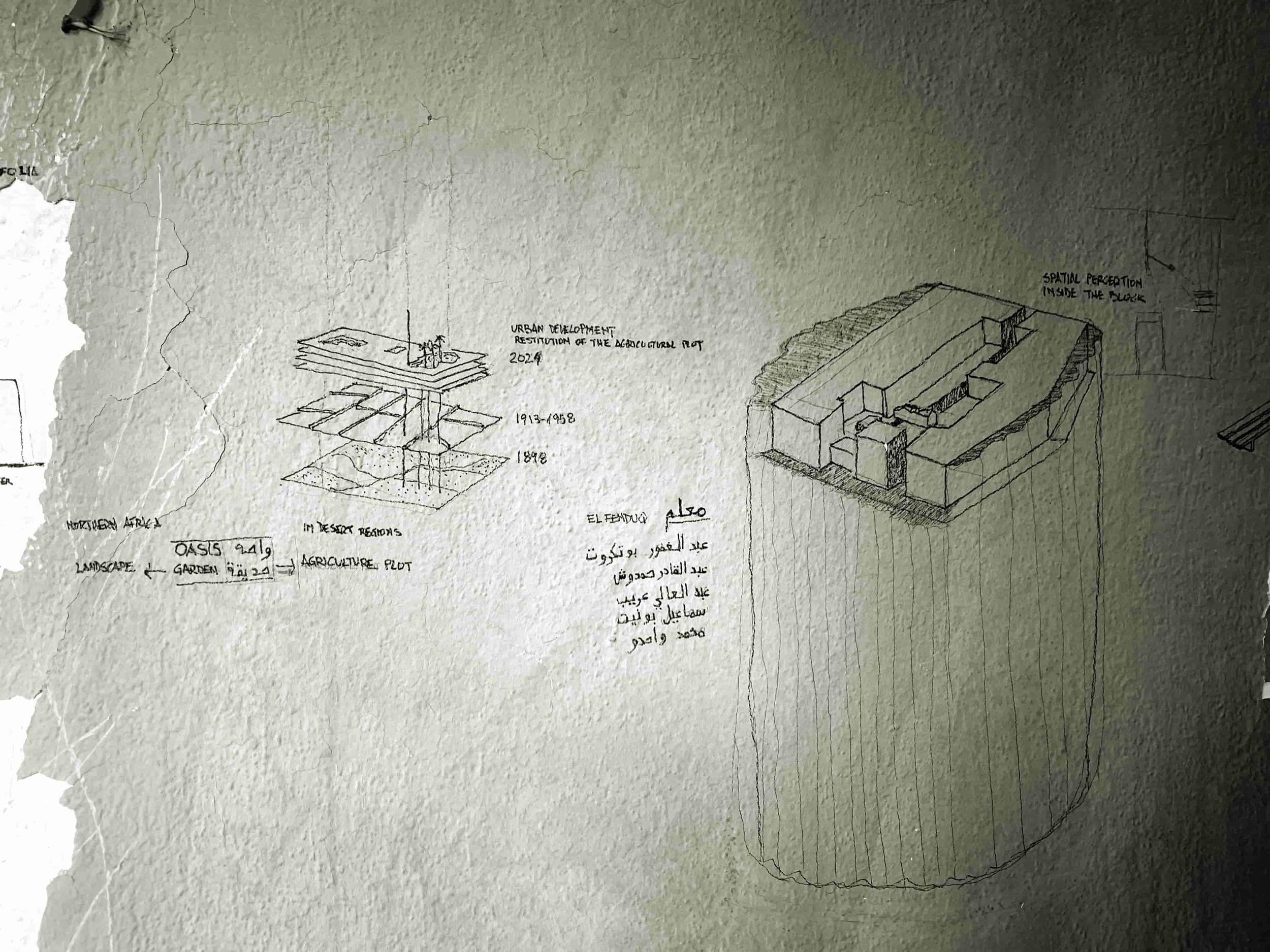

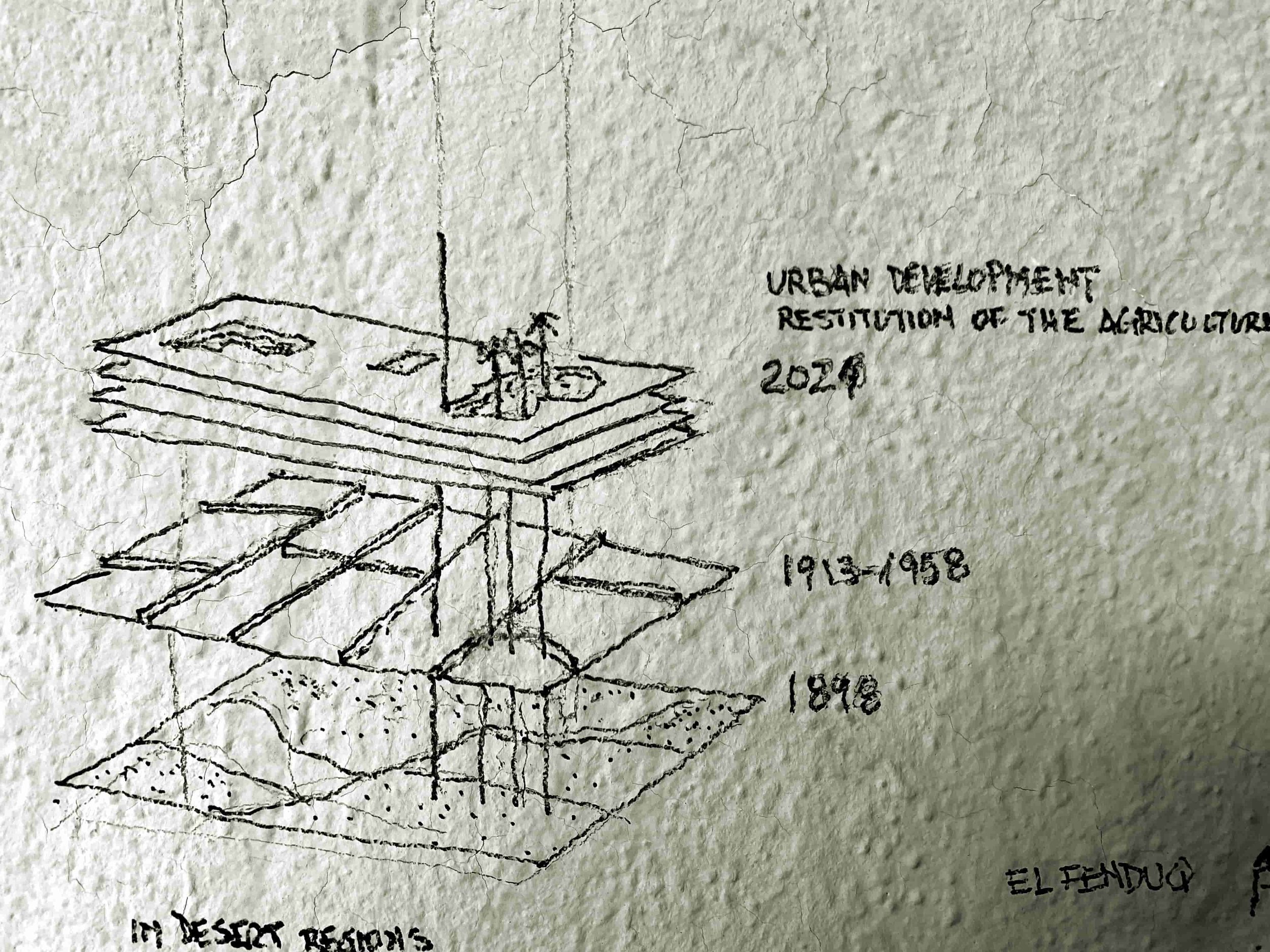

04.2 City block evolution model

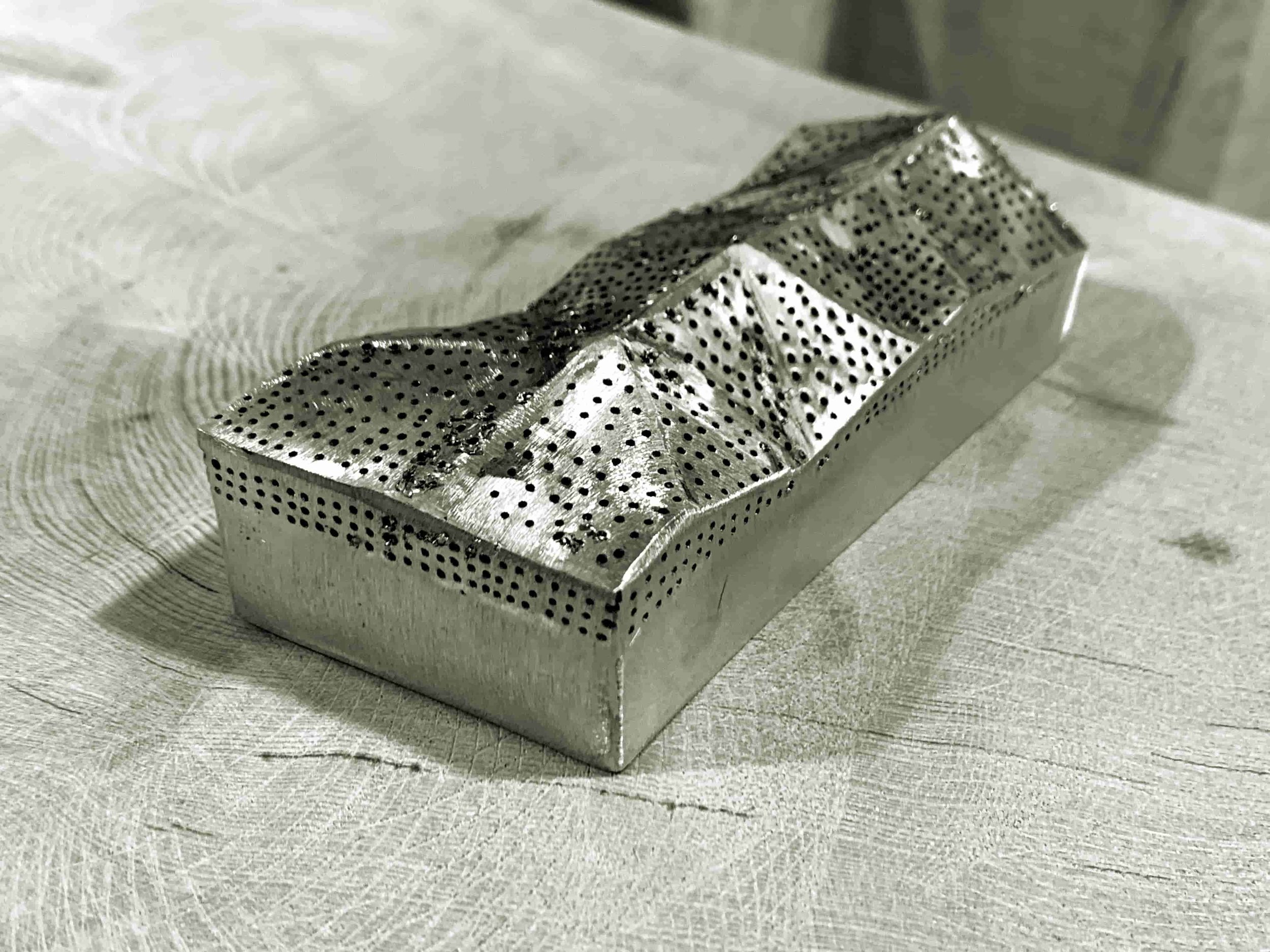

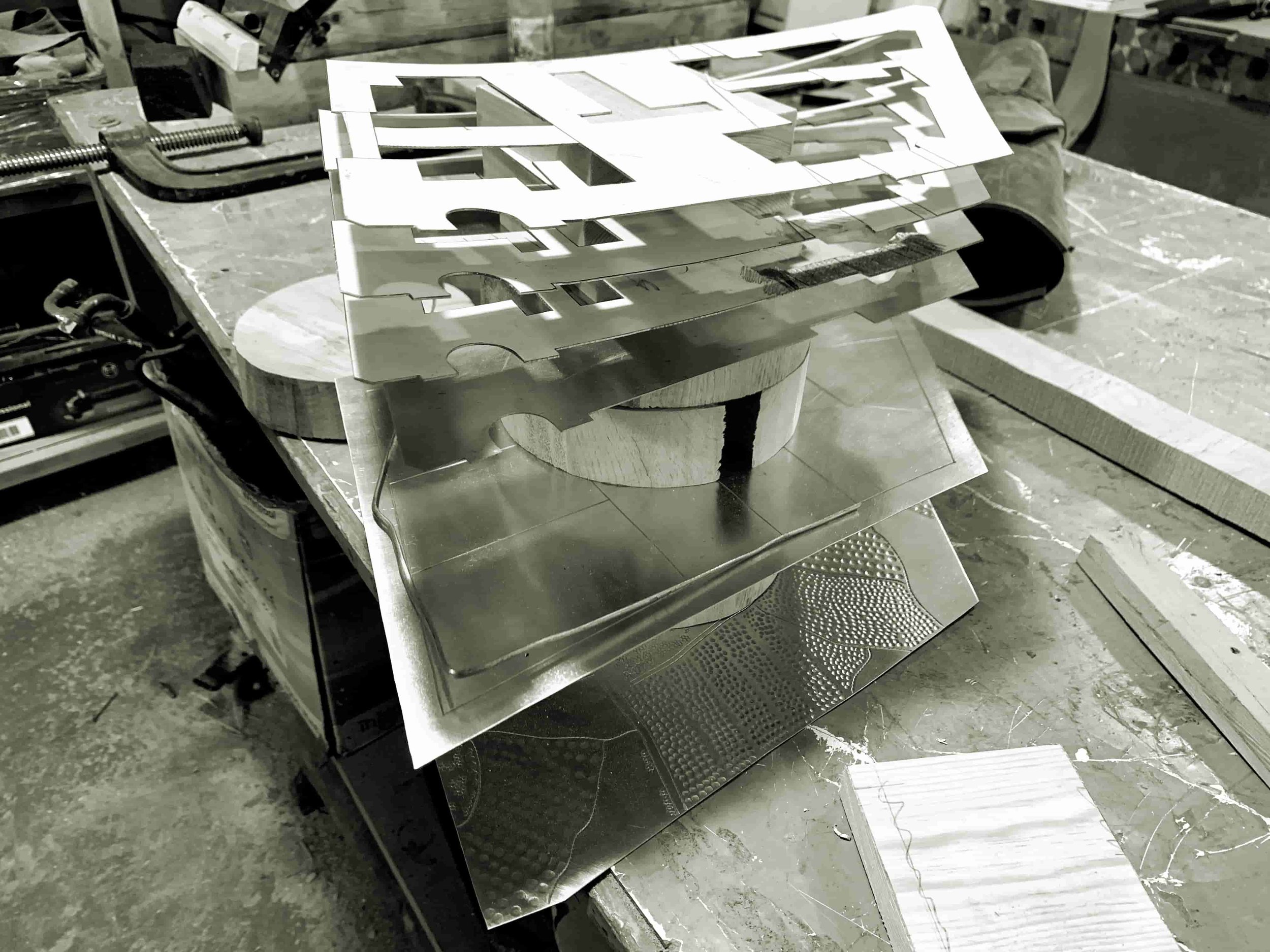

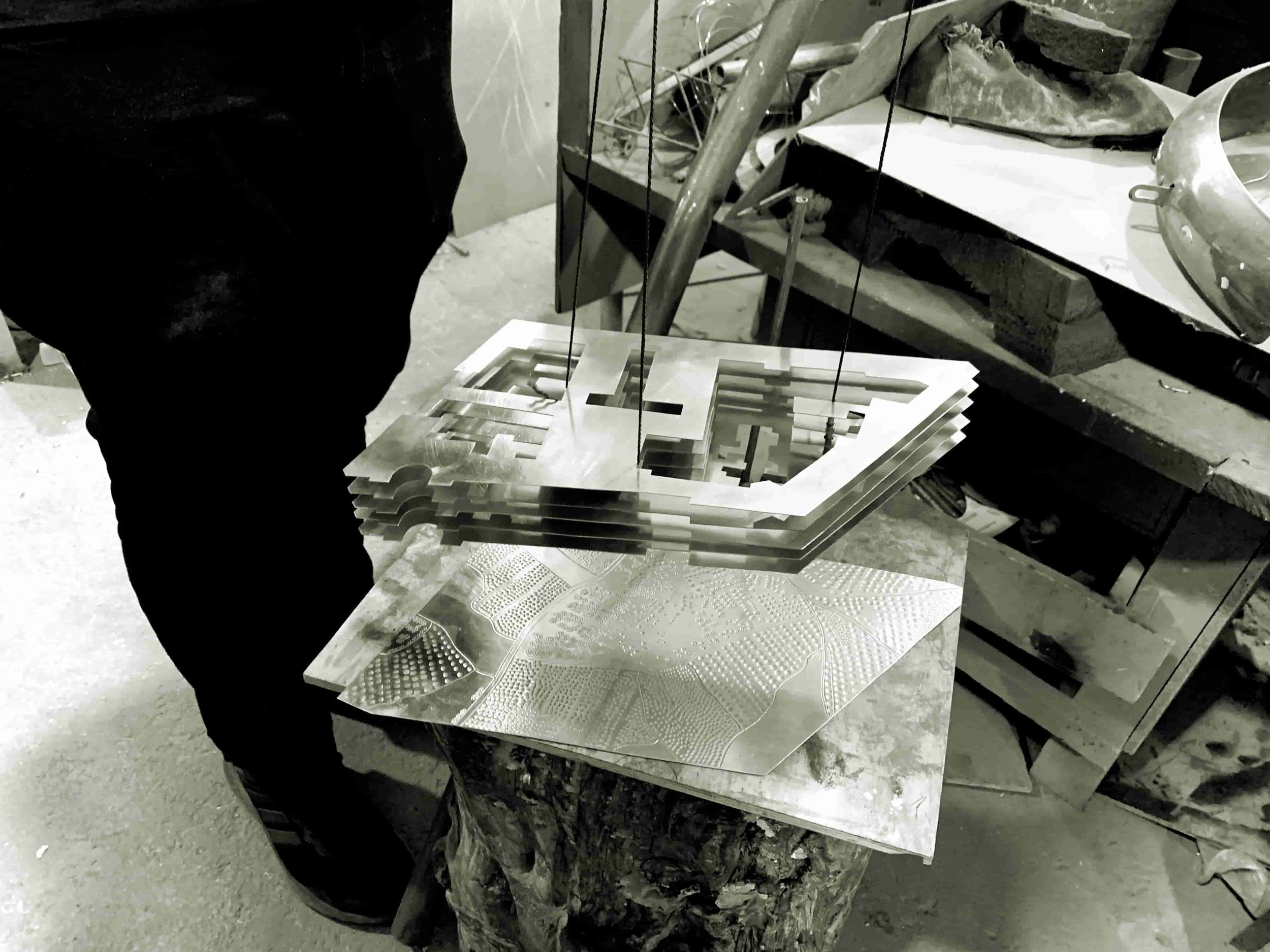

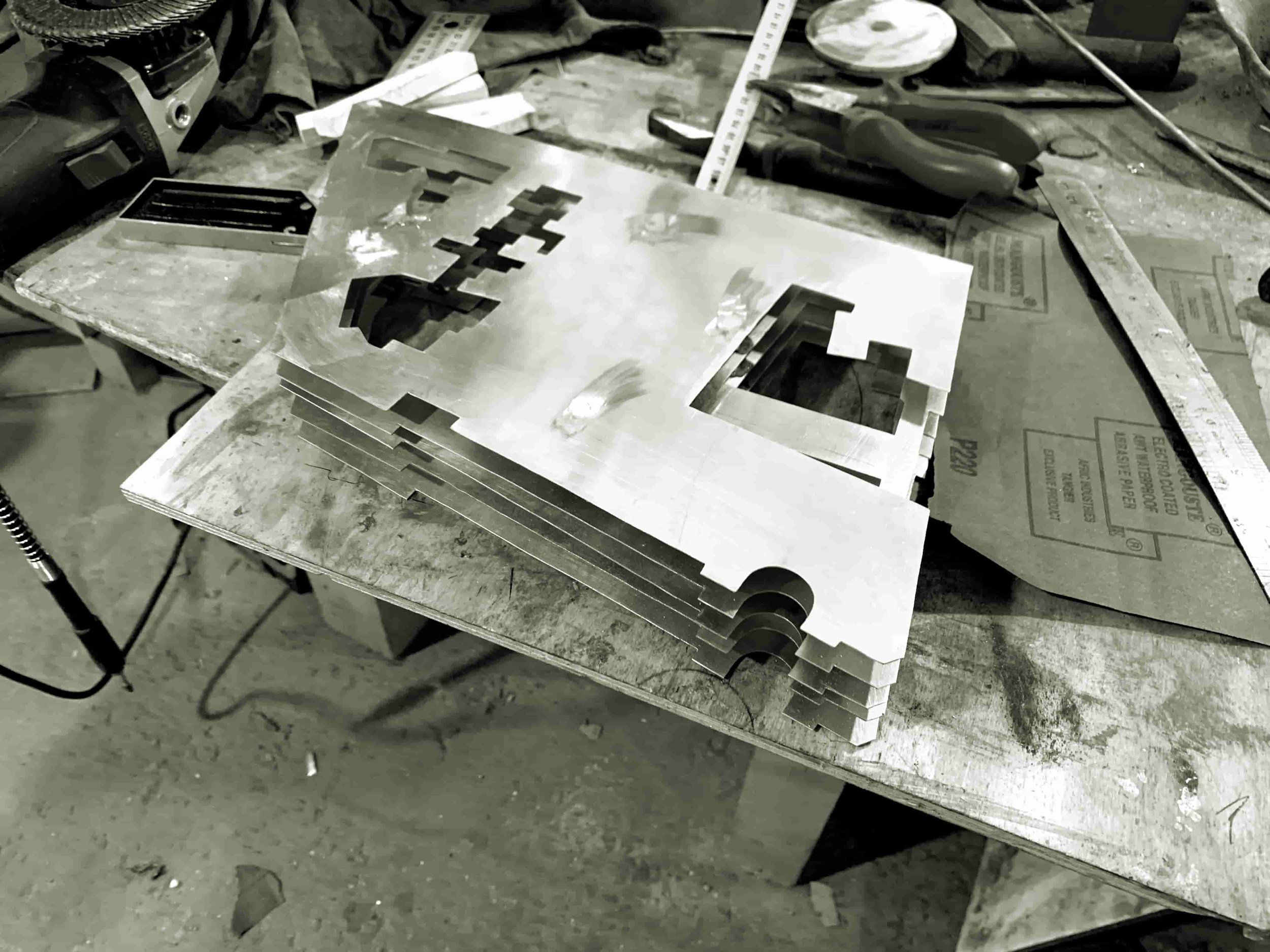

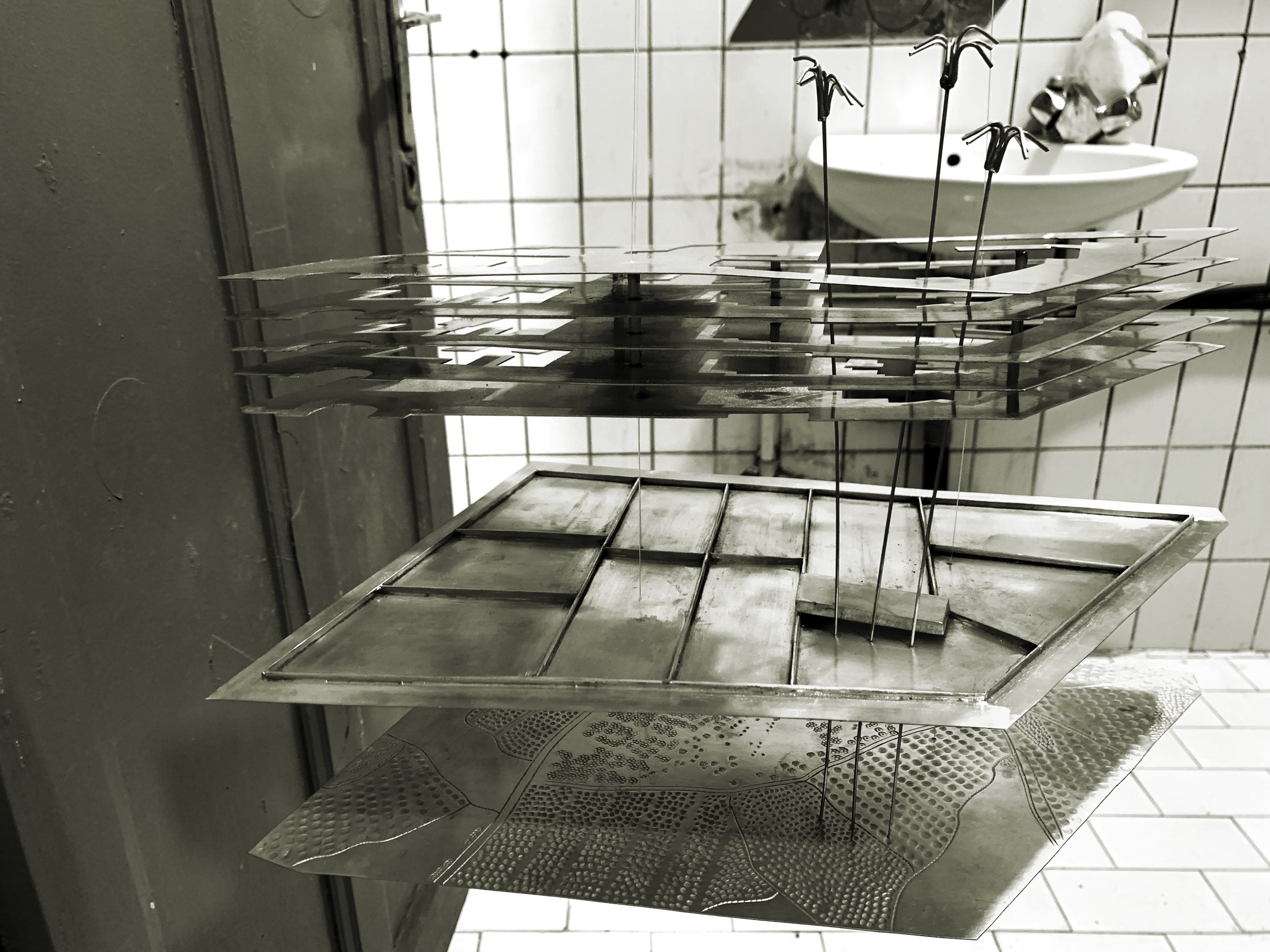

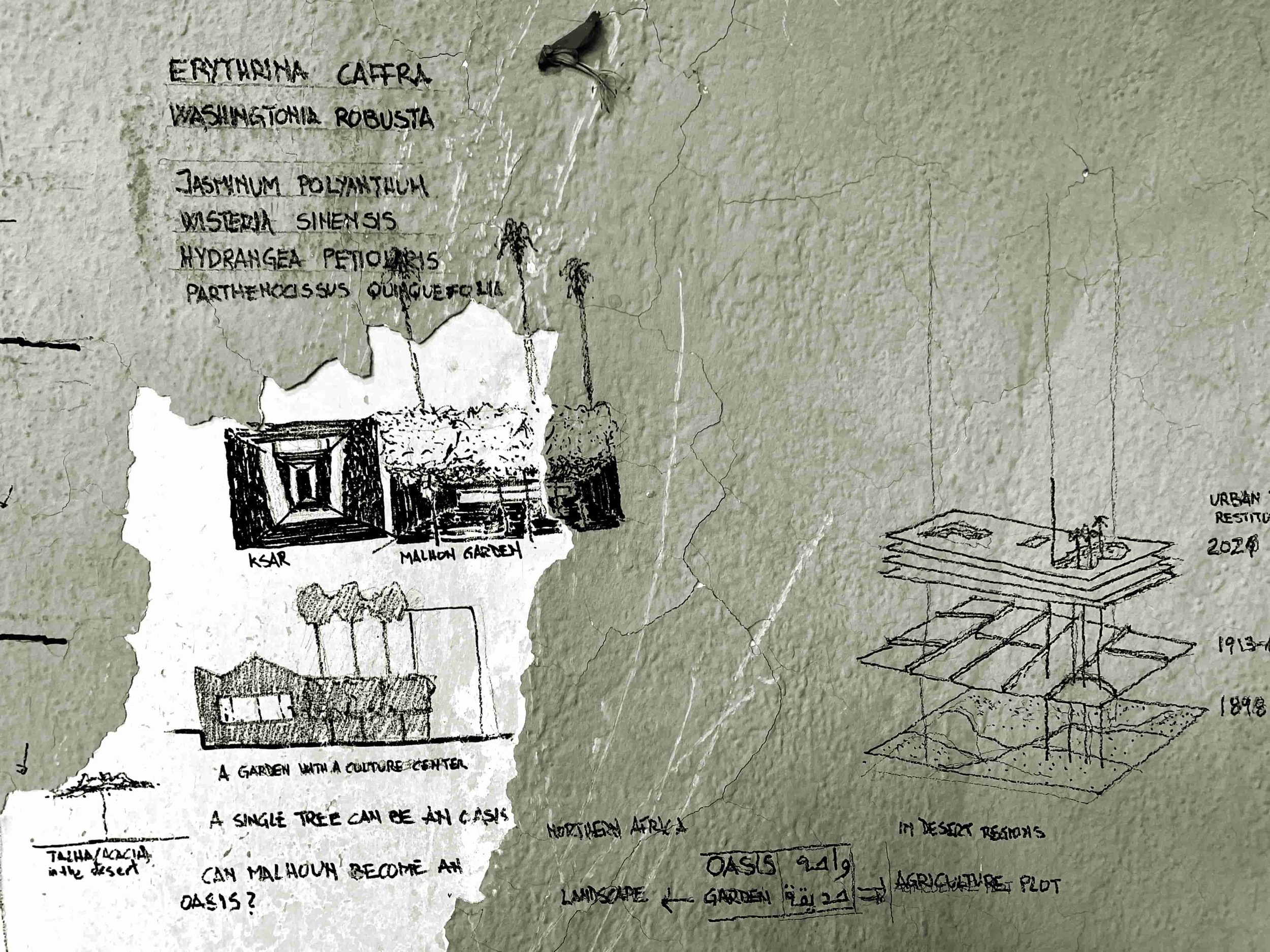

The other idea that seemed important to us to notice was the recovery of the plot as a green space and to explain the evolution of our urban block from the foundation of Marrakesh in 1070 to the present day. On the one hand, we intended to rely on the existing planimetry from 1898 but we did not know how to represent it or with what material. We thought of wood, plexiglass, copper and nickel silver, also to make a board for each of the evolution of the oasis and urban development of our urban block. But how could we show these boards and this evolution? We thought about hanging them on the walls but that seemed too classic. Once again, we went back on our (architectural) ideas to keep the essence and show them not as architects but as a craft object, as we had done with the first model. Thus, it was clear that the solution was to superimpose the different plates, according to the evolution over time, by suspending them.

© Driss Benabdallah

© Driss Benabdallah

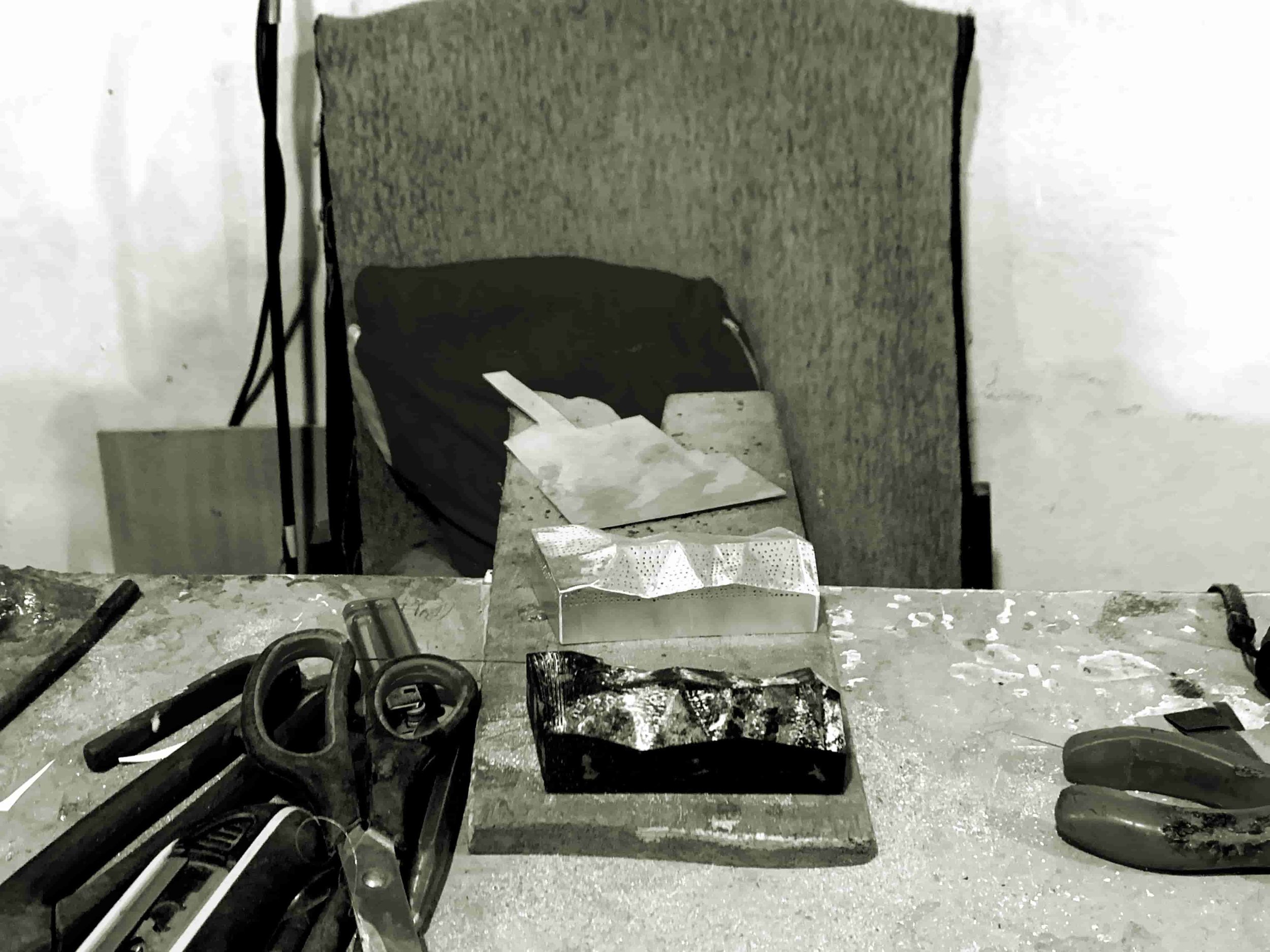

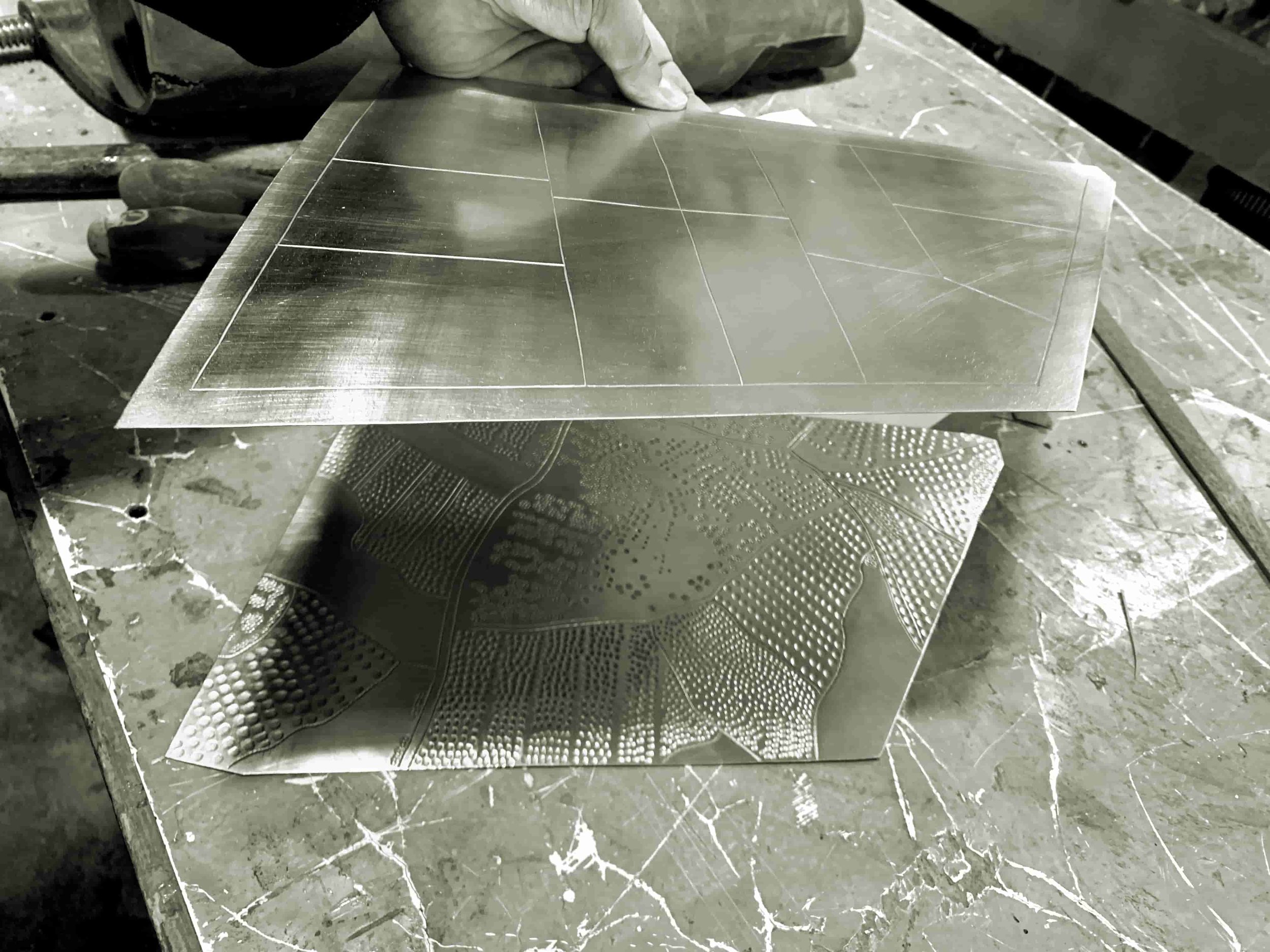

In order to decide which phases of urban development we were going to show and what to do with copper, we “examined” the Fenduq workshop. By looking at the stored materials, work in progress, samples and scraps and above all by talking about the possibilities with the artisans Abdelaali Arib, Ismail Bounit and Hassan el-Mouaddine, and with Eric, we started to think.

However, we were confronted with very sensitive questions that are present nowadays in Morocco, whether in architecture, in contemporary art or in crafts; the representation of Moroccan culture through stereotyped images. If one builds a public building, one must see on the facade materials (tiles, zelliges, plaster), forms (arcades, roof with two or four slopes), patterns (copied from zelliges, plaster, doors and wooden ceilings) so that the building can be recognised as Moroccan, as if the country had stopped at a moment in its history, as if nothing had changed either before or after that precise moment, and considering the whole territory as a single entity with the same customs, cultures and histories.

Architecture has been constantly changing, adapting to lifestyles, economy, construction techniques and materials. For example, we see the medinas as uniform neighborhoods, as if they had been built all at once, without considering the constructive process, their occupation and their densification. Same for the houses of these medinas, the changes of the constructive and structural systems (brick arcades, wooden beams, steel beams, now concrete beams) throughout history, meant the modification of the dimensions of the courtyards, rooms and even the interior distribution (moreover directly related to the evolution of the family composition). For this reason, it is fundamental to understand the reasons and mentalities that gave rise to a city, a house, a craft object, a work of art, rather than remaining in the image of a product. Sometimes the heritage that should be protected would be these mentalities rather than the object produced.

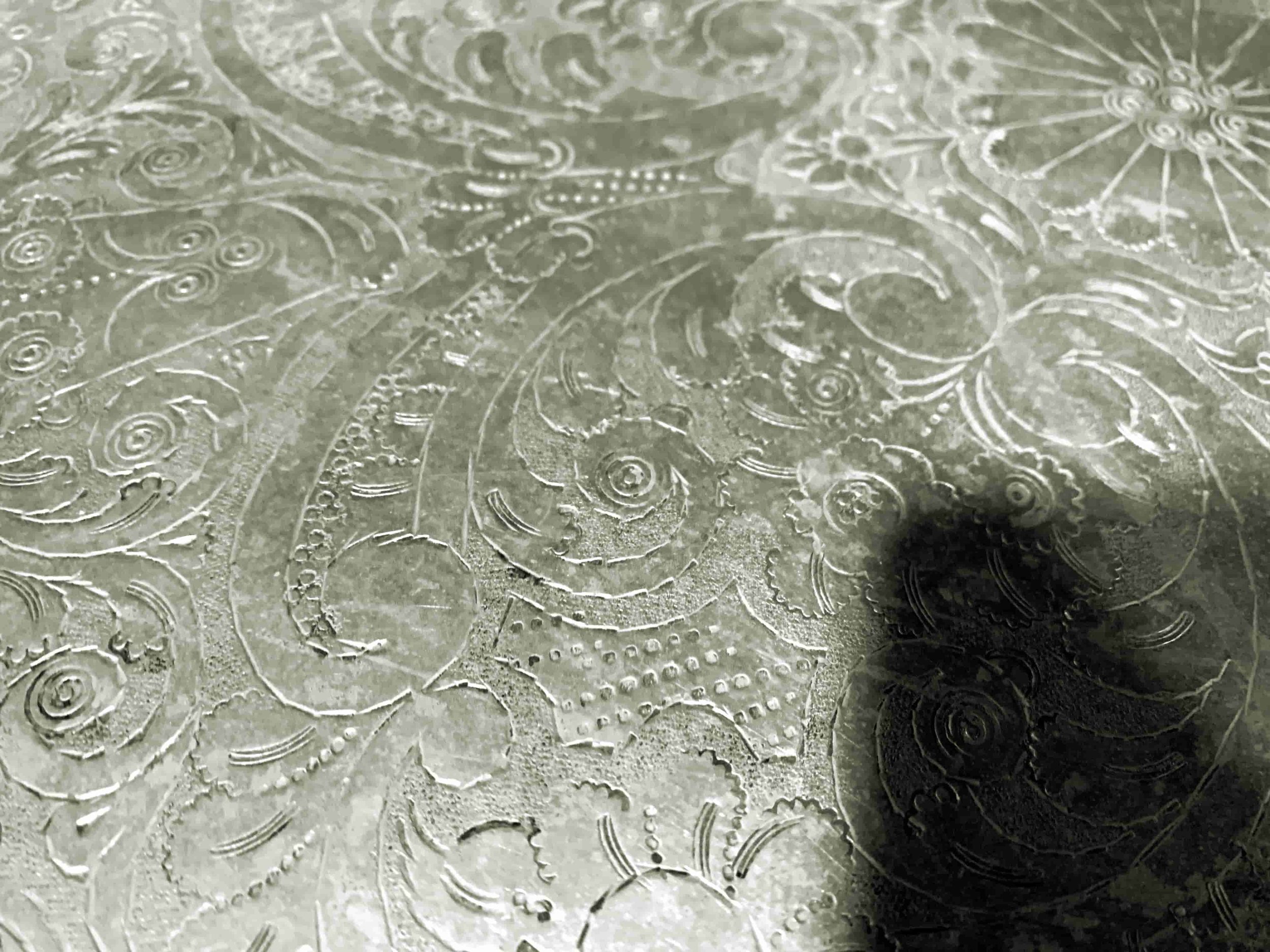

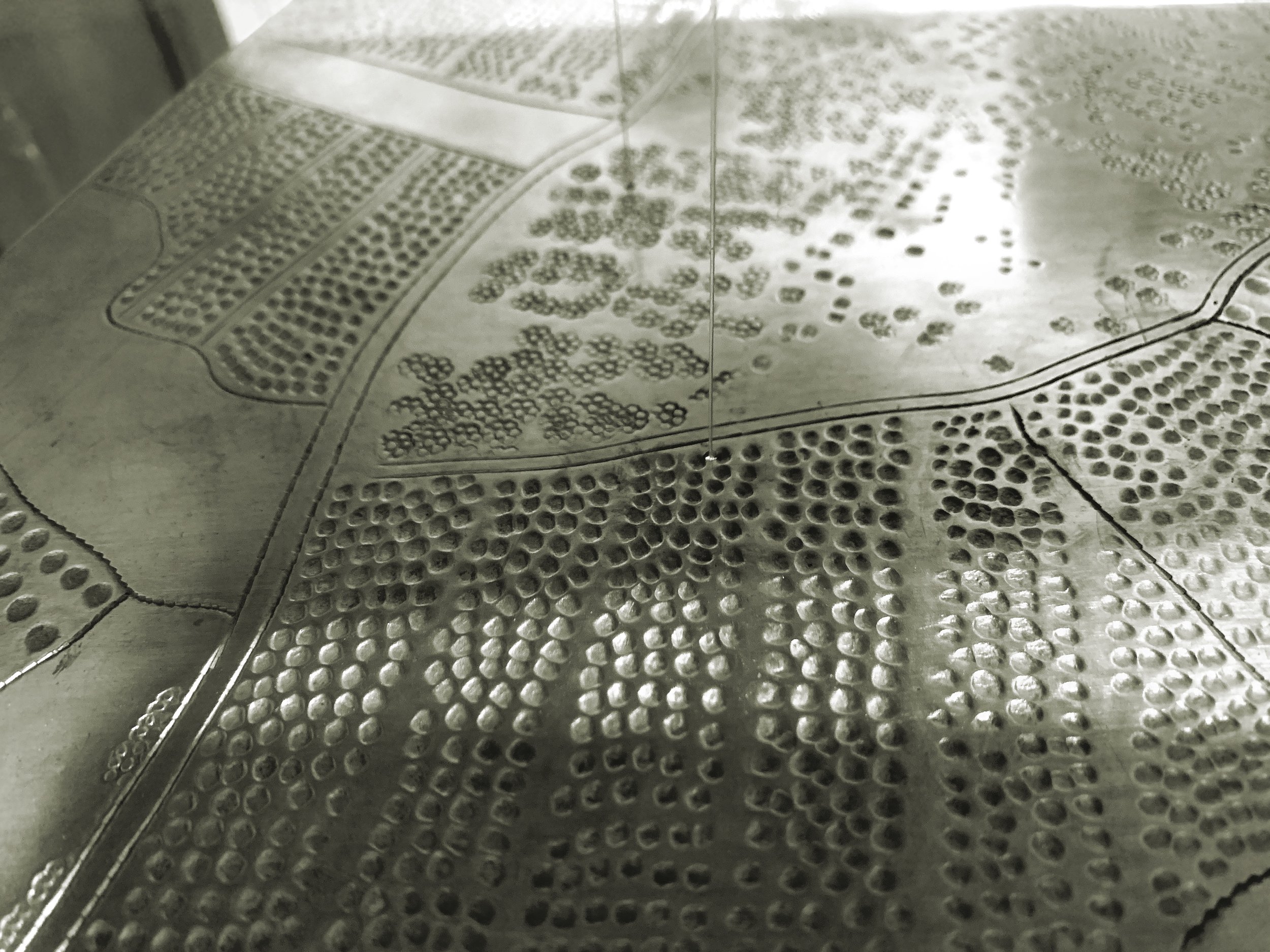

Returning to our model, at the time of finding a method to reproduce the frame of agricultural spaces, we were shown the patterns that are used for various copper and nickel silver objects (lamps, trays, teapots, etc.) which Eric also uses in most of his works. However, for me, it was too redundant because we were in the process of reproducing a Moroccan oasis, with materials belonging to Moroccan craftsmanship, with Moroccan craftsmen and with Moroccan instruments and techniques and all that was not enough to consider a object as Moroccan craftsmanship? It was necessary to add typical patterns to make it obvious that it was Moroccan?

We decided above all not to use “classic” patterns in the model.

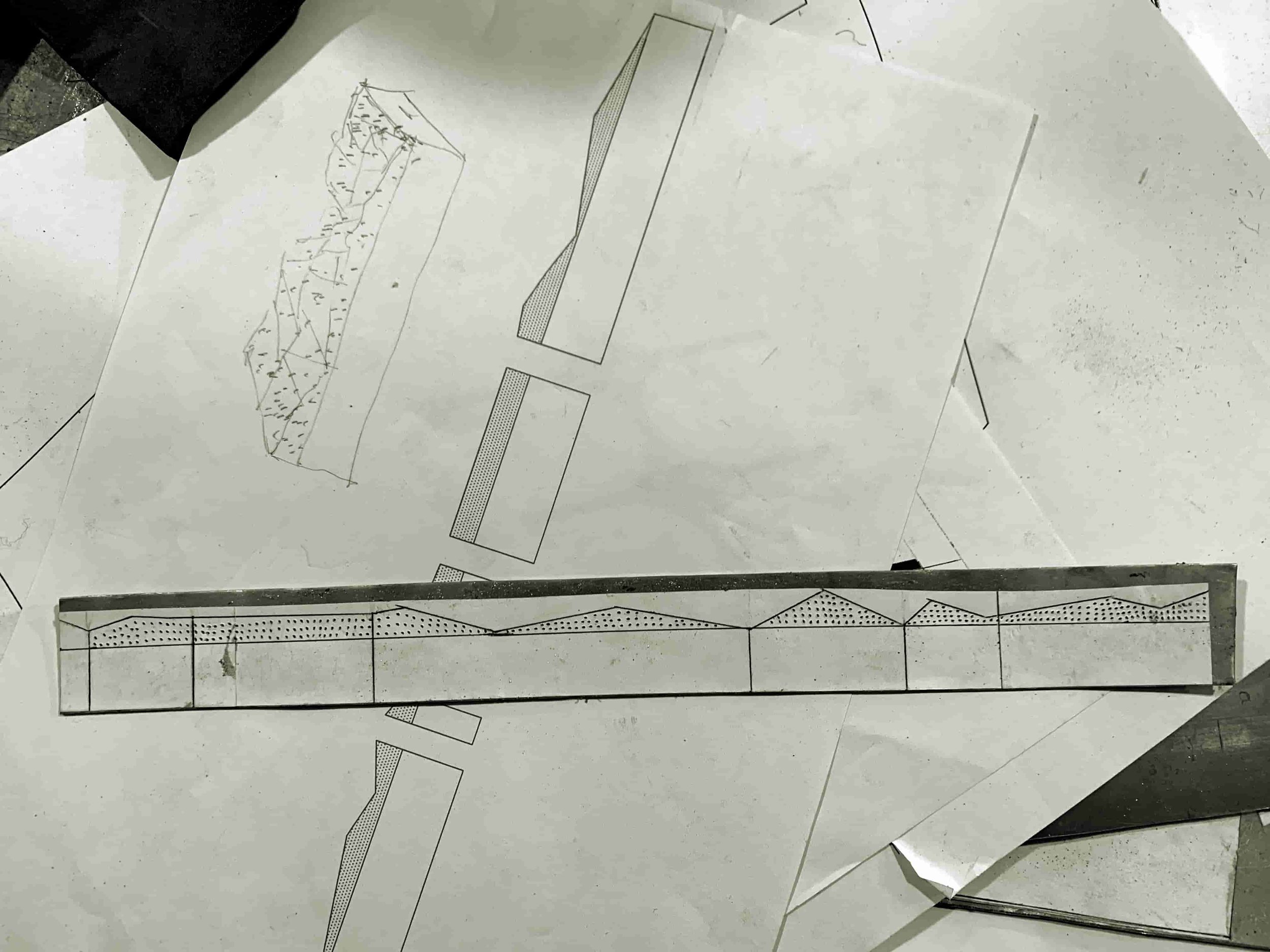

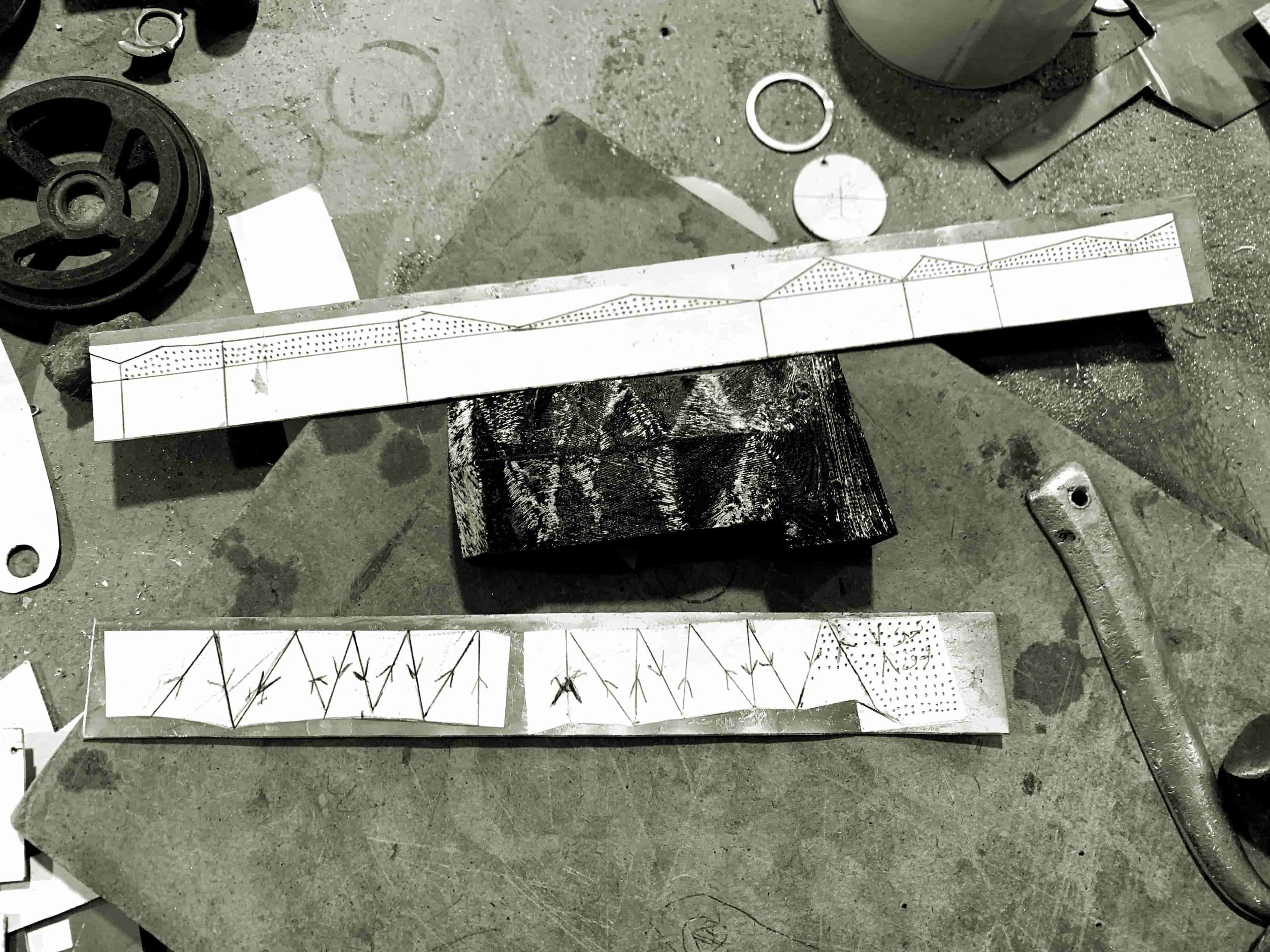

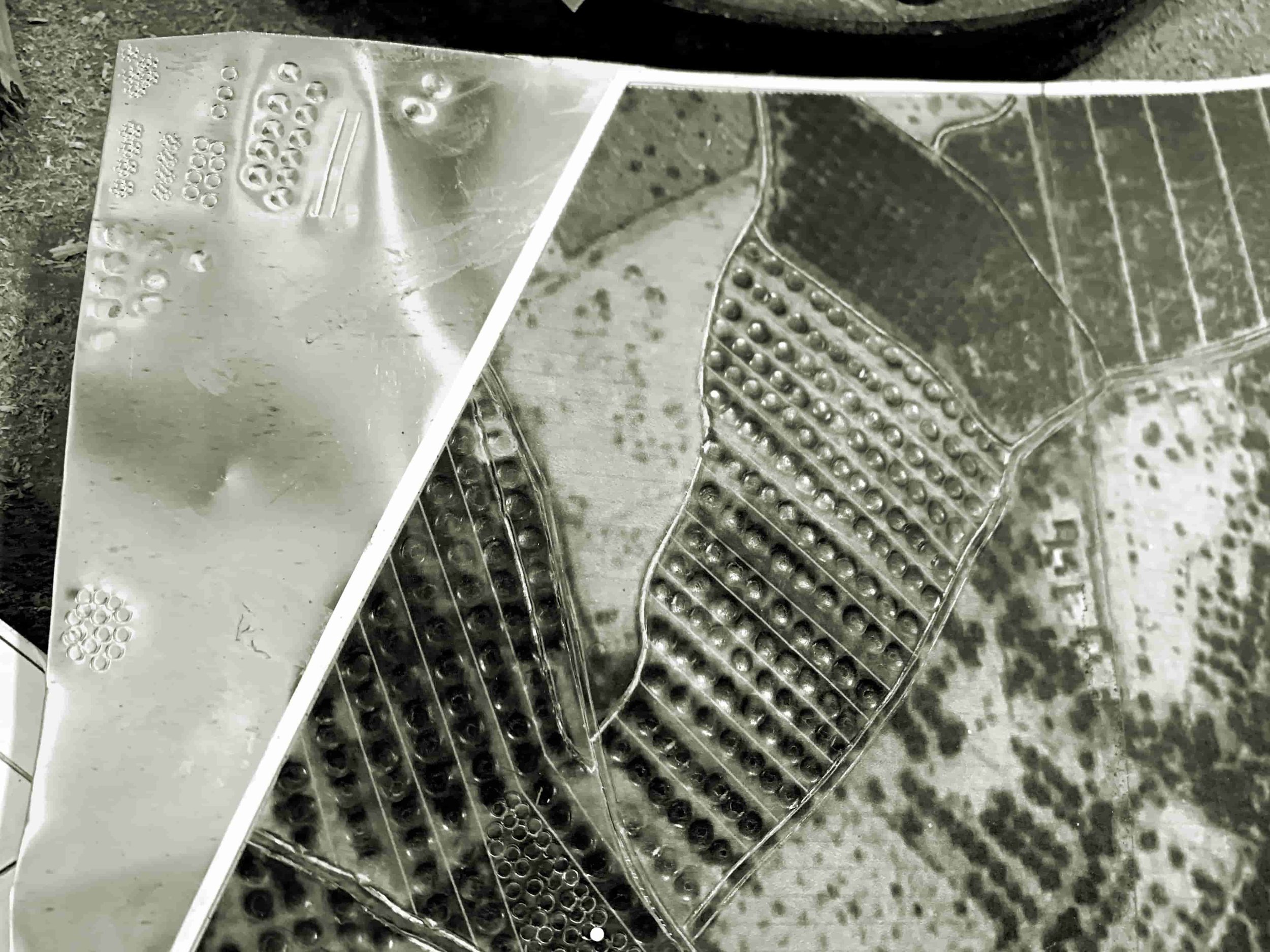

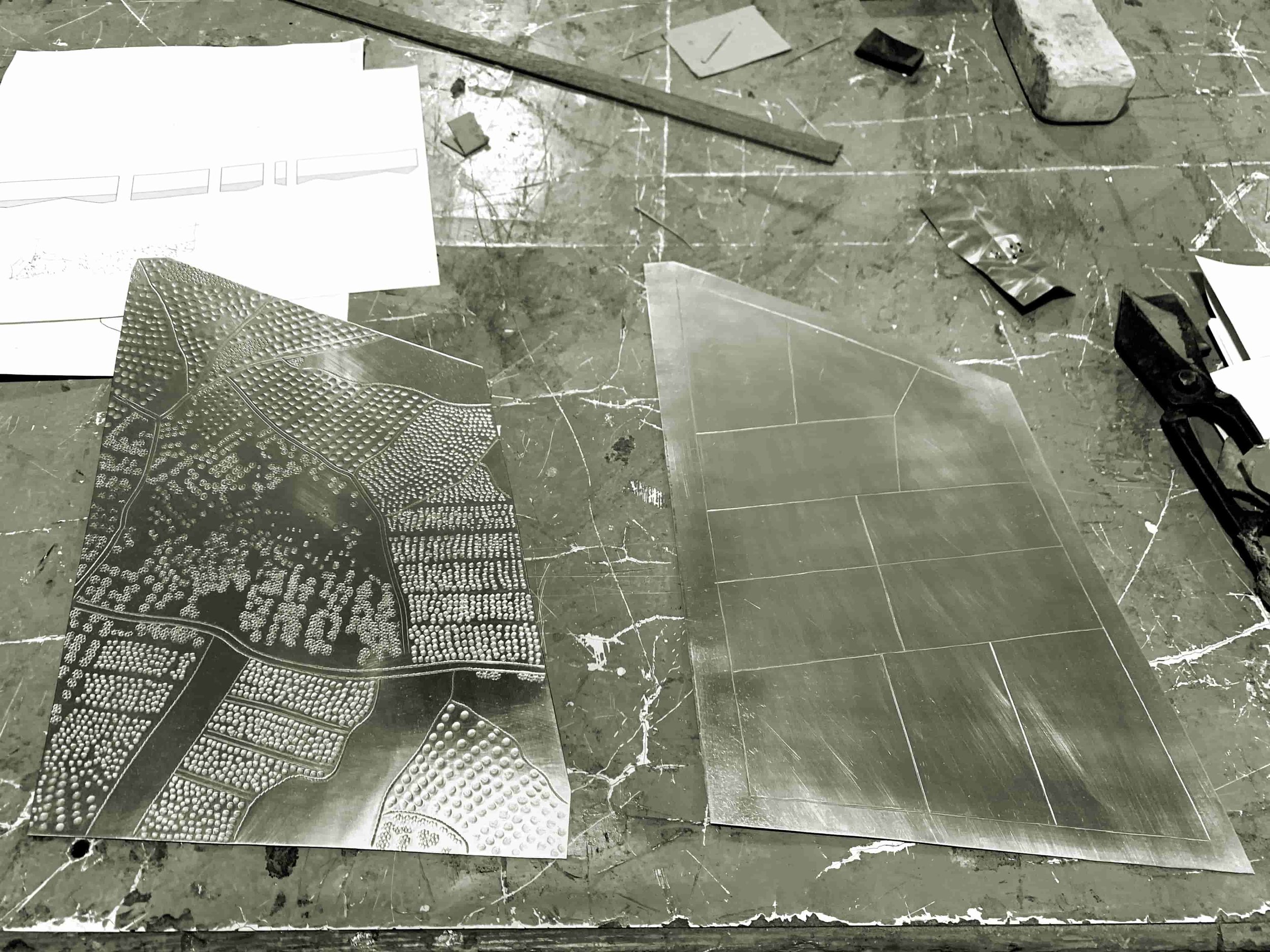

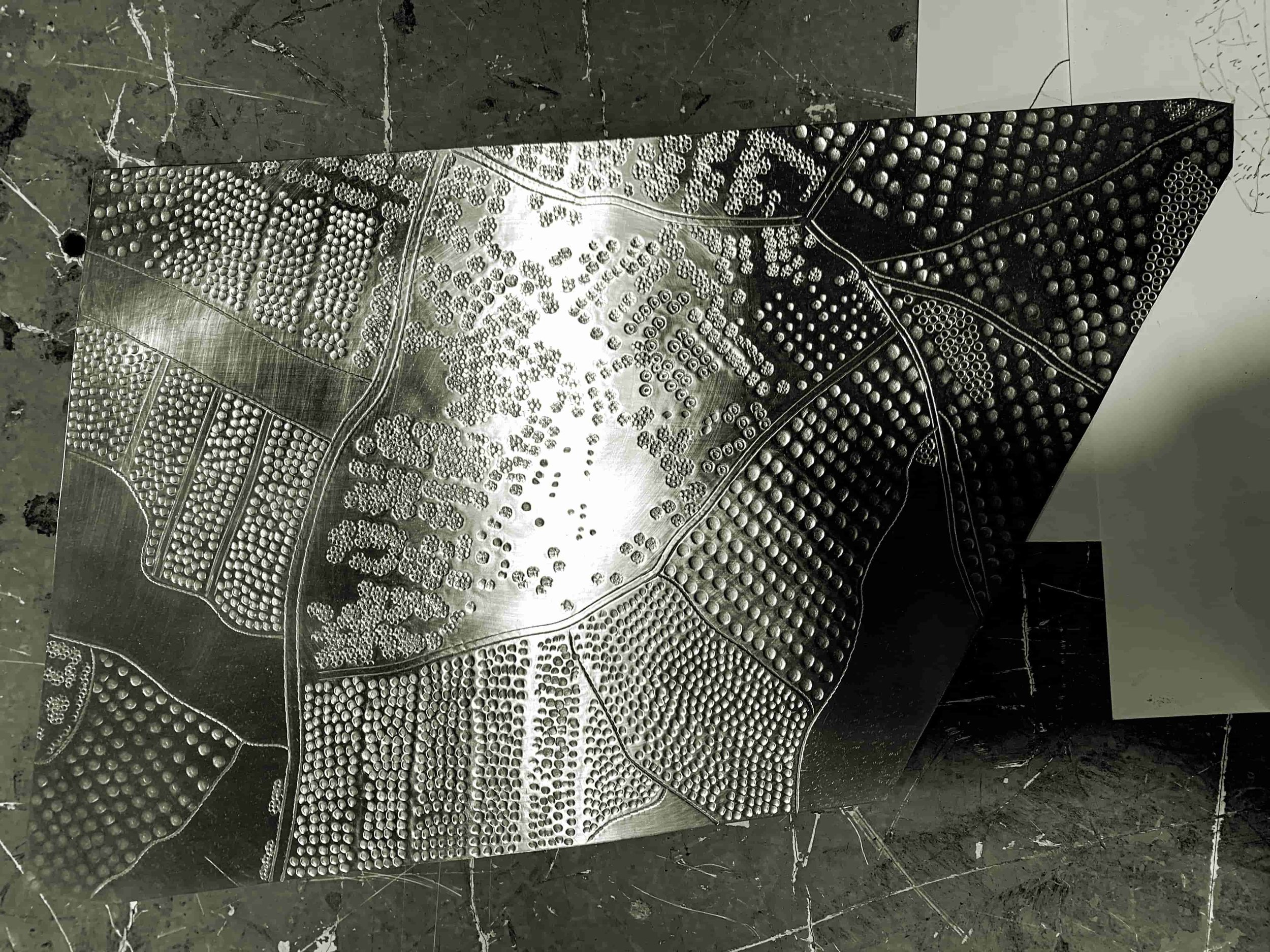

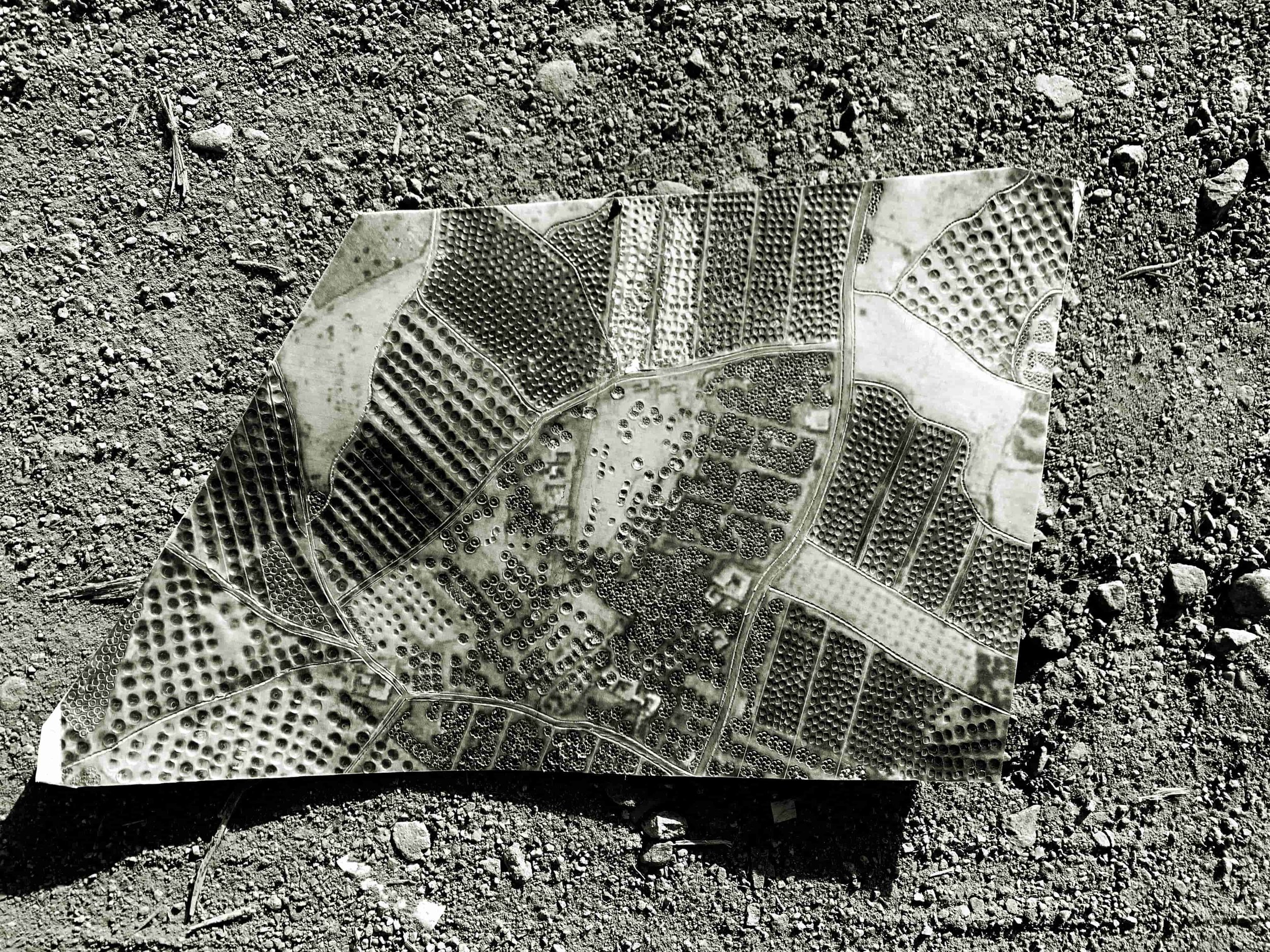

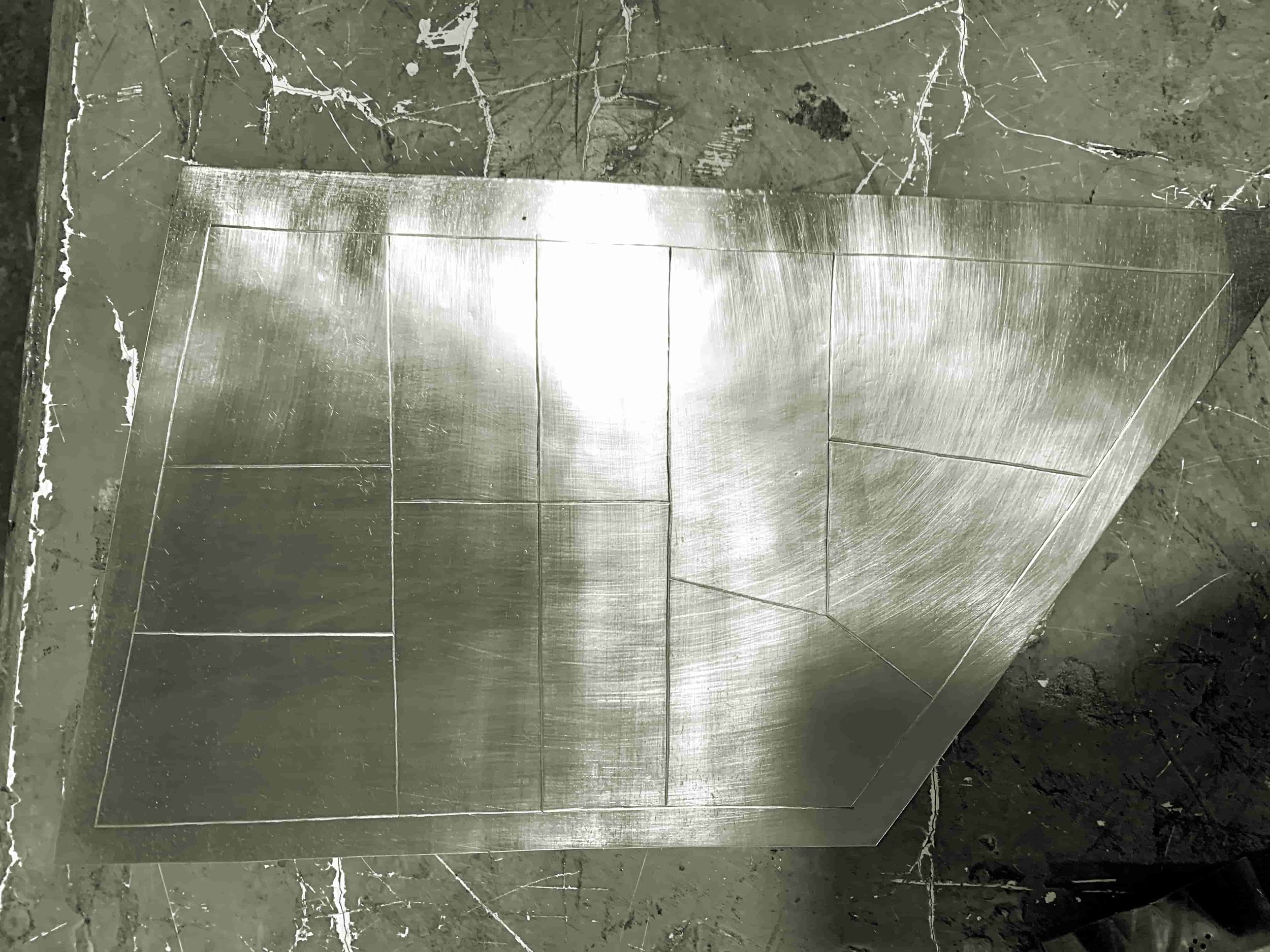

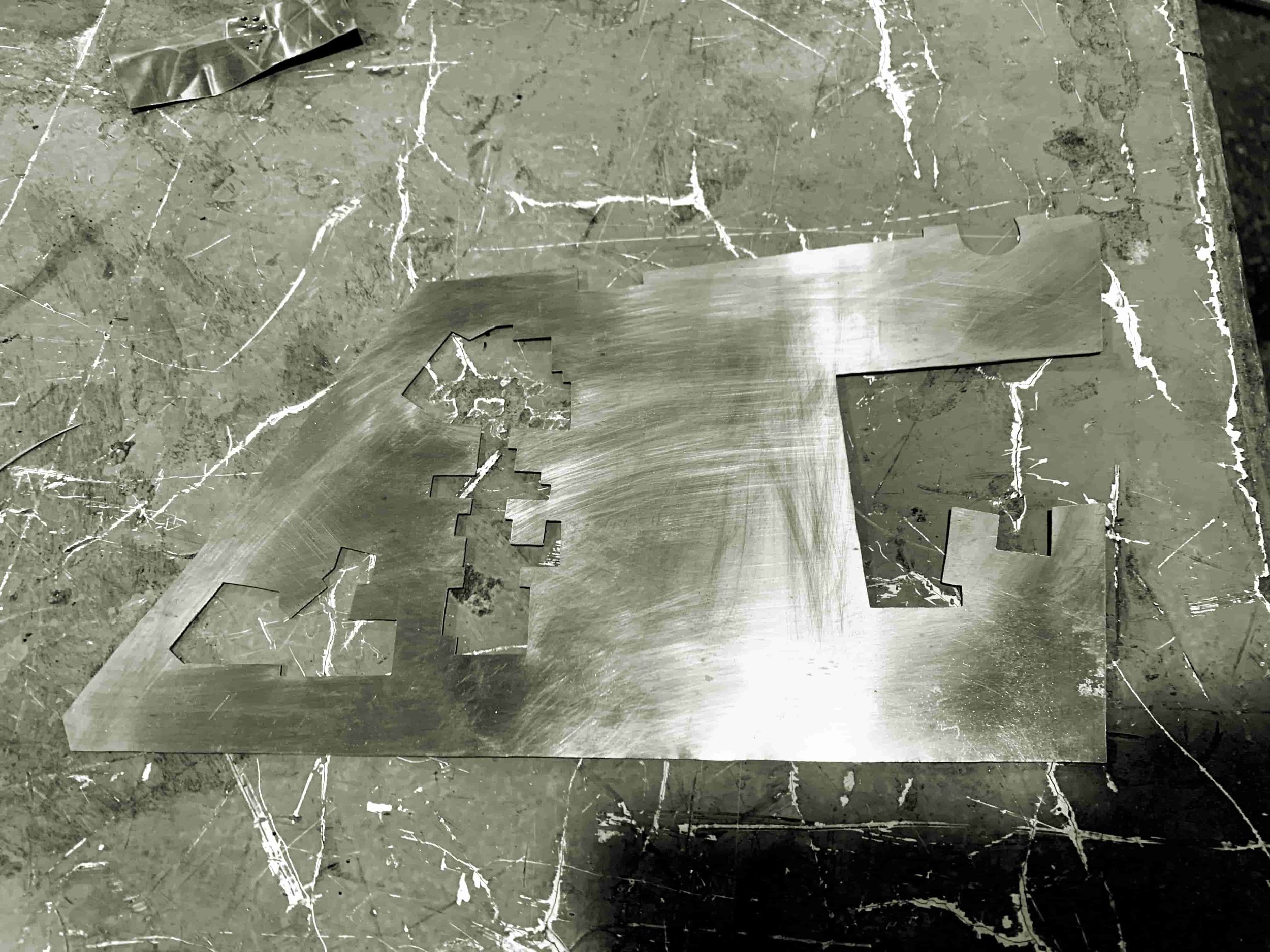

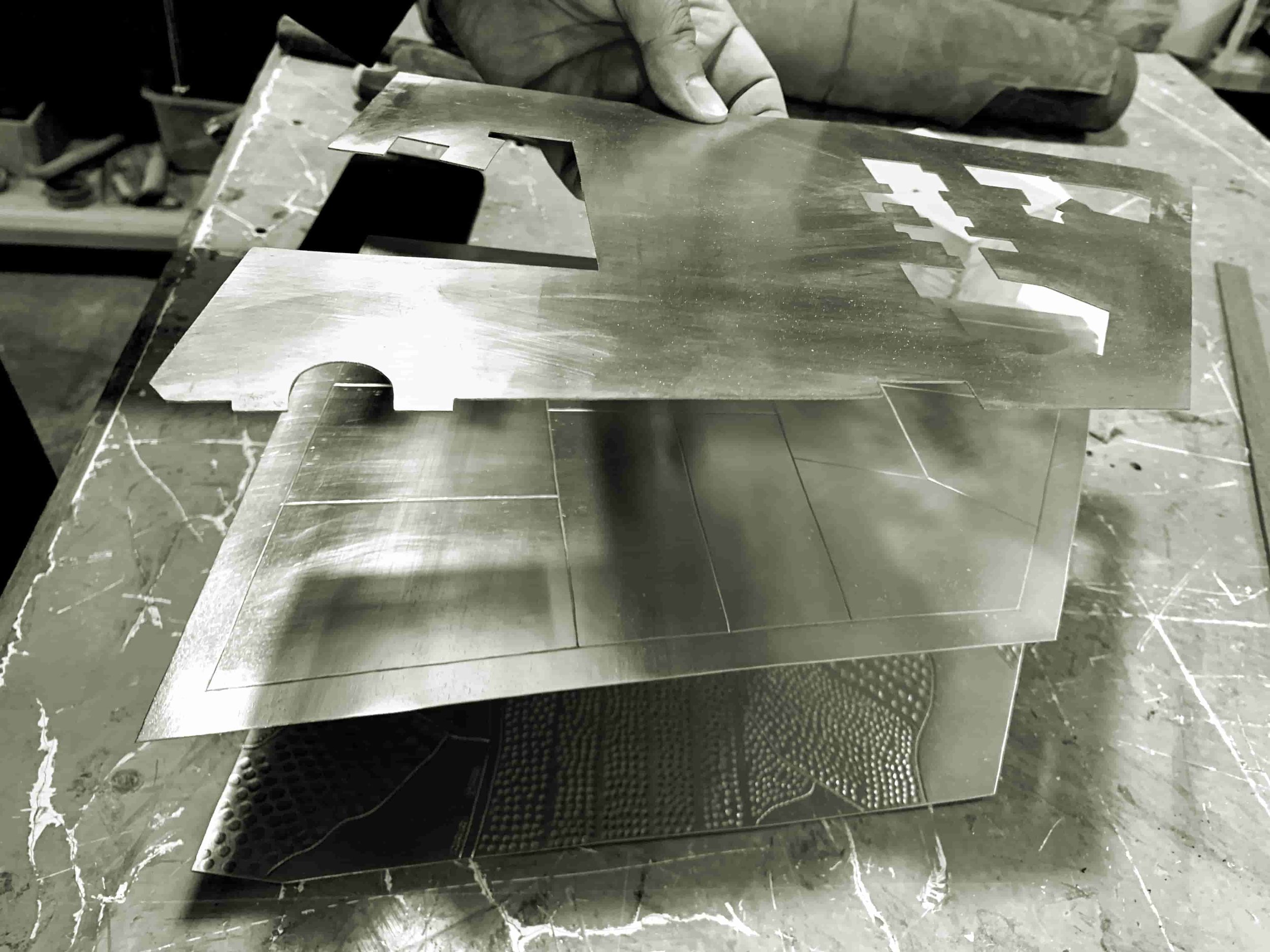

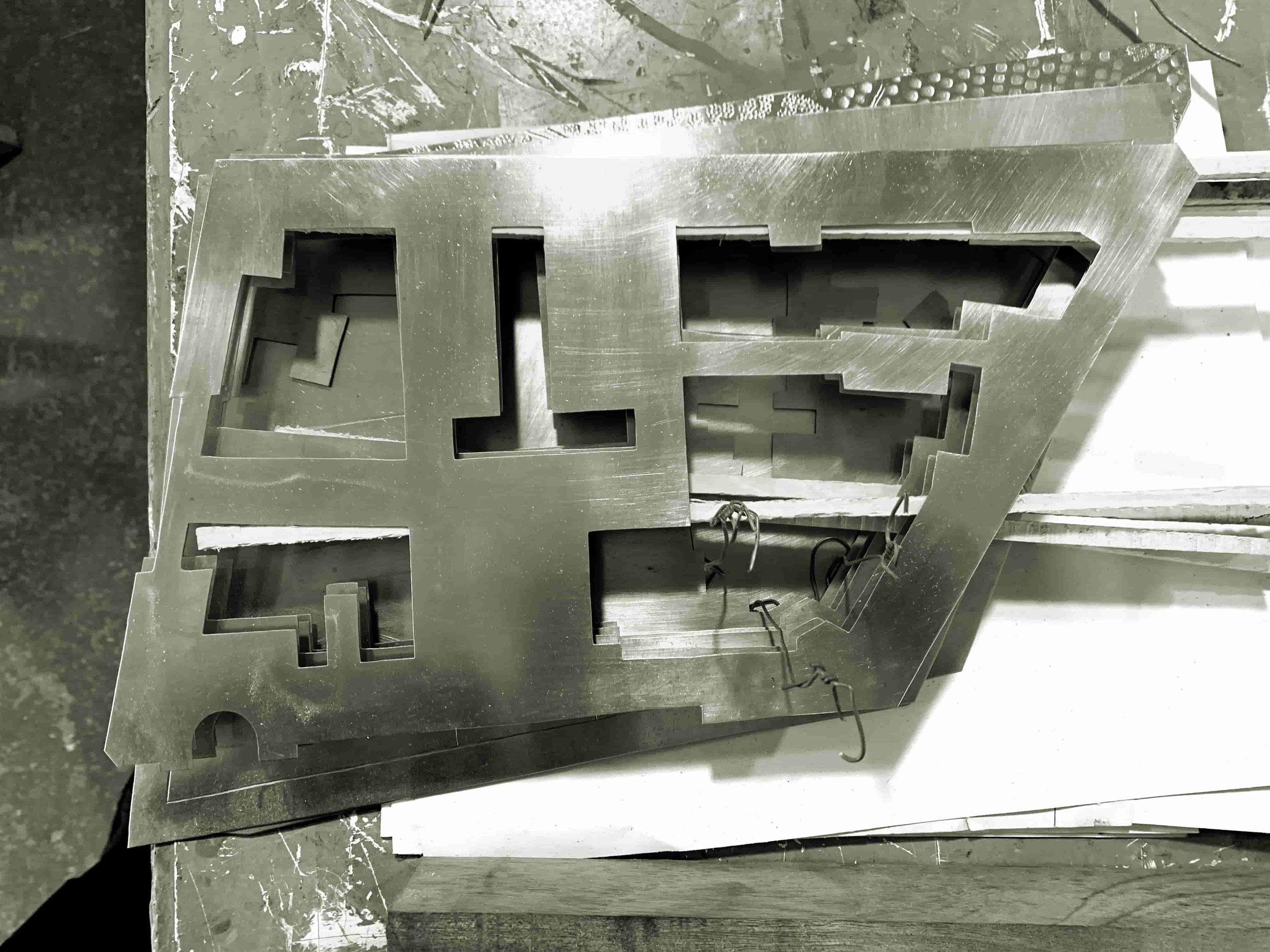

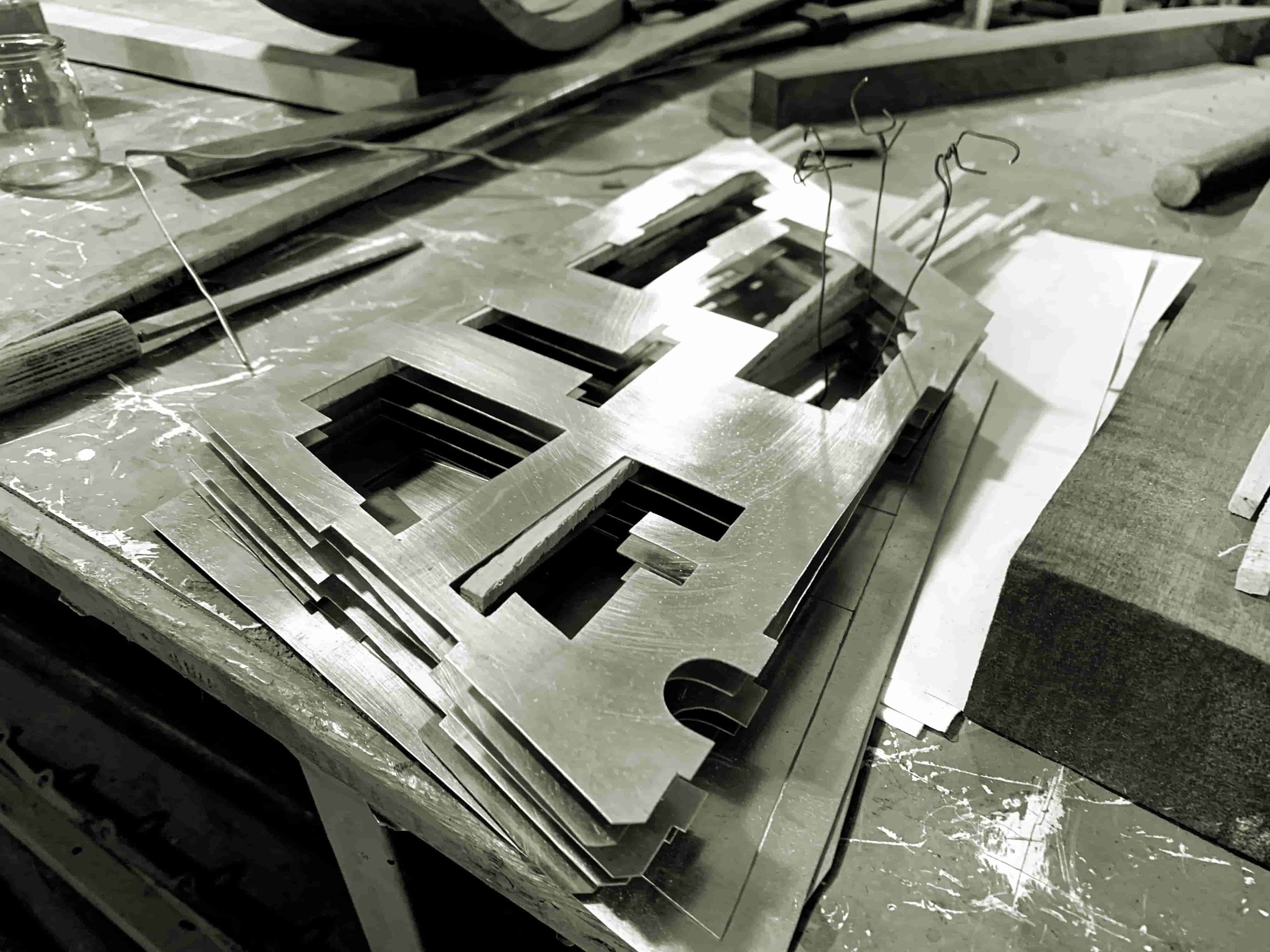

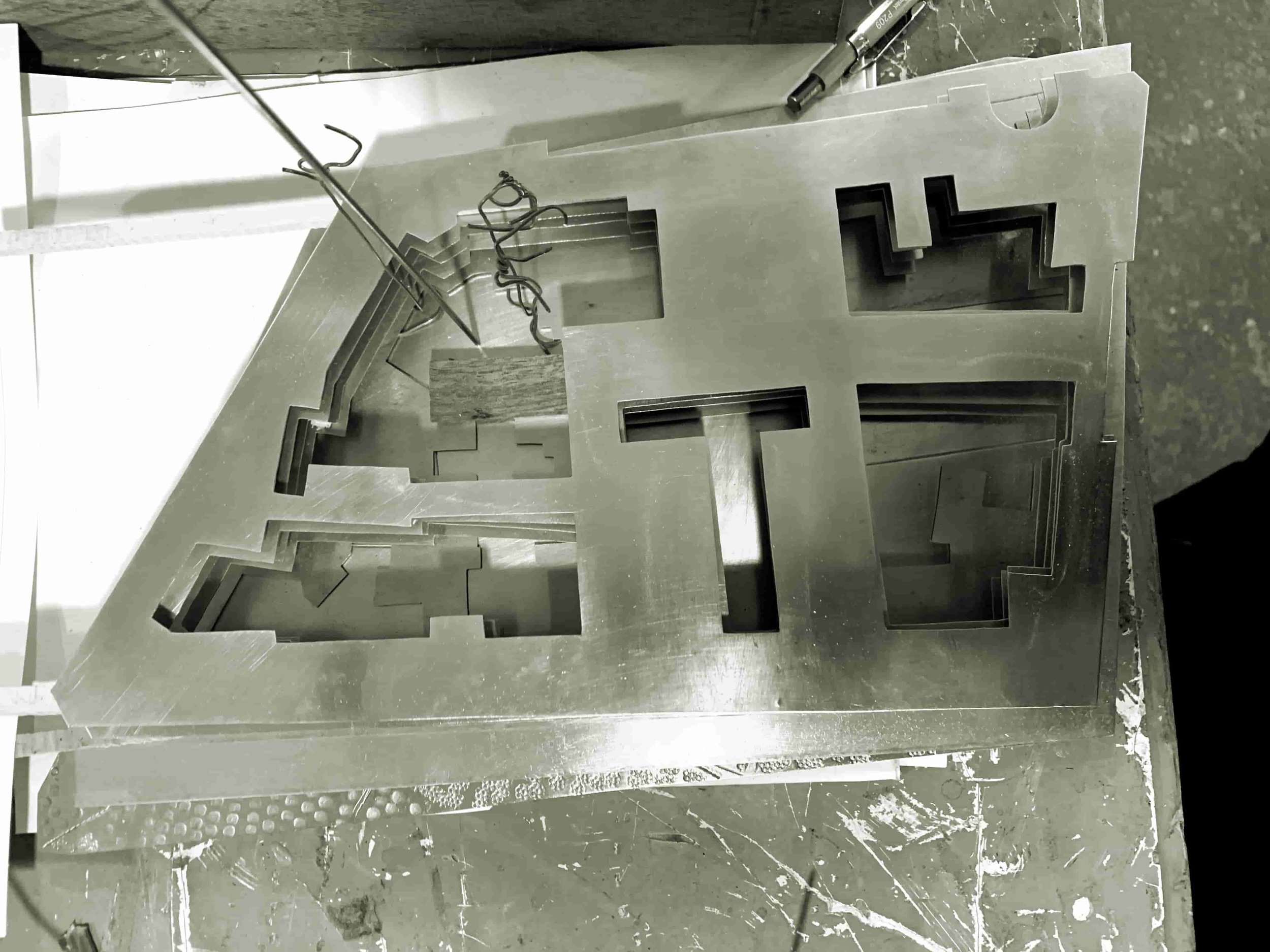

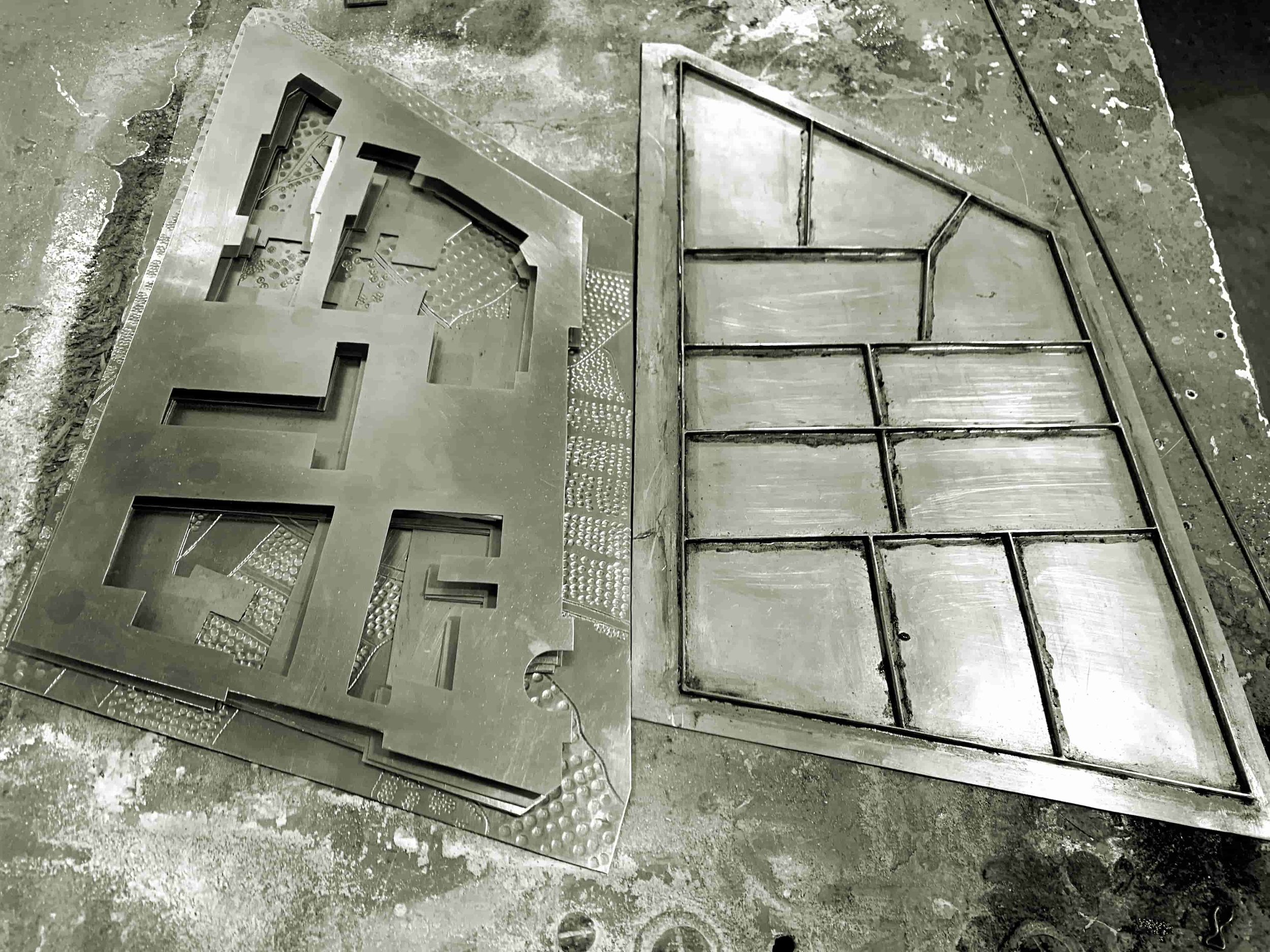

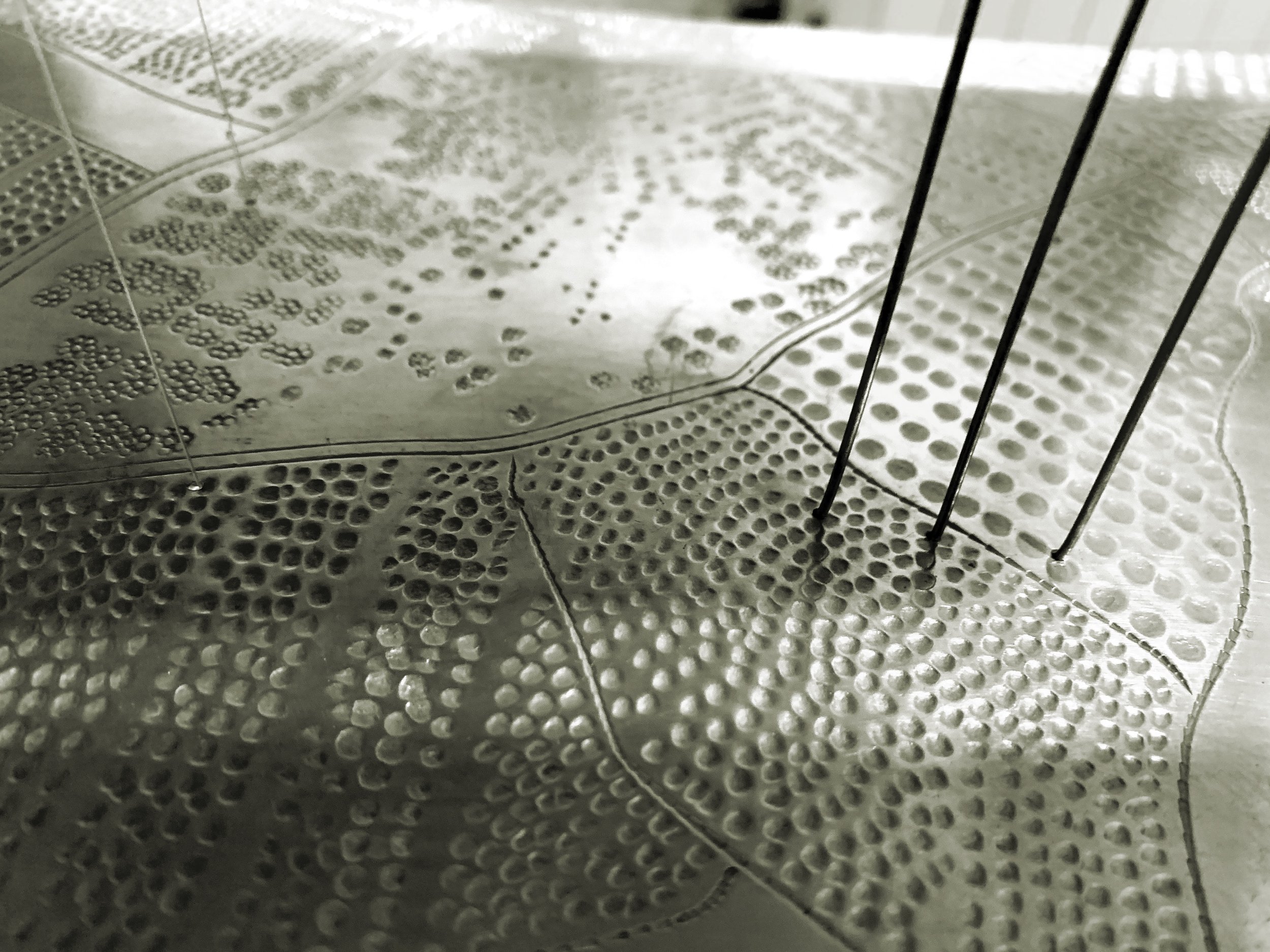

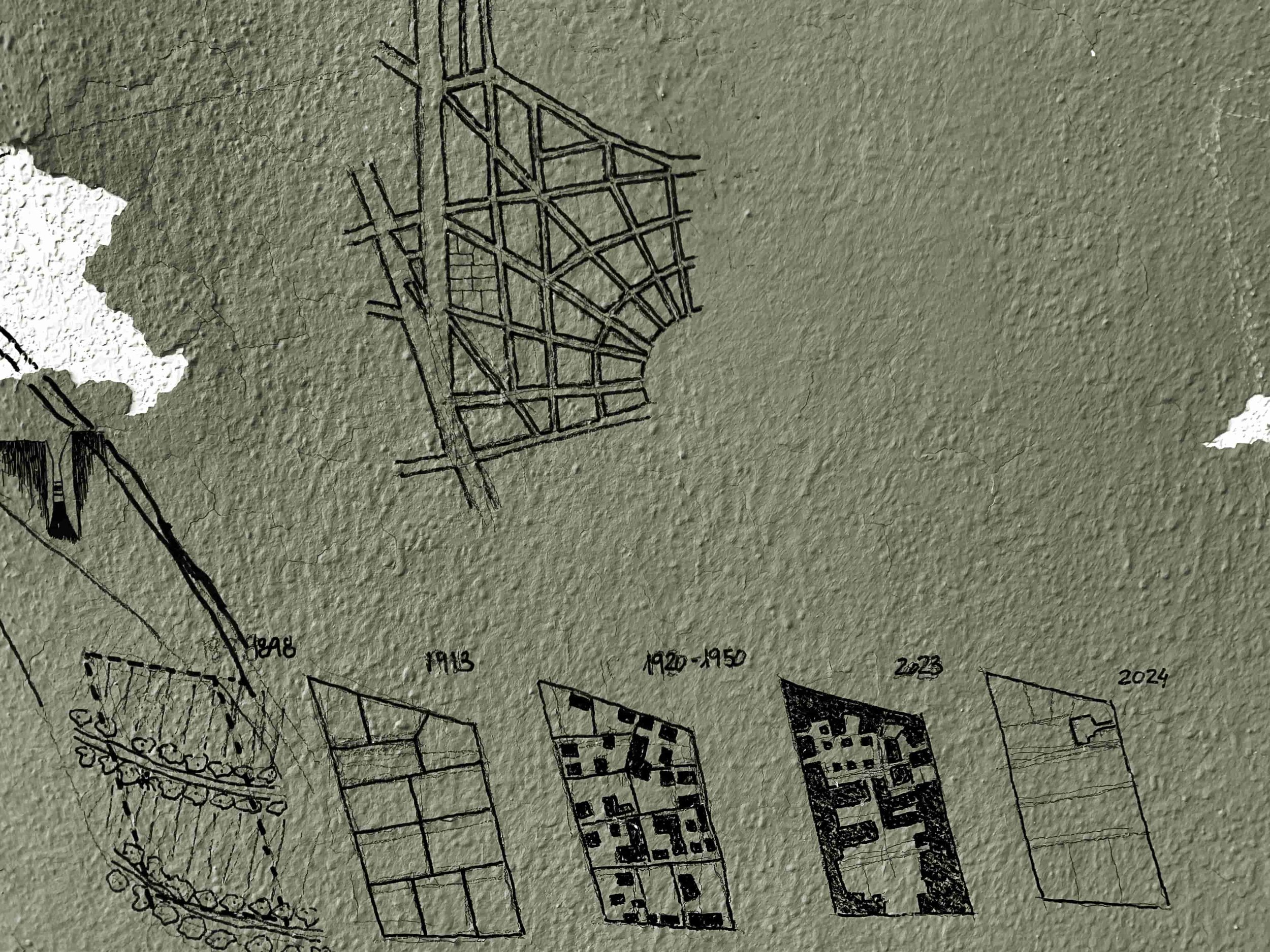

We have established three phases of the history of the city of Marrakesh, the oasis between 1070 and 1898, the cadastral plan of 1913 and the current state. We took as a premise that we needed a simple representation and using the cartography we had. The surface of the model was going to correspond with the urban block in which our plot is located.

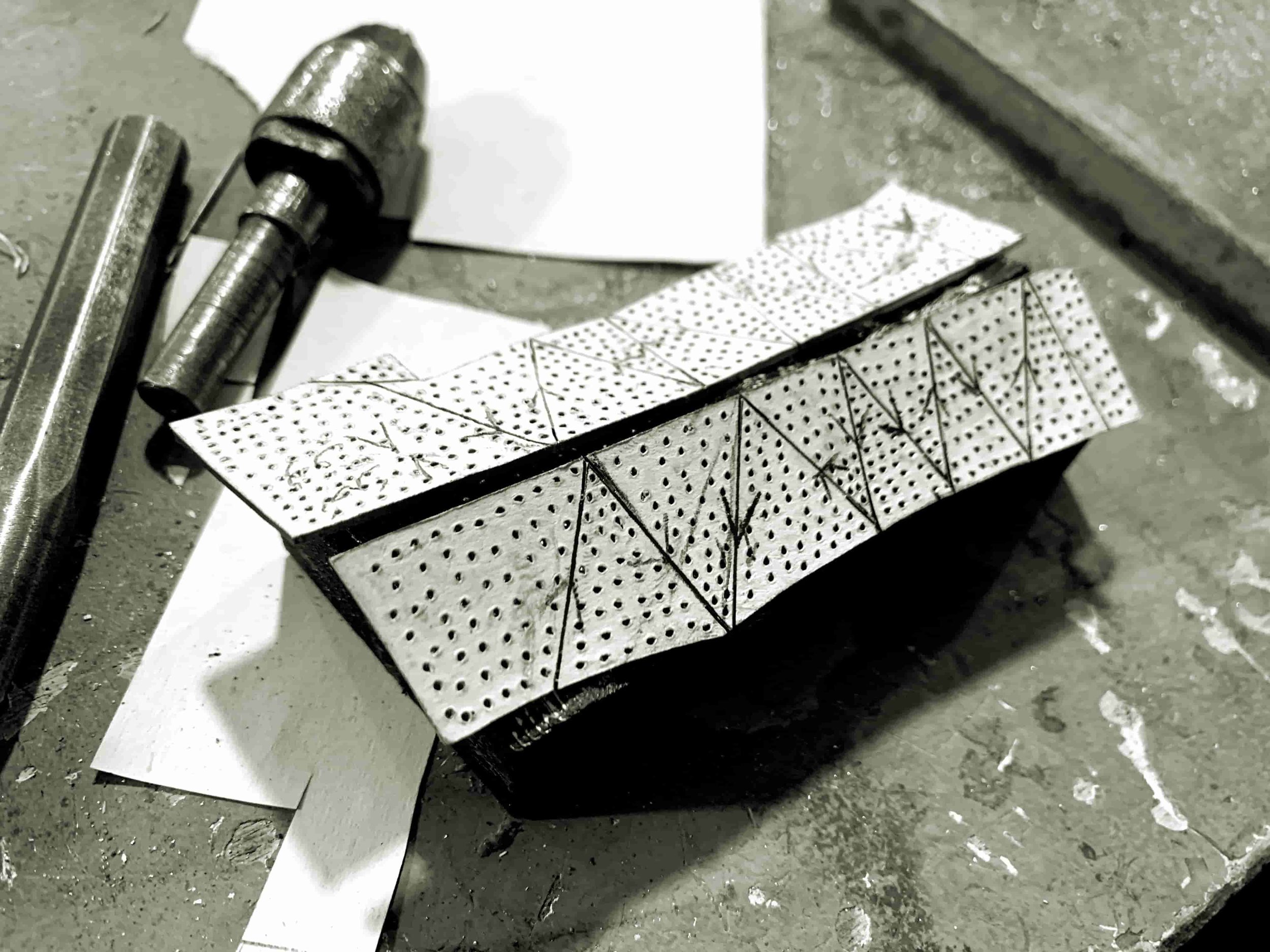

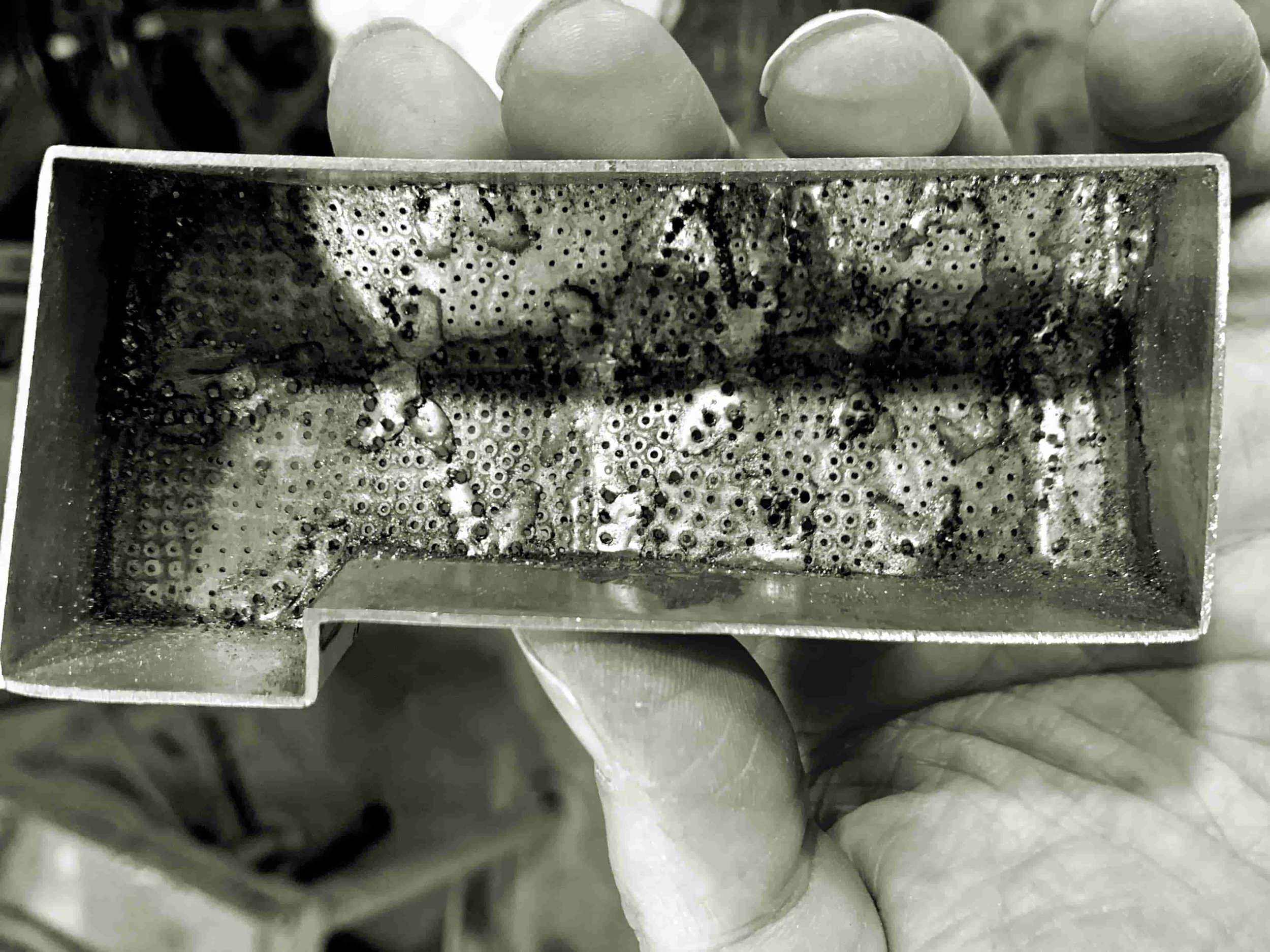

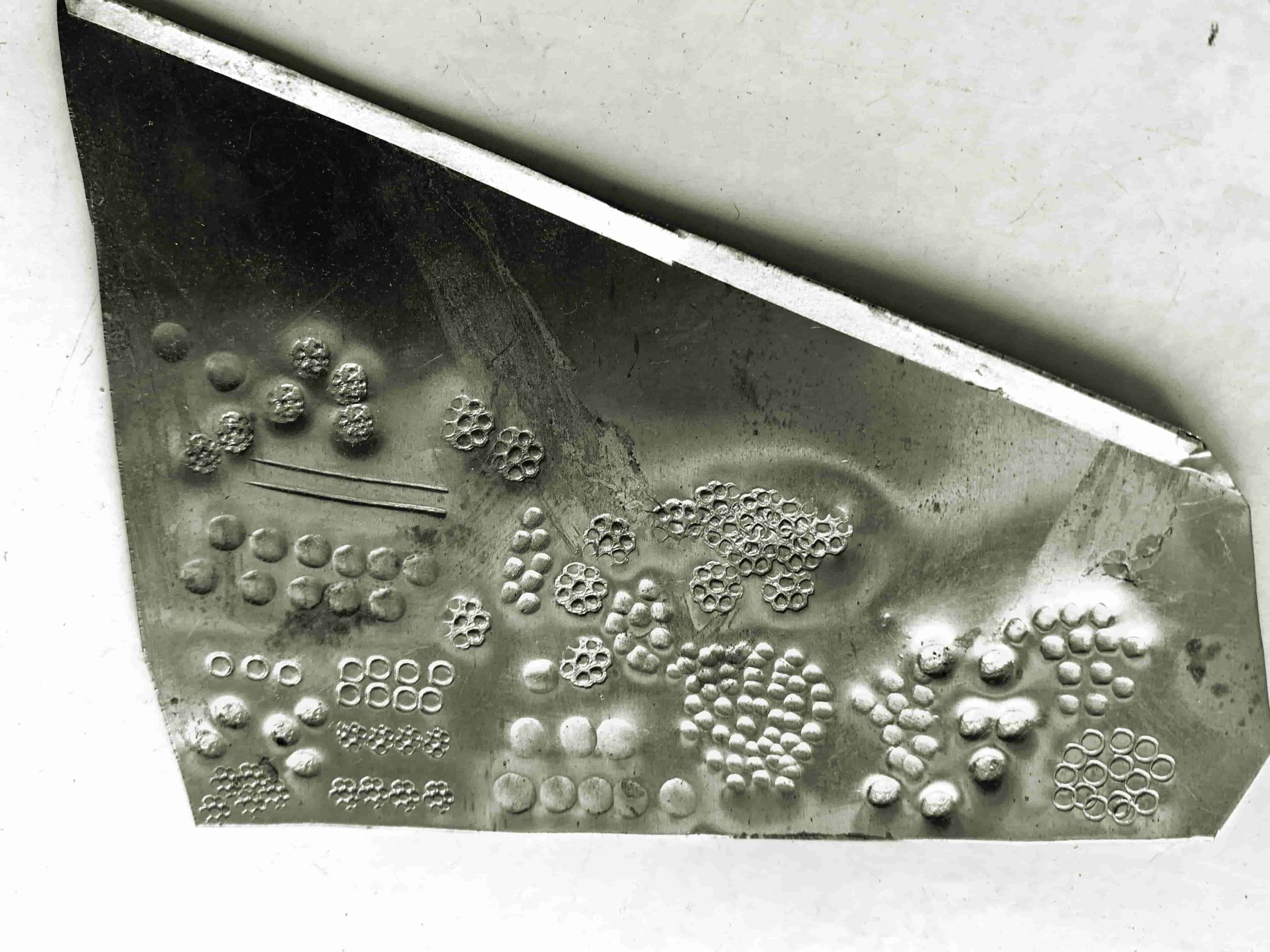

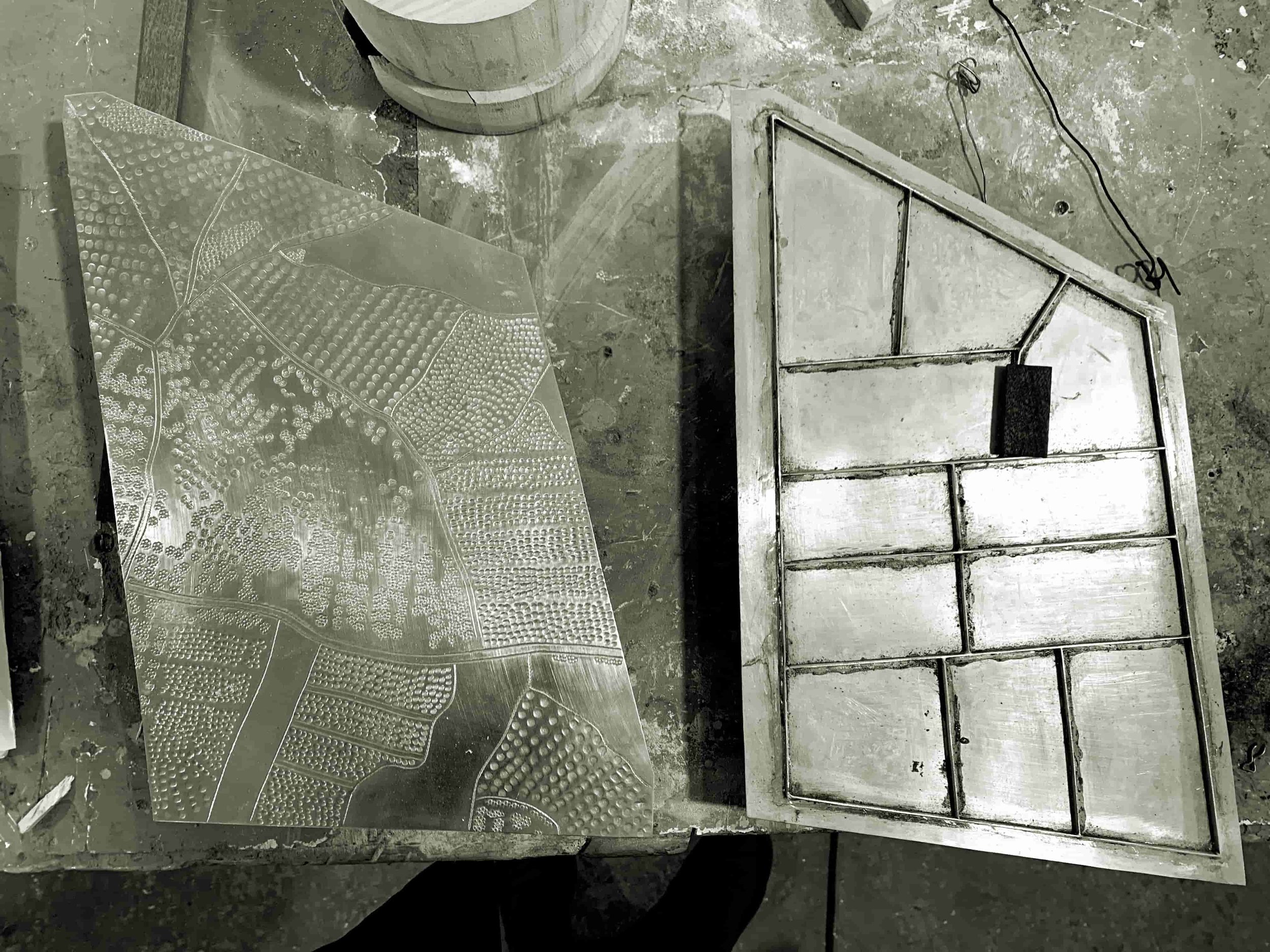

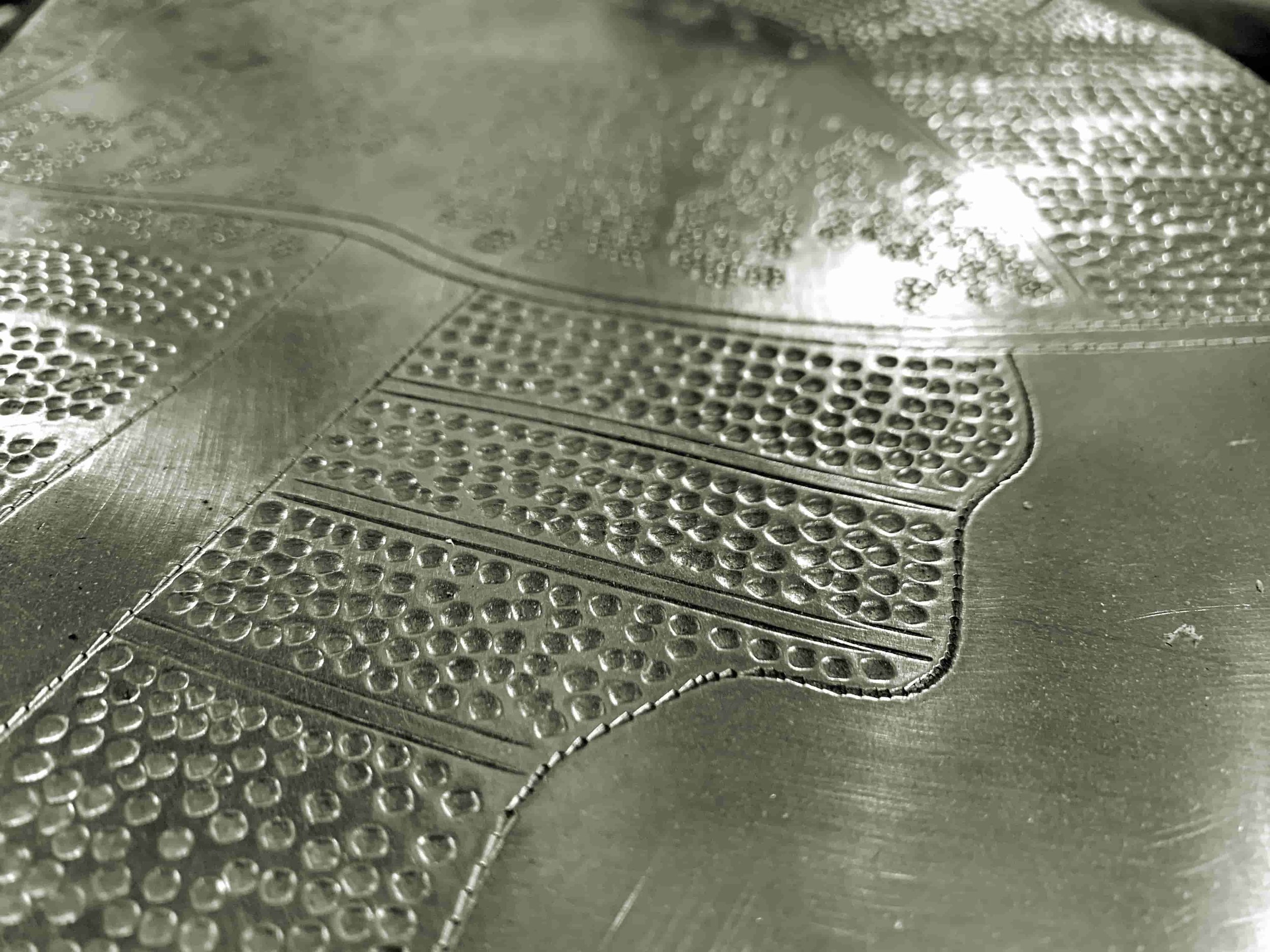

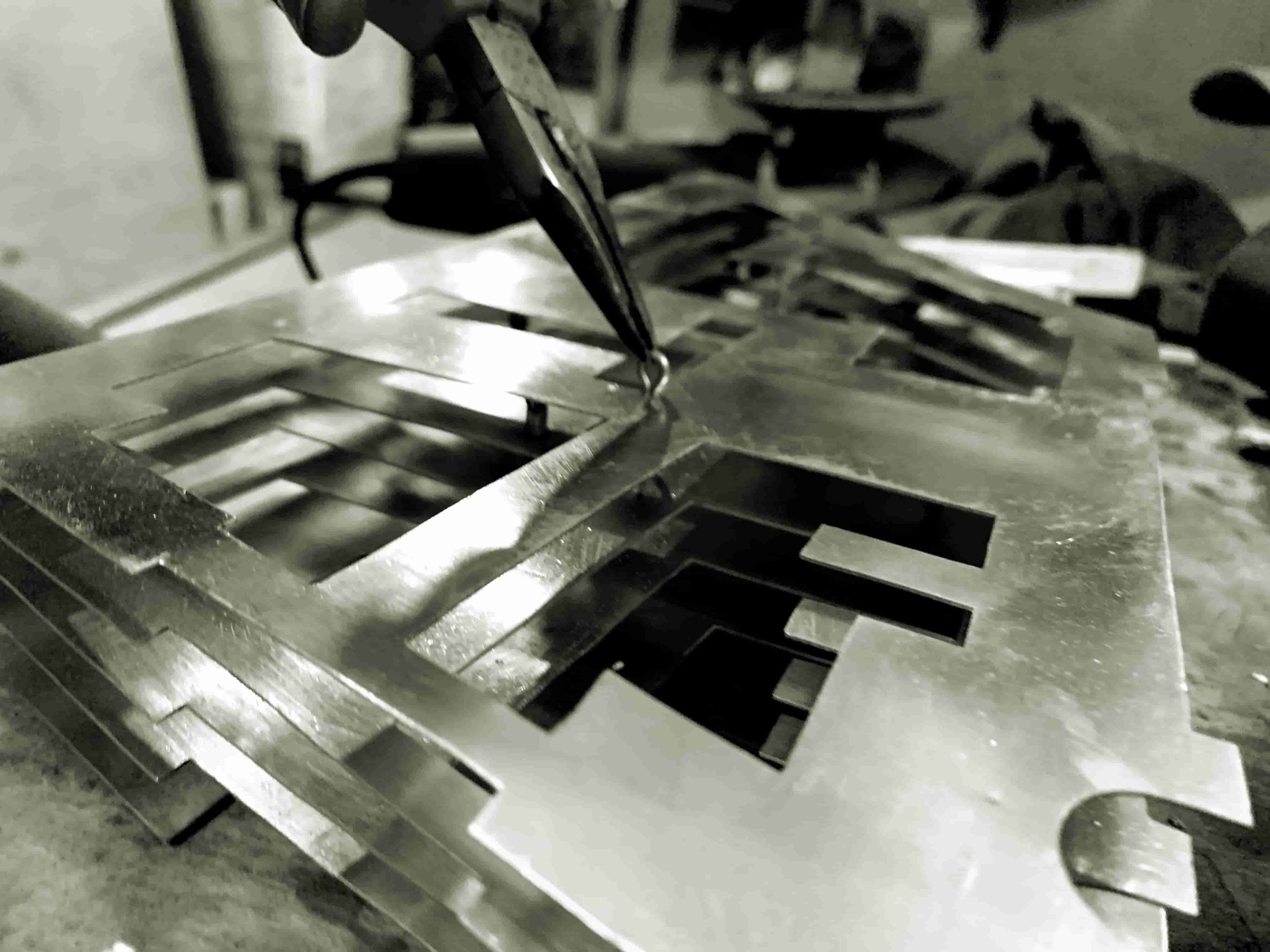

For the first phase it was necessary to indicate the paths that gave rise to the geometries of the plots and the type of tree and cultivated that had inside based on an image of agricultural plots in the surroundings of Marrakesh. Hassan showed us the tools he uses and the mark they leave on a copper plate. He could make circles of different sizes, which allowed us to represent various trees.

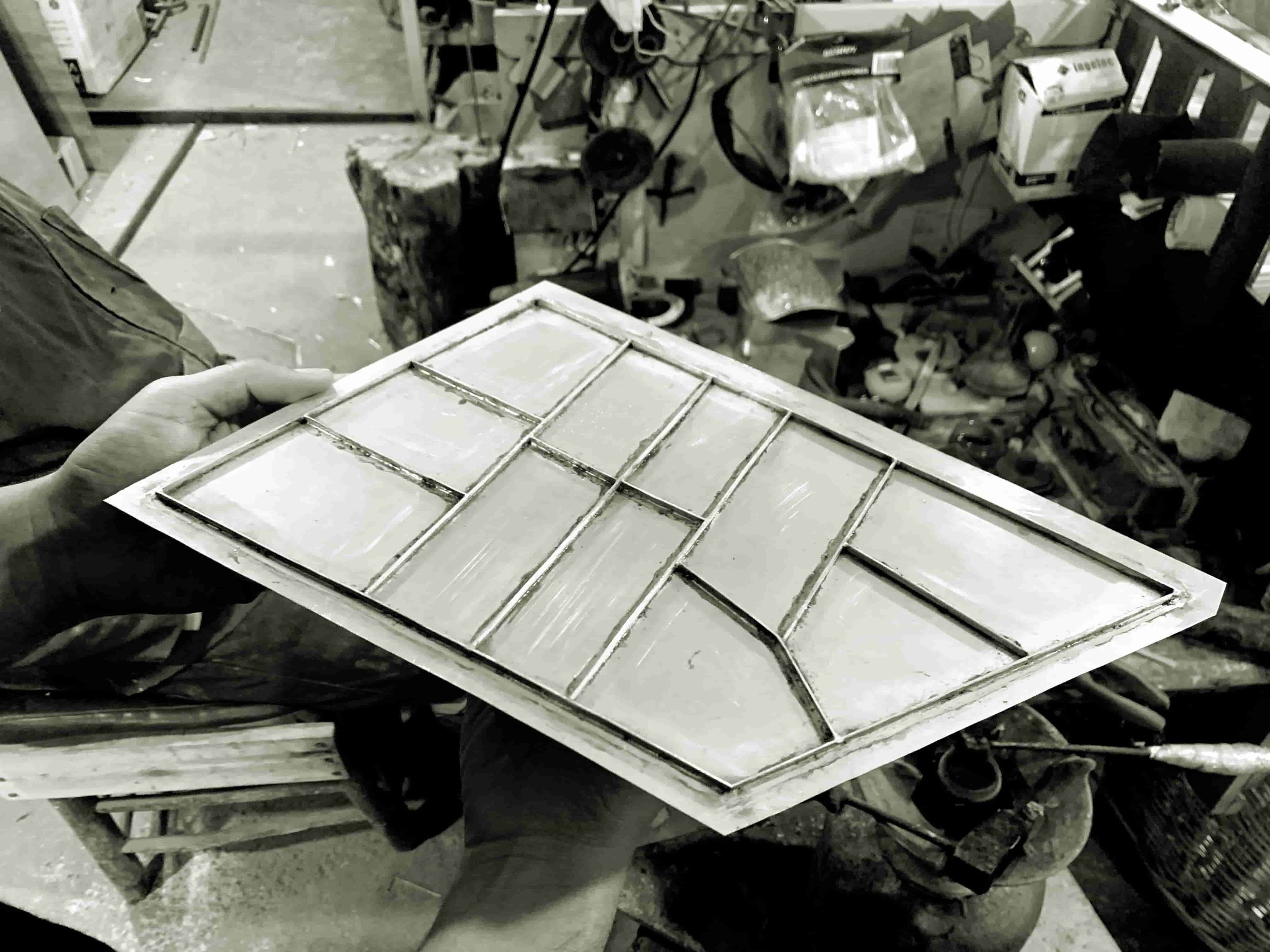

We tested by marking the division of the cadastral plan of 1913 in copper in the same way Hassan had done for the paths of the oasis, but we risked not fully understanding the result. We told ourselves to try as if the plots had walls in their perimeters and the effect was clearer.

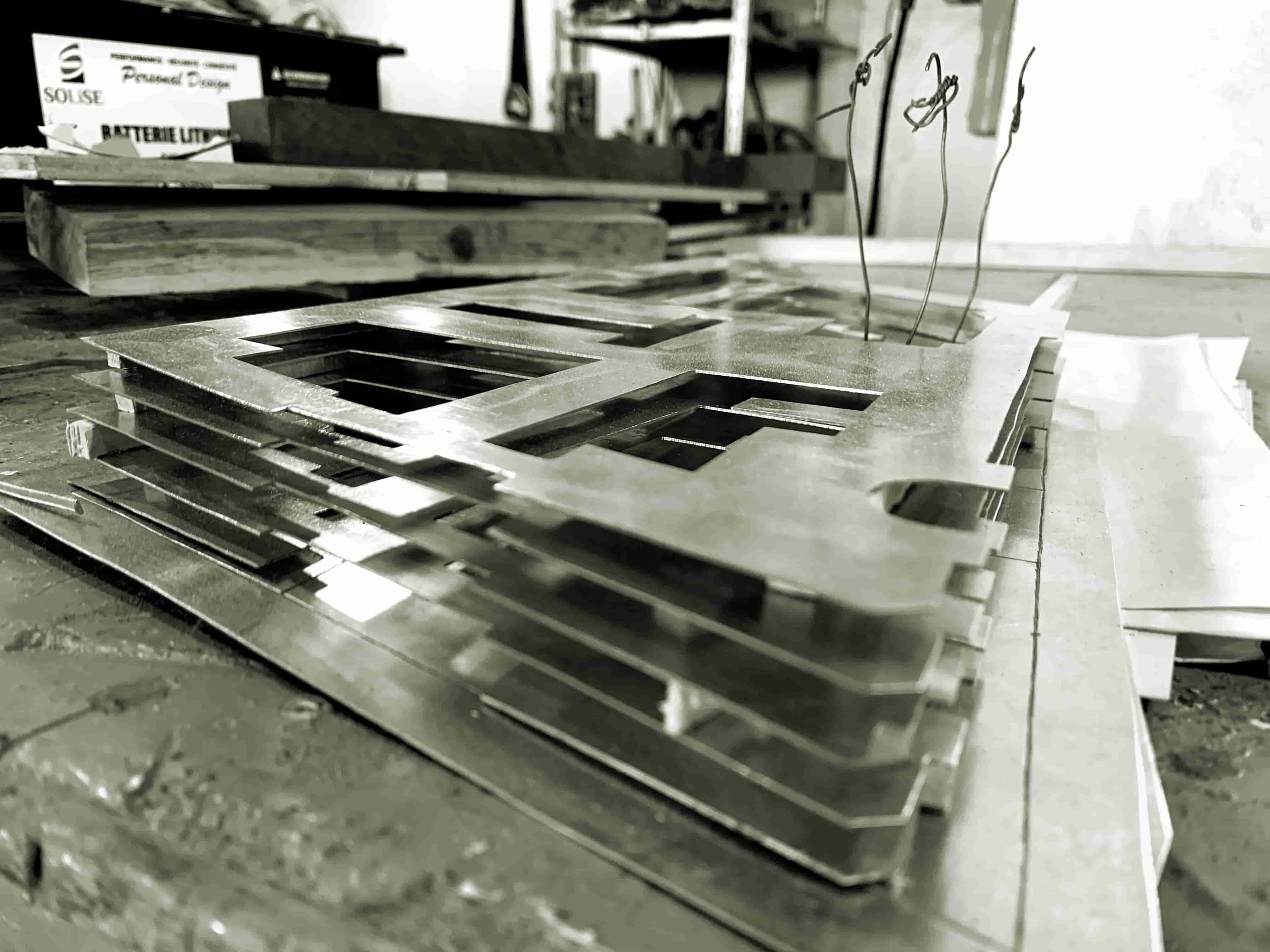

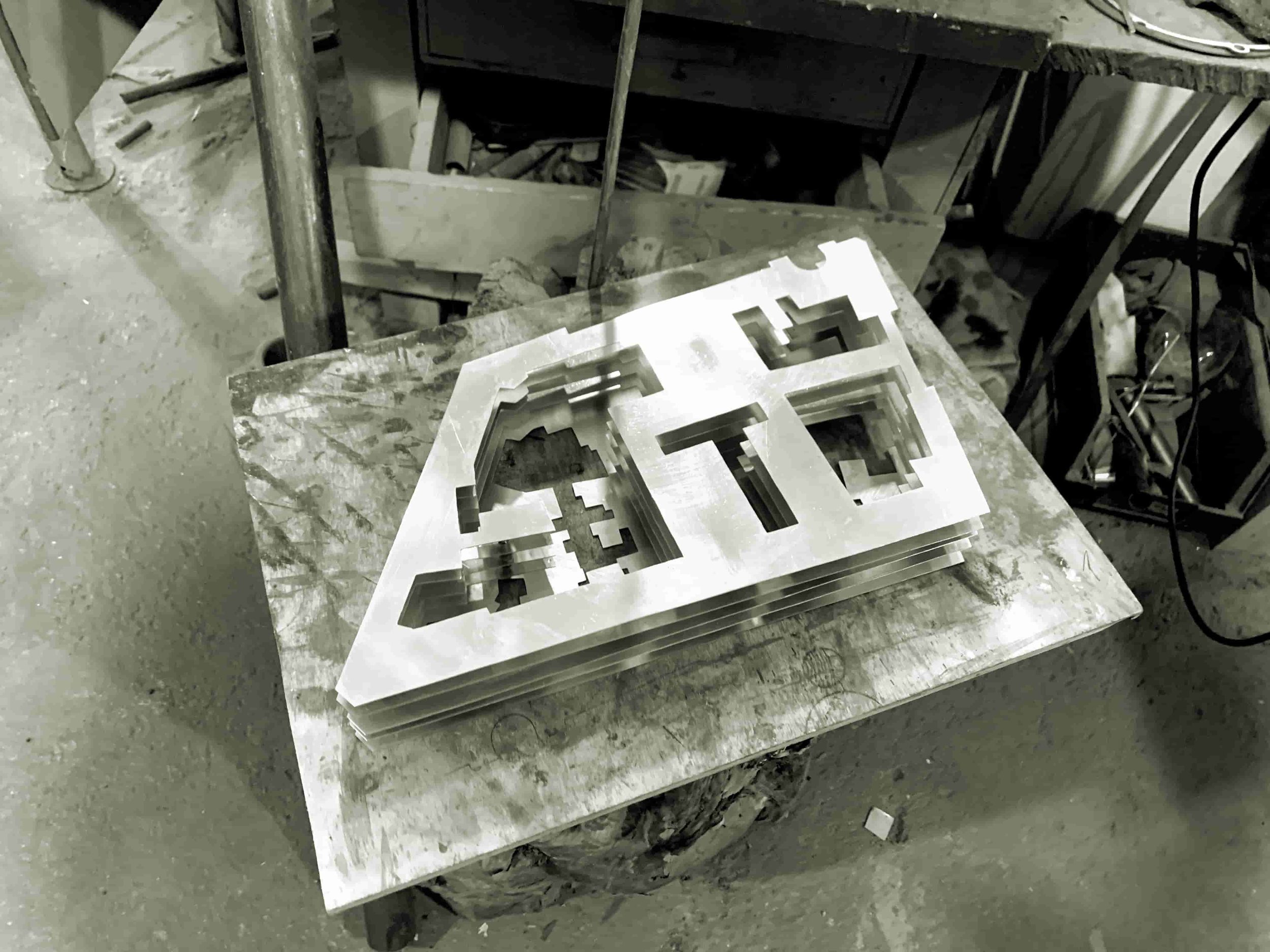

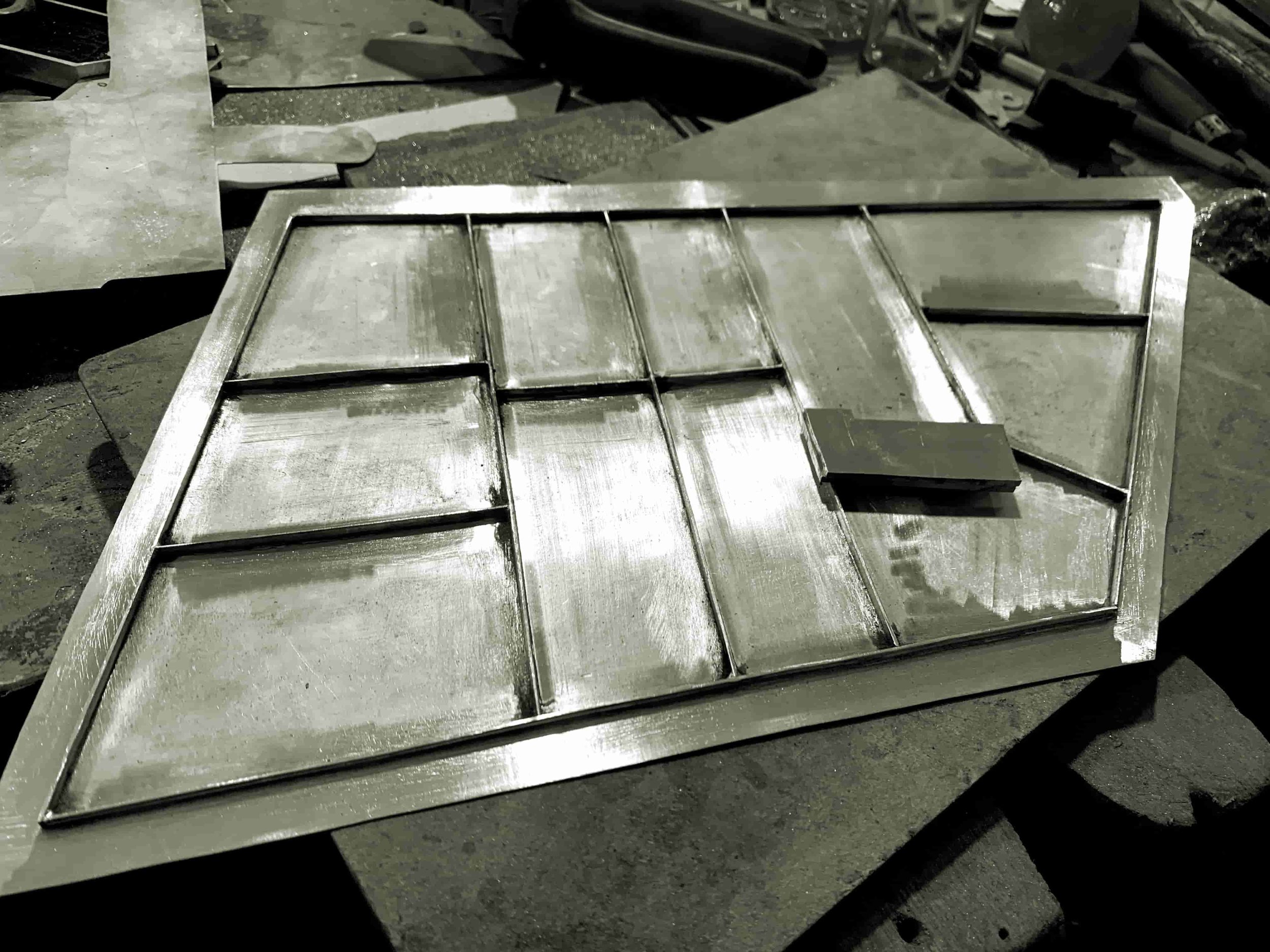

The last phase was more complicated. We needed copper volumes to represent the new buildings, but this massiveness was contrary to the purpose of superimposing suspended plates. However, we did not know very well if by using the copper plates, we were going to be able to show the void inside the urban block. We tested the use of several plates as if they were the slabs of the buildings, approaching them enough to keep their independence but being part of a whole. It was a more coherent solution with the other phases, but it was necessary to resolve how these plates were going to hold and at what distance they were going to be placed. Ismail proposed to solder small cylindrical pieces of copper so that the plates are united. By studying their length and position we could hide them when the model is viewed from different angles.

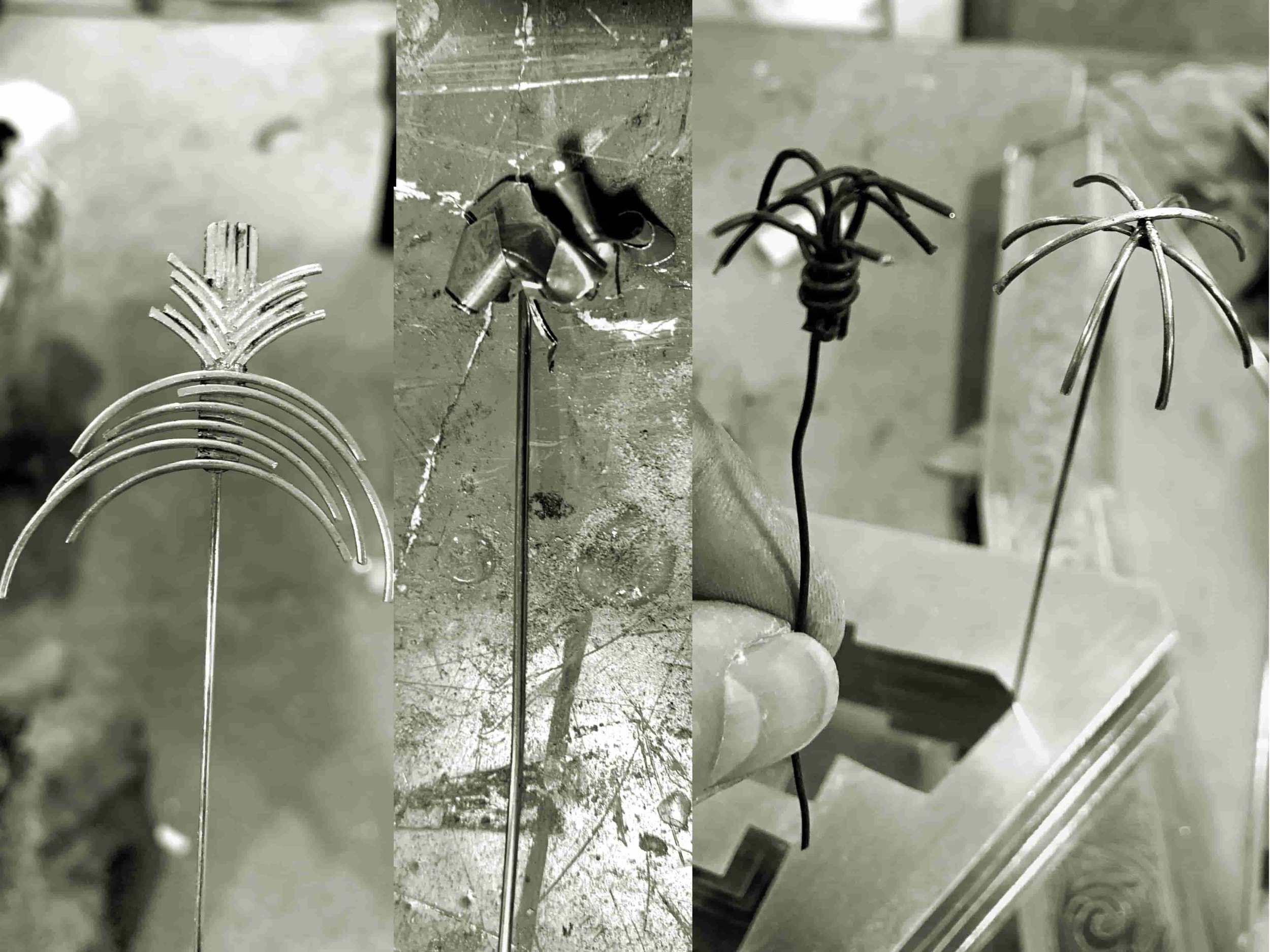

We still had a few questions to solve there; how to visually unite the three phases; how to represent our building and where to place it. We decided that it was important to use palm trees to connect the three evolutionary phases and thus show the main intention of the project, the recovery of the plot's identity as green space. Ismail suggested several types of palm trees and we picked one of them. Regarding the building, we placed it on the cadastral map phase because it was not possible to support it on the upper level (there was no ground level) and hanging it was not an option either.

The model in the exhibition once finished.

It was really a great pleasure to have been able to work with the craftsmen of Fenduq; Abdelghafour Bouktrouk, Abdelkader “Dragon” Hmidouche, Abdelaali Arib, Ismail Bounit, Hassan El-Mouaddine et Mohammed Ouahddou, Samya Abid et Eric Van Hove. In a way, they allowed me to relive moments associated with my childhood since I grew up between warehouses dedicated to construction trades (Comandancia de Obras de Ceuta), where I used to play in the electrical, mechanics, masonry and carpentry workshops. This time, it was not a game but an exercise and reflection linked to the heritage and contemporary architecture of Marrakesh, at least it was an attempt.

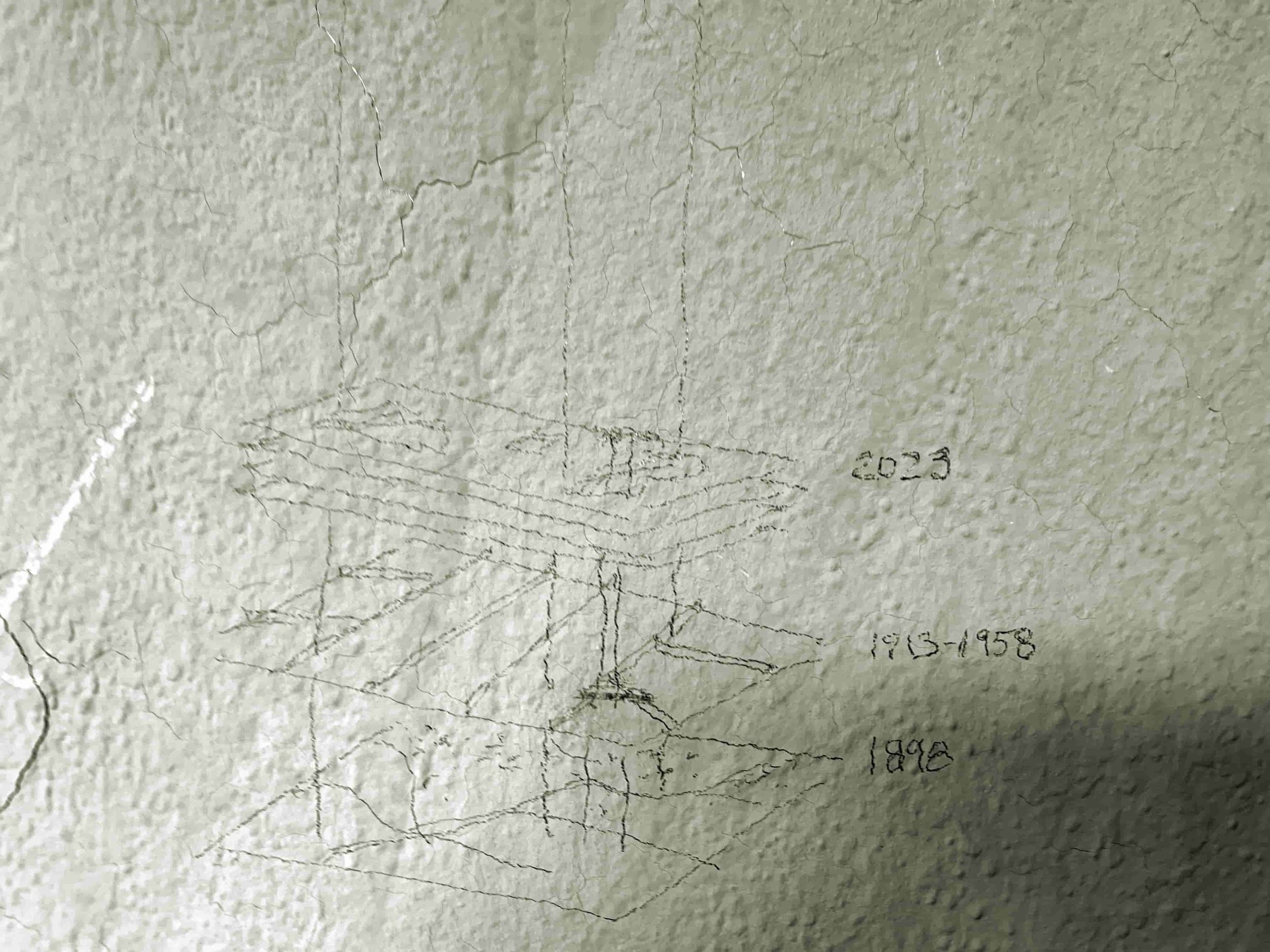

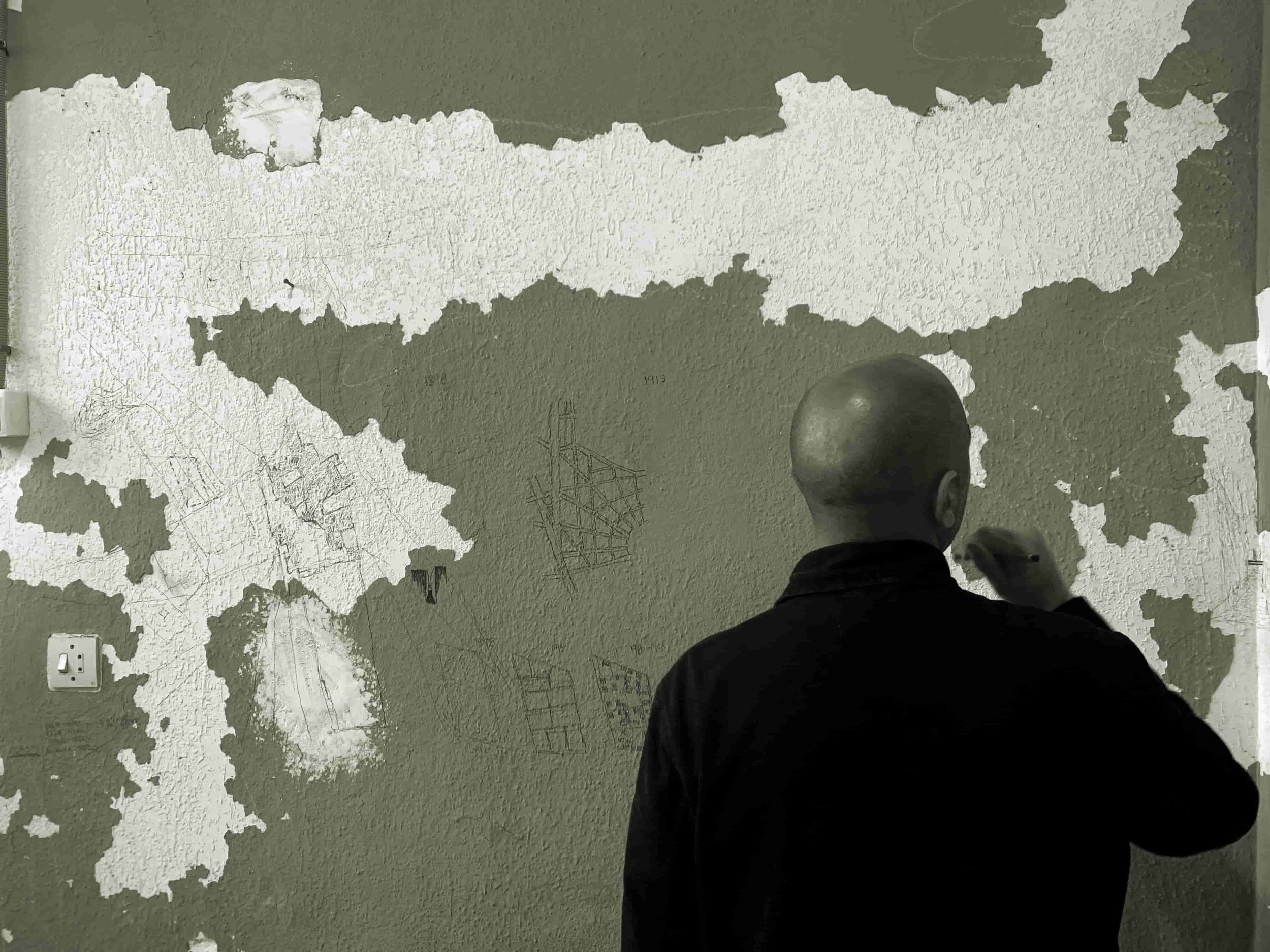

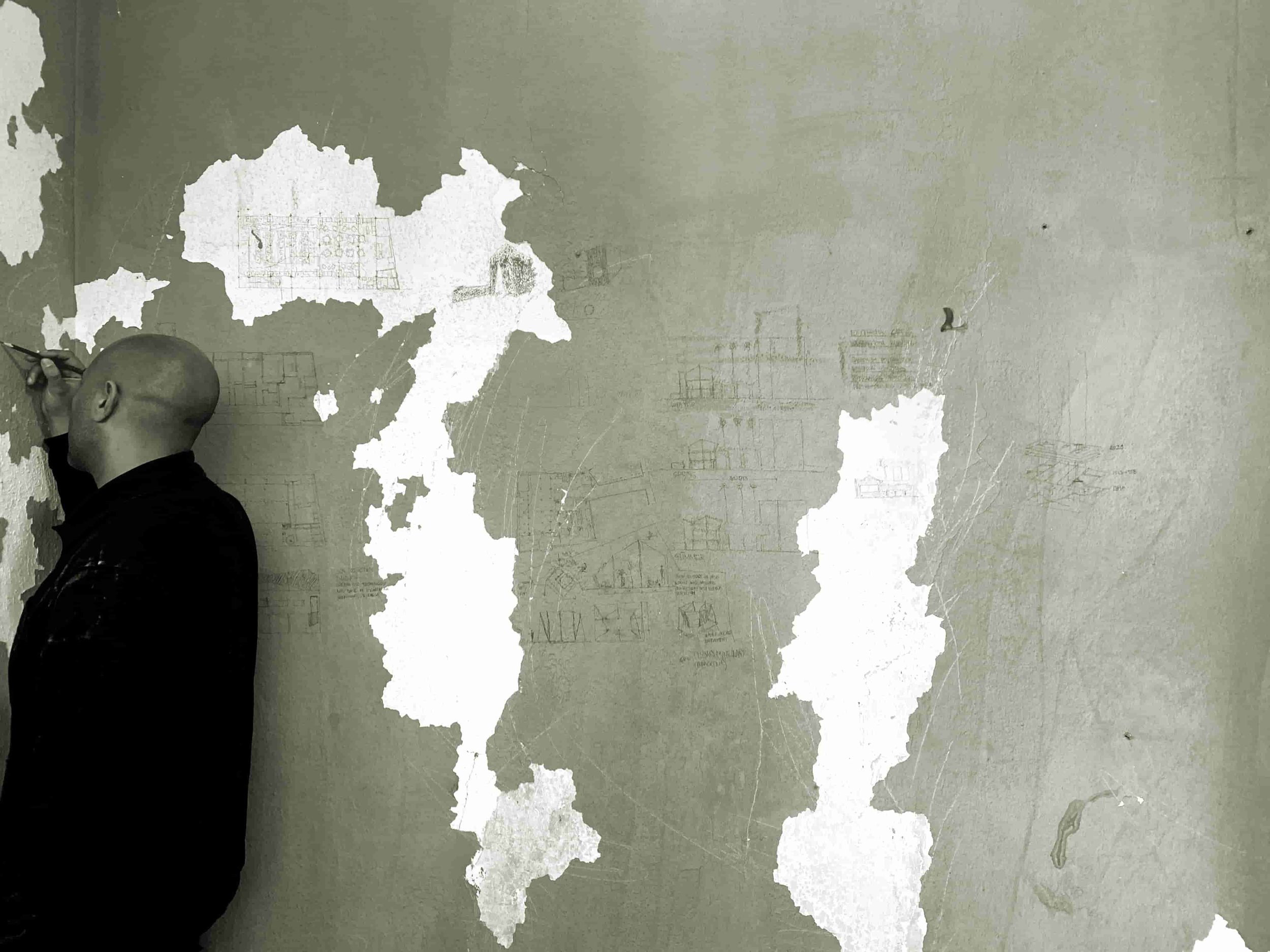

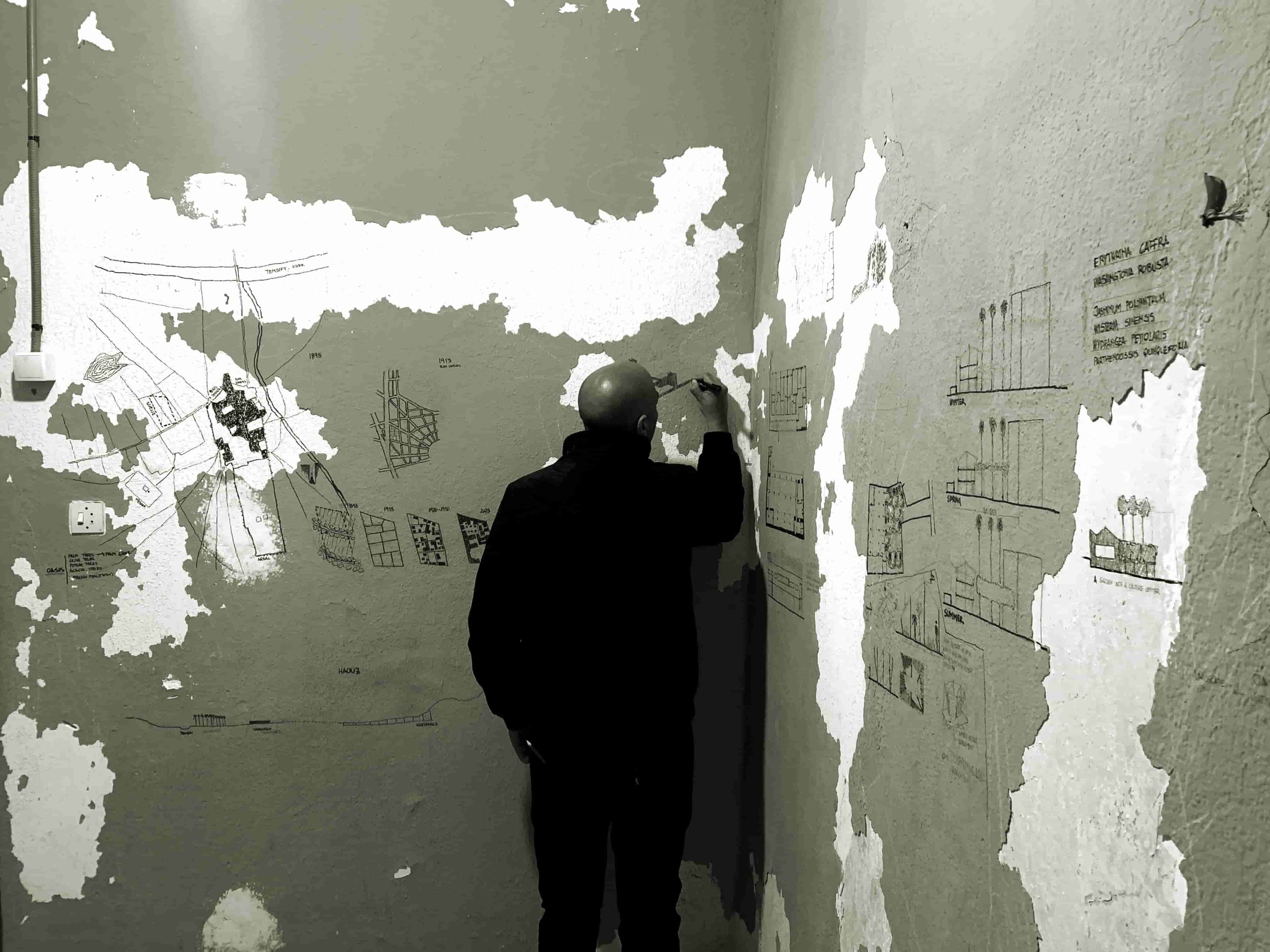

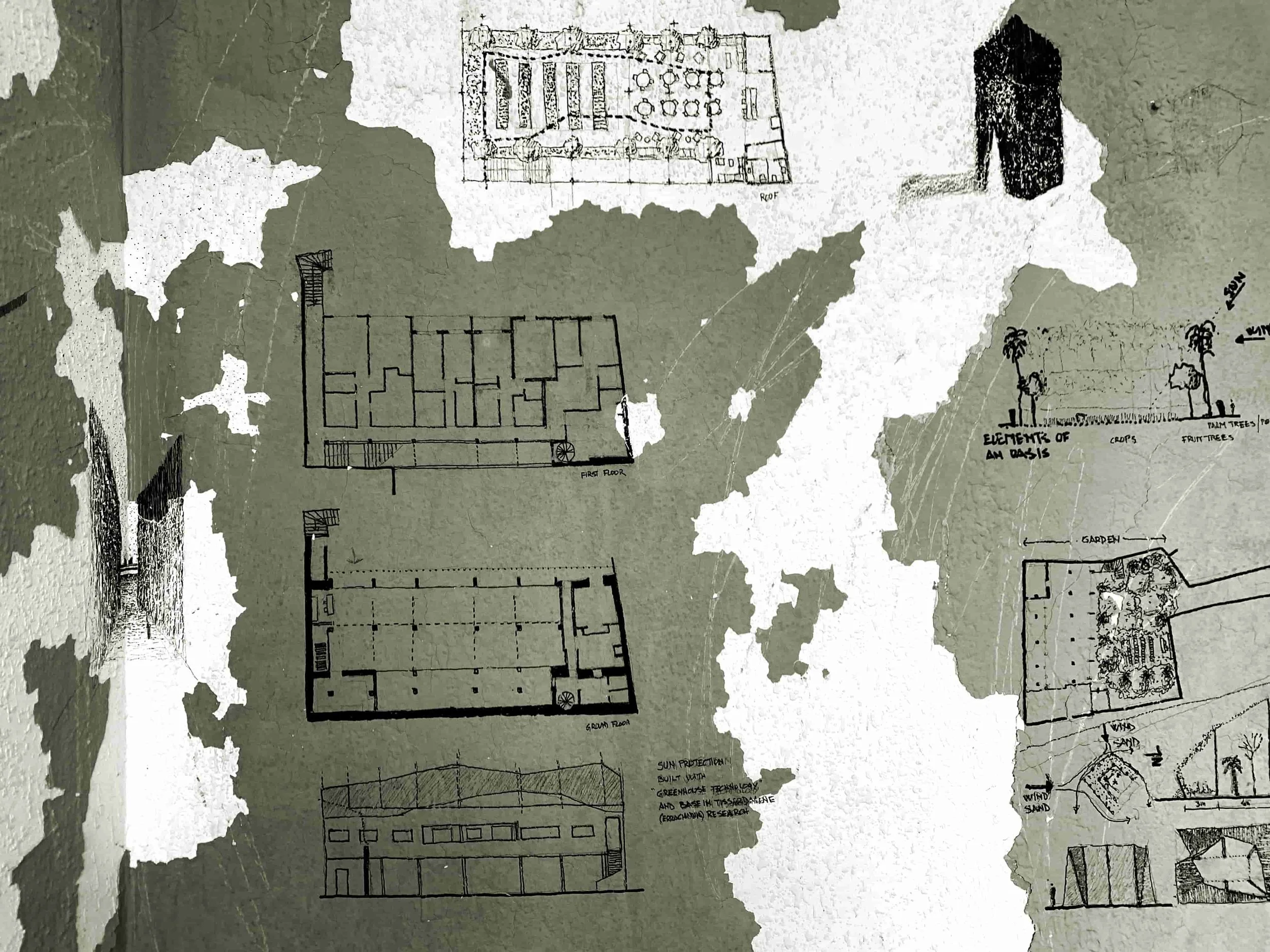

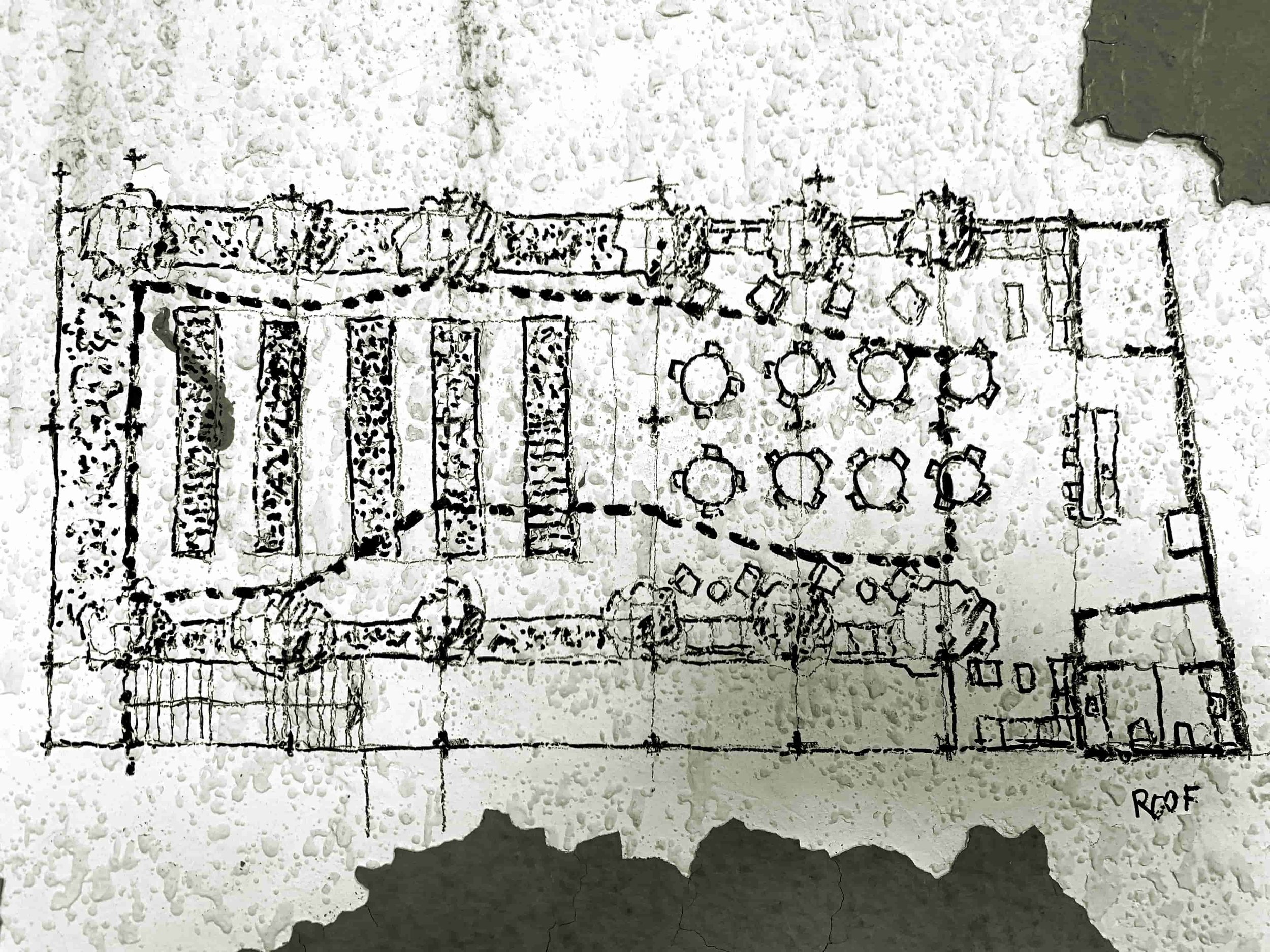

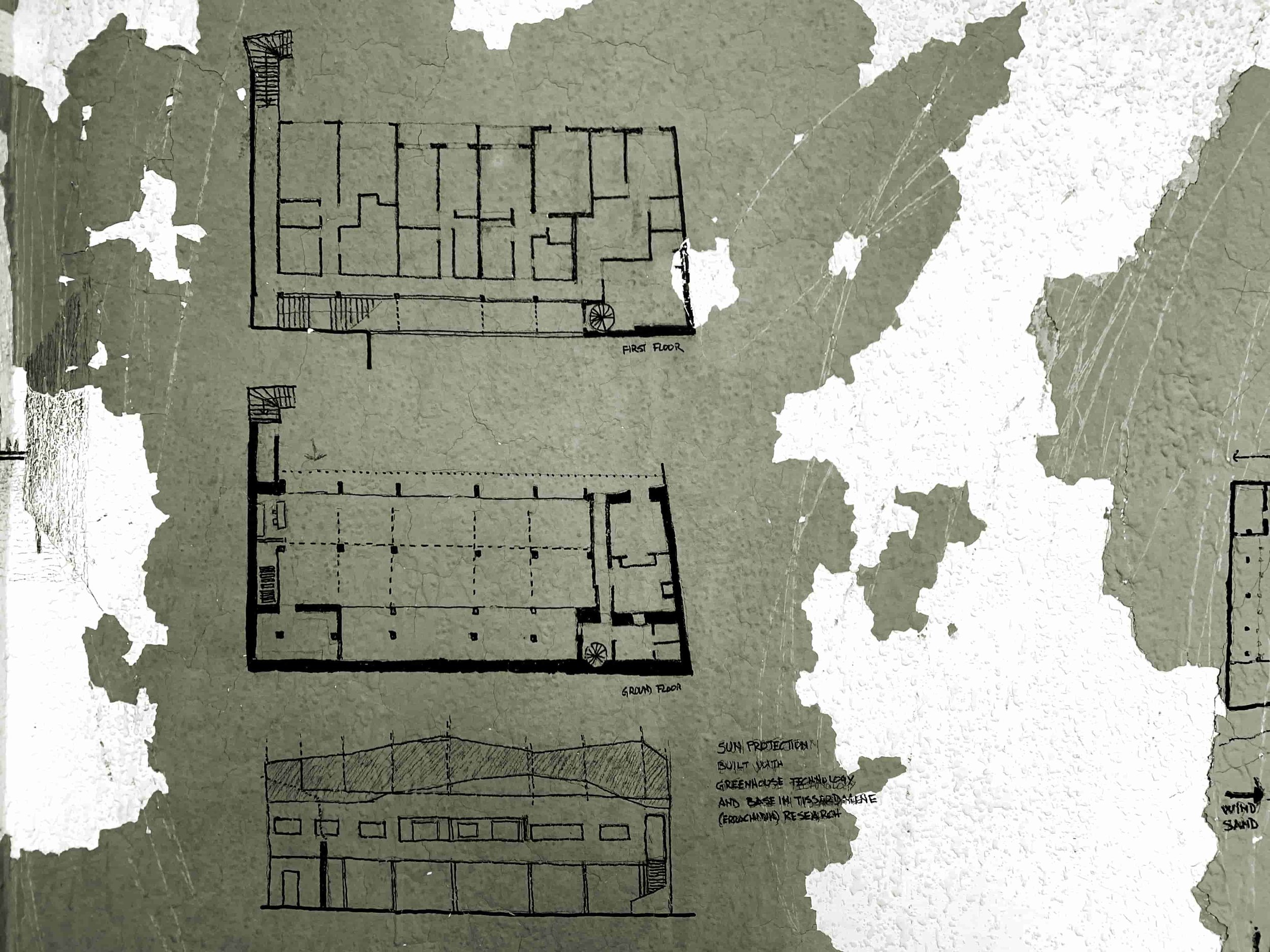

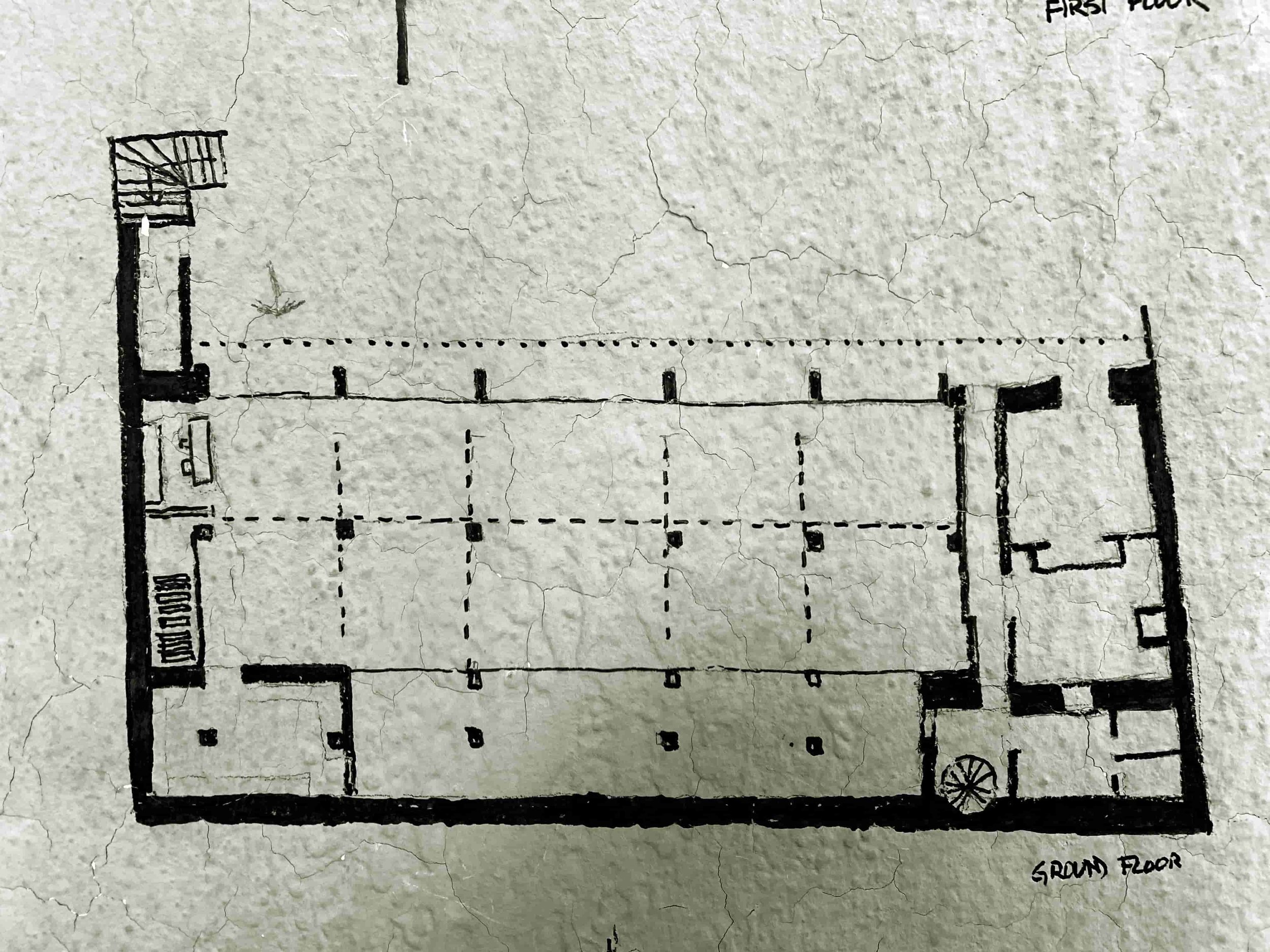

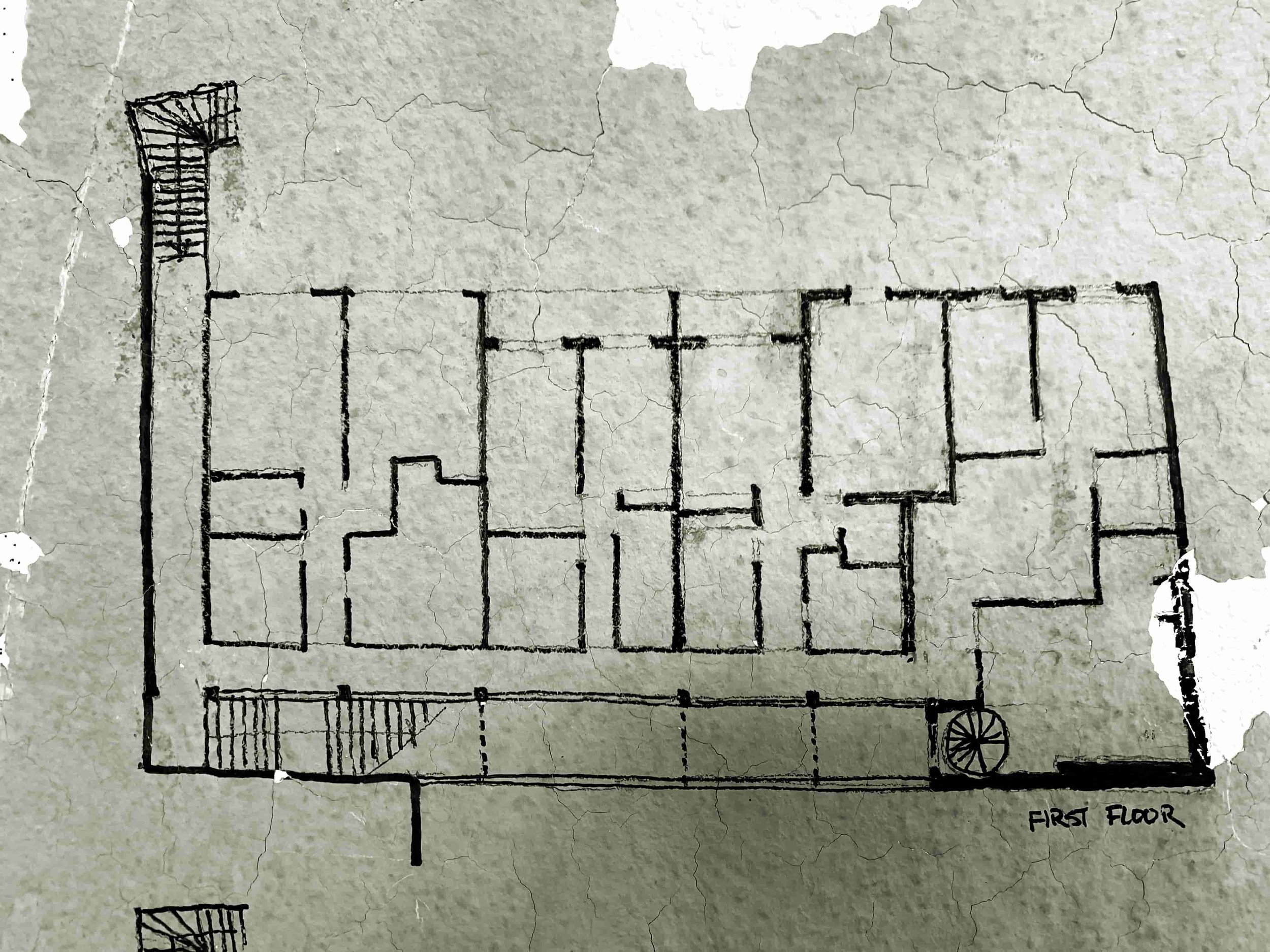

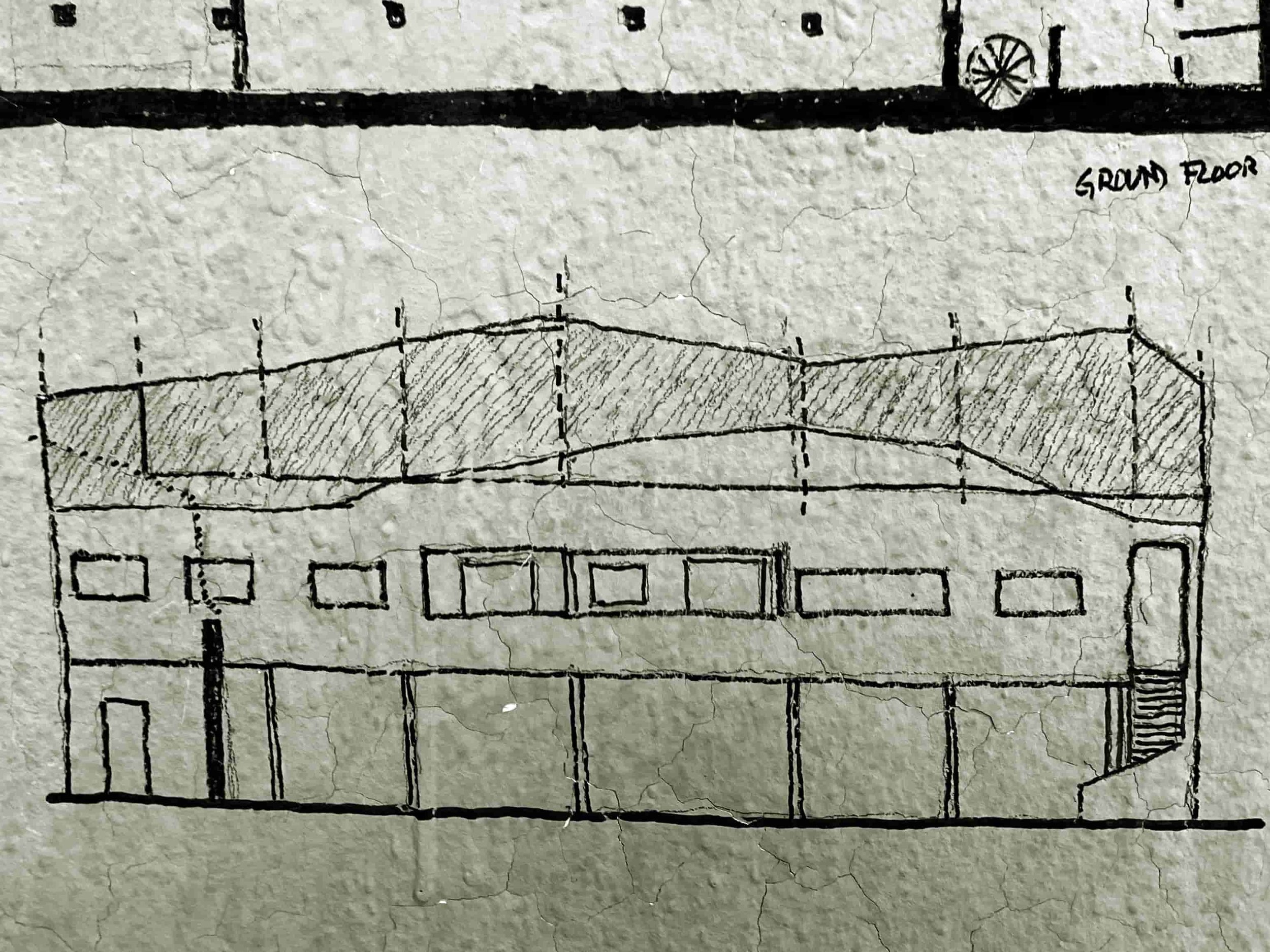

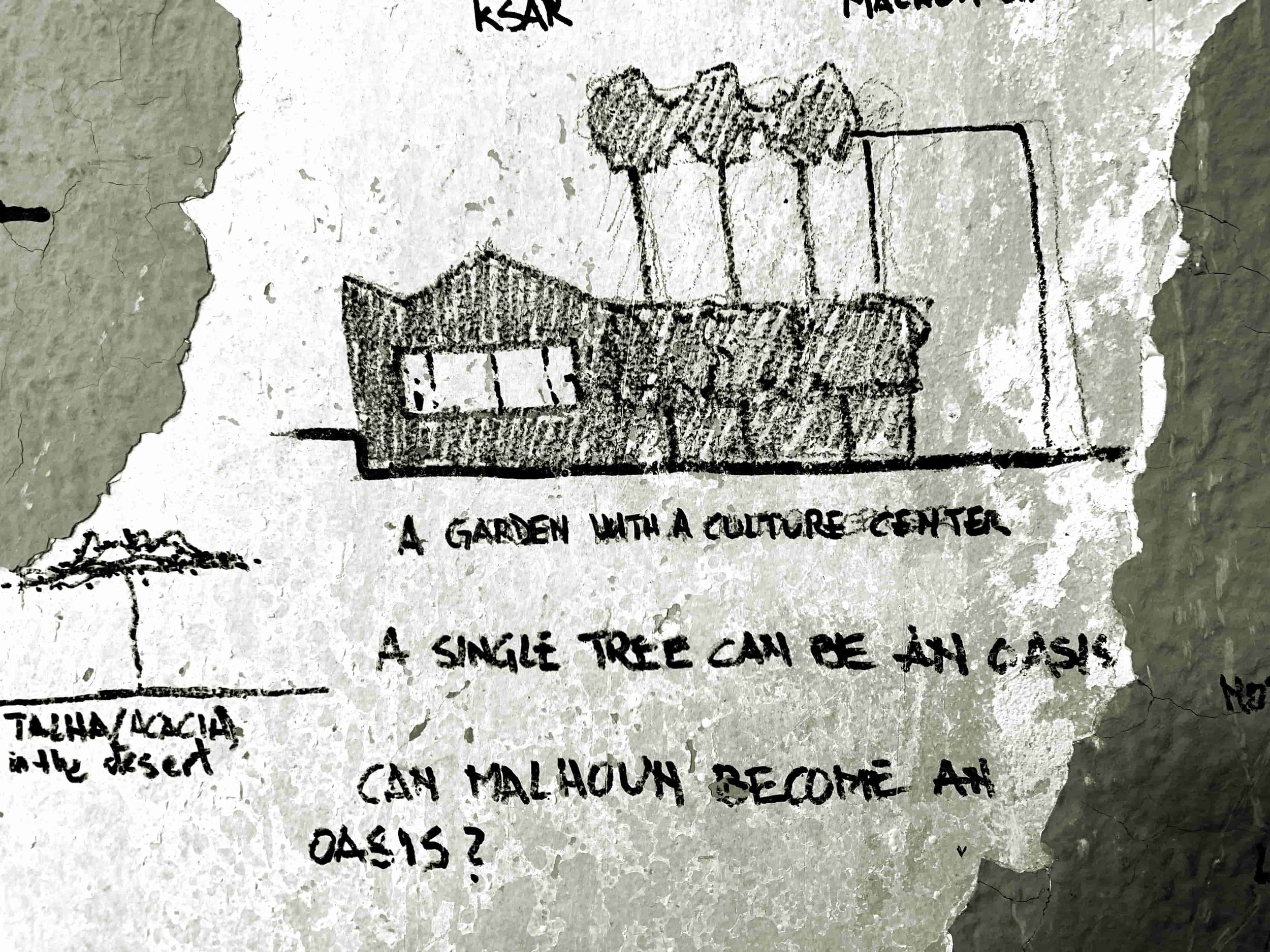

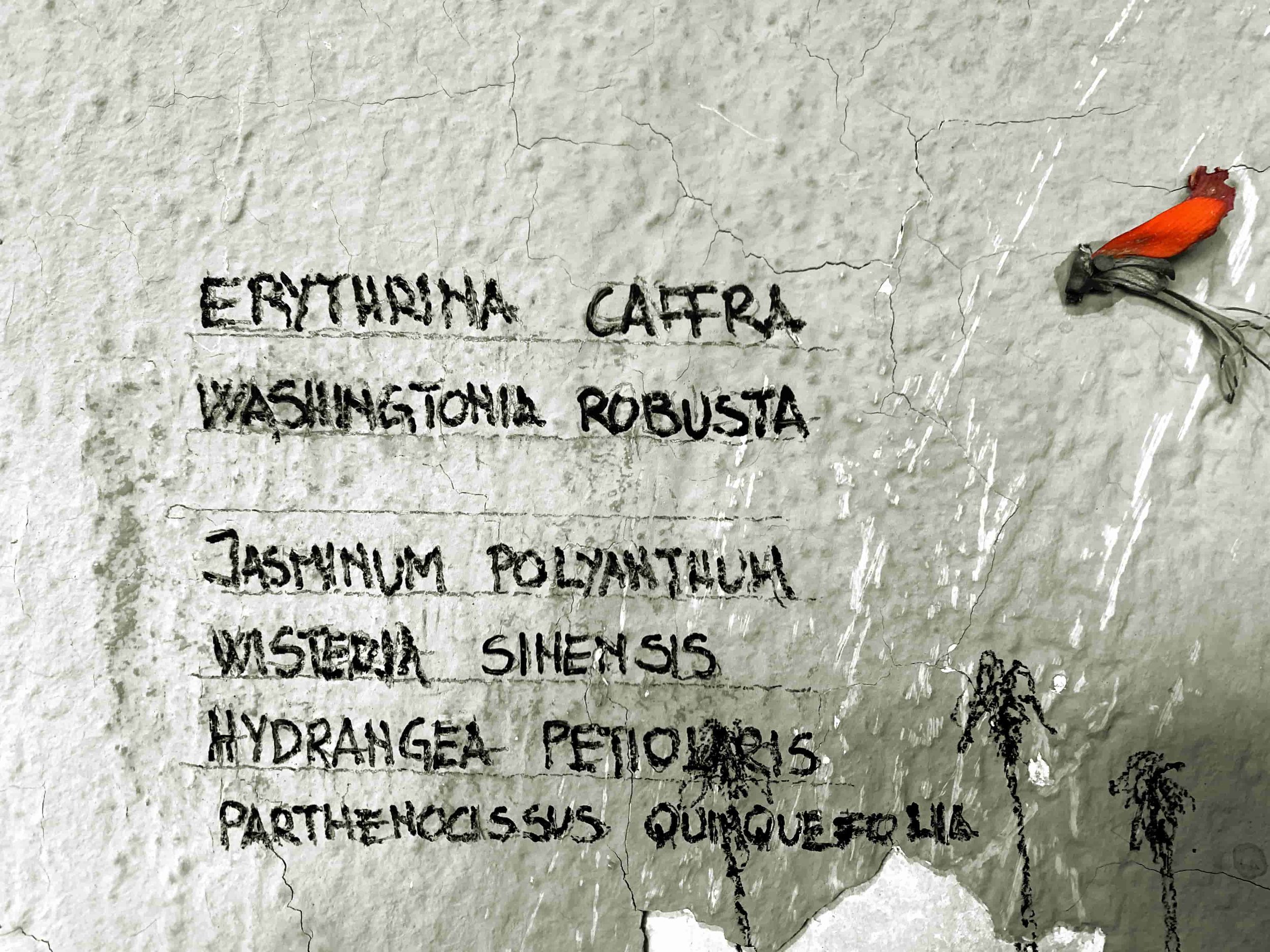

04.3 The architectural project drawn

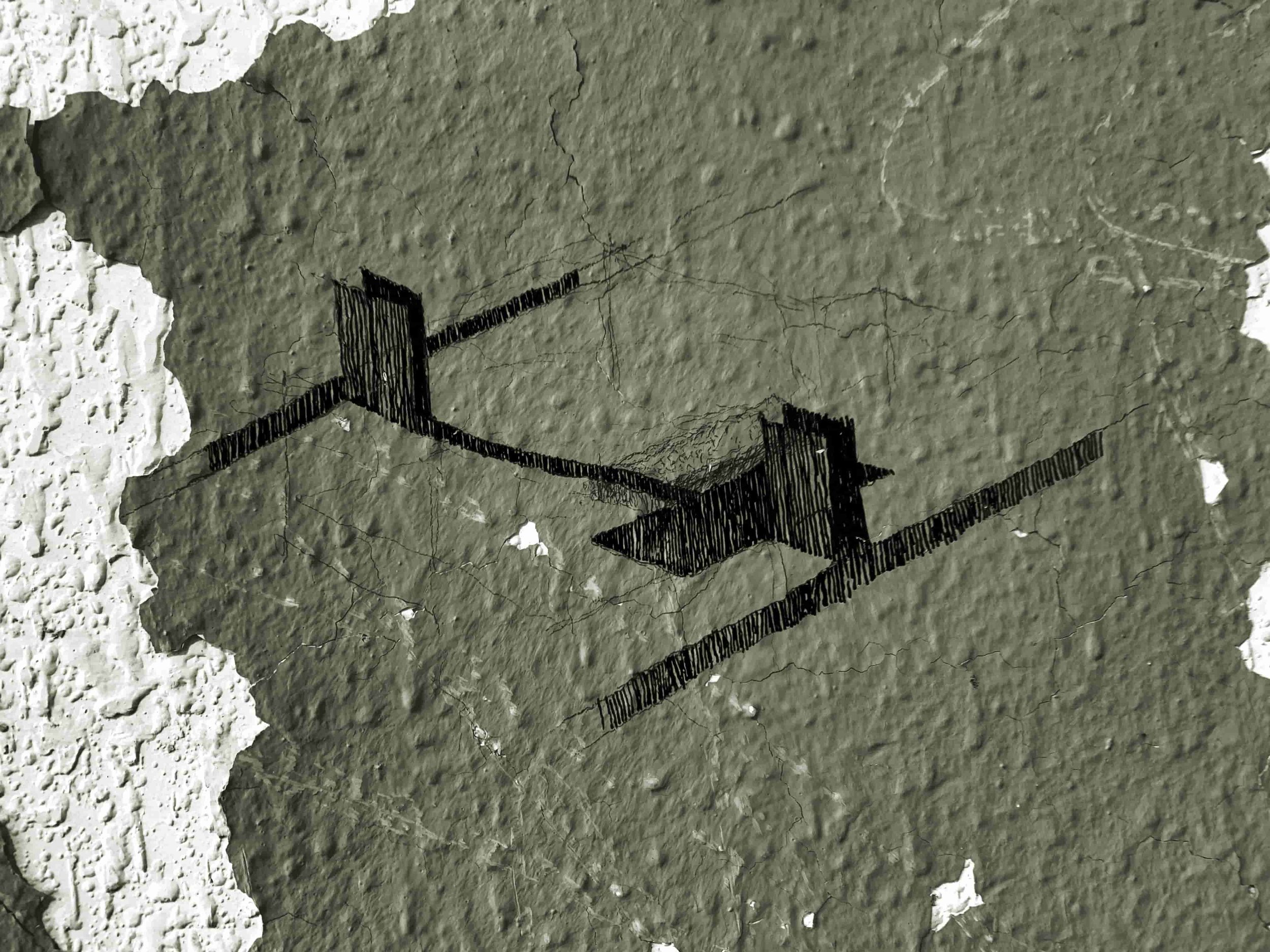

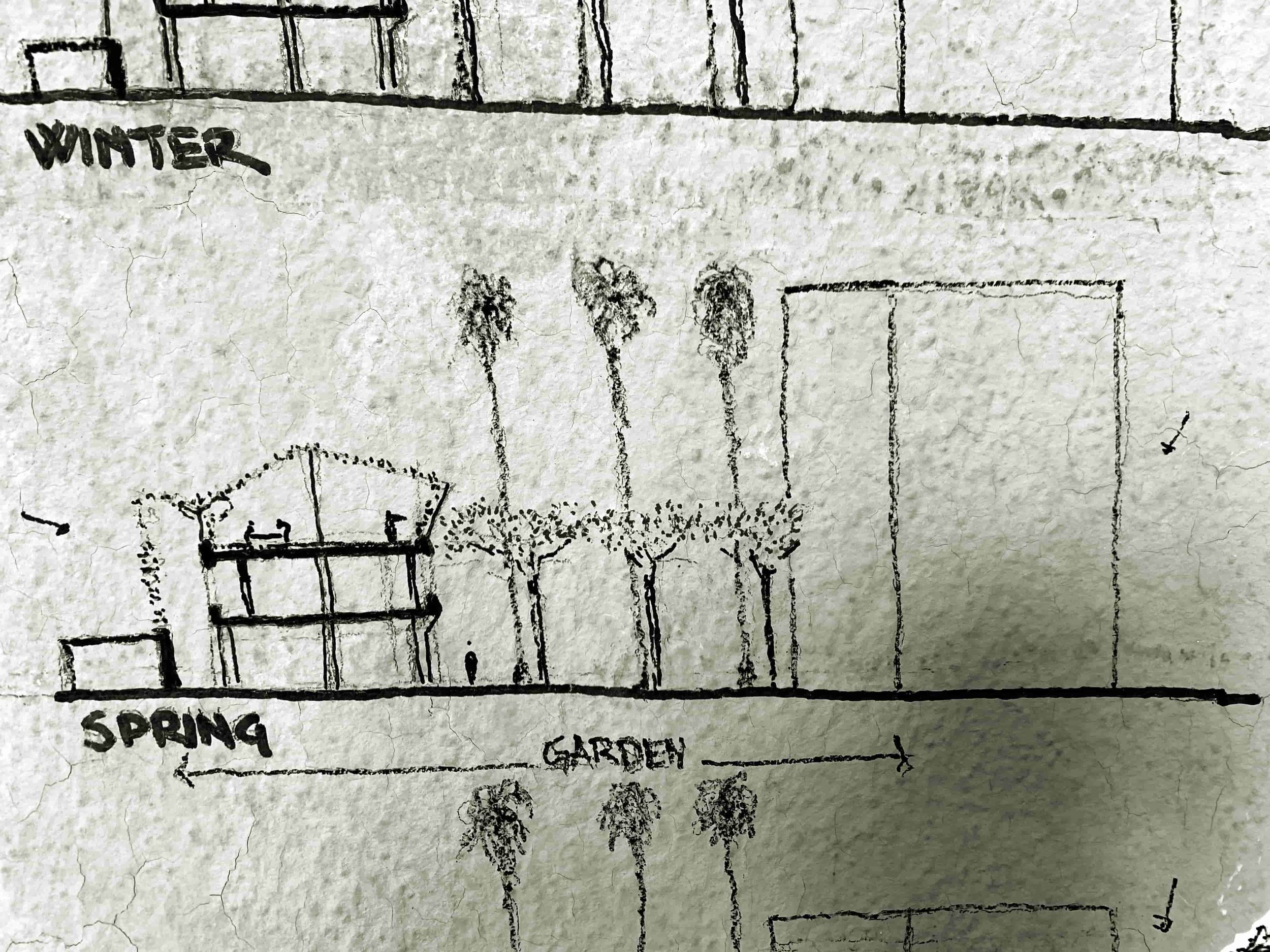

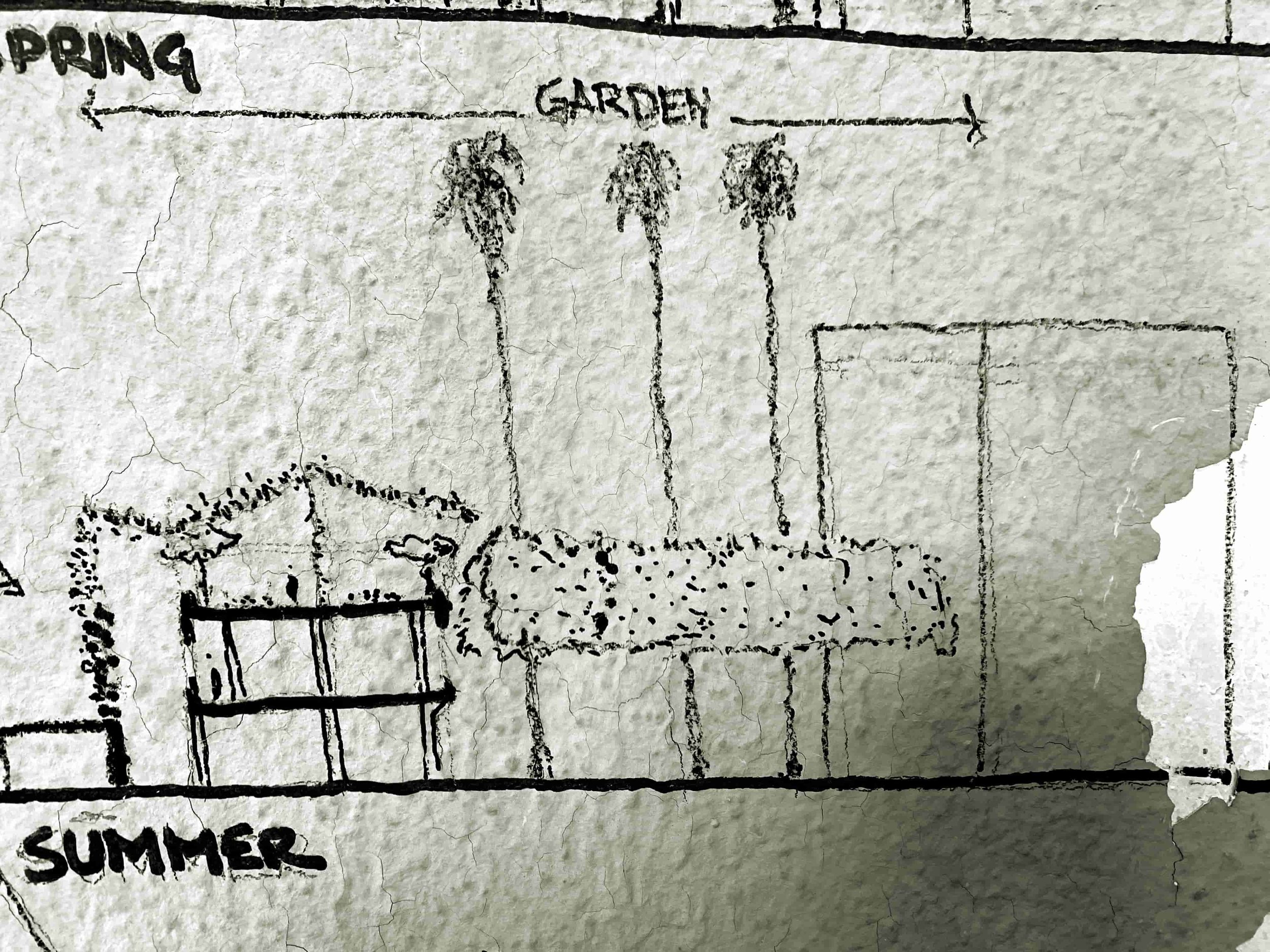

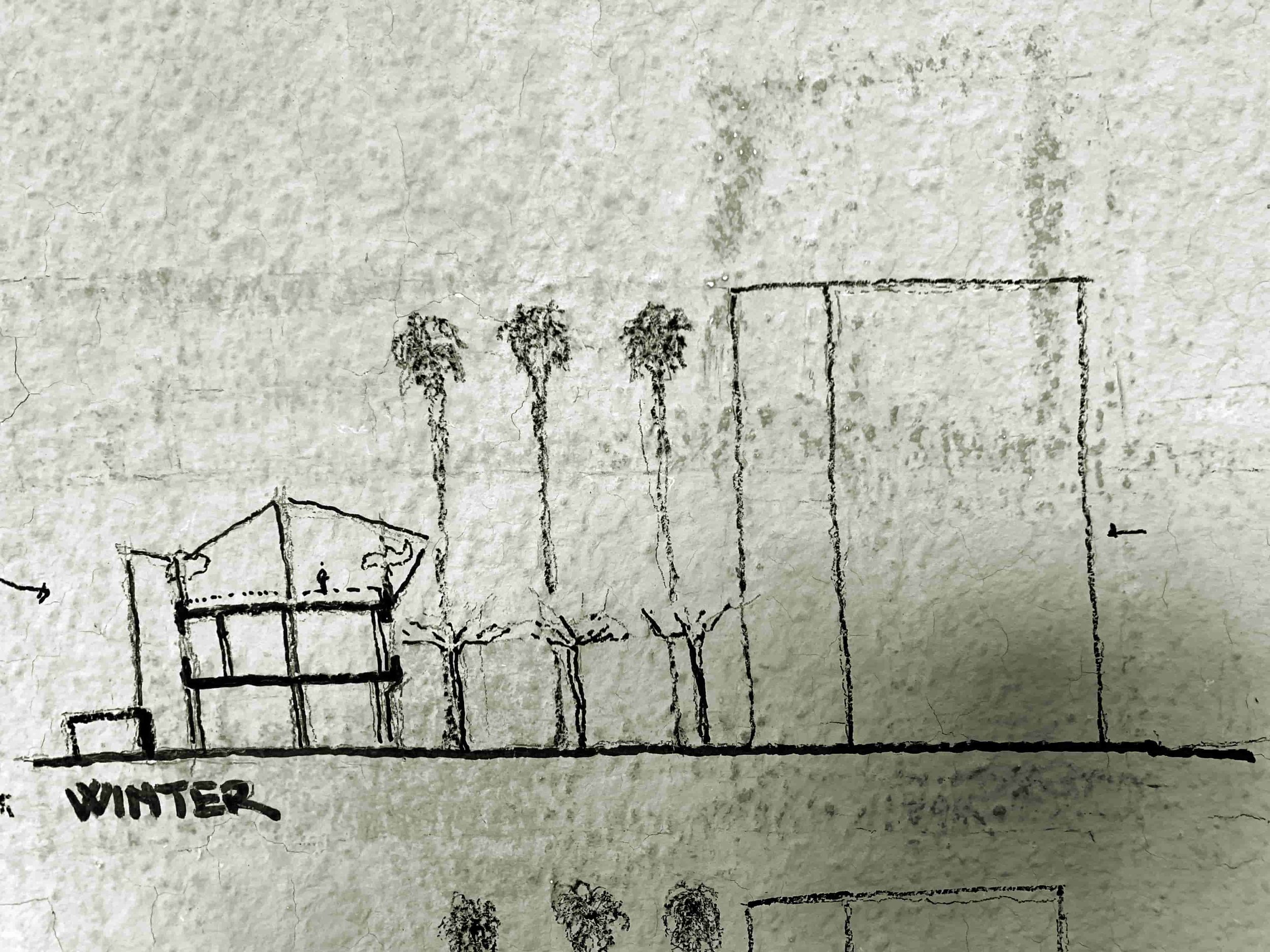

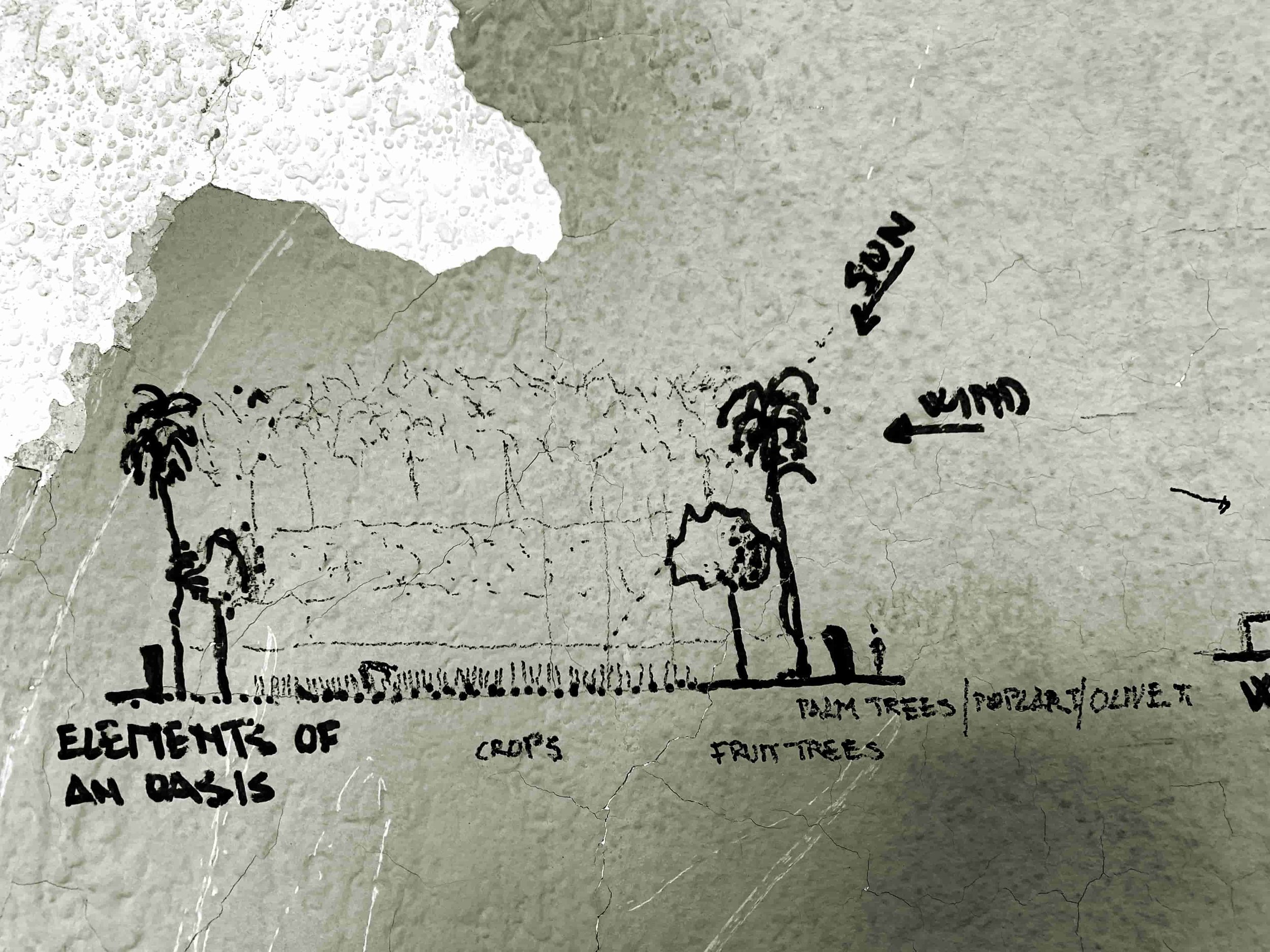

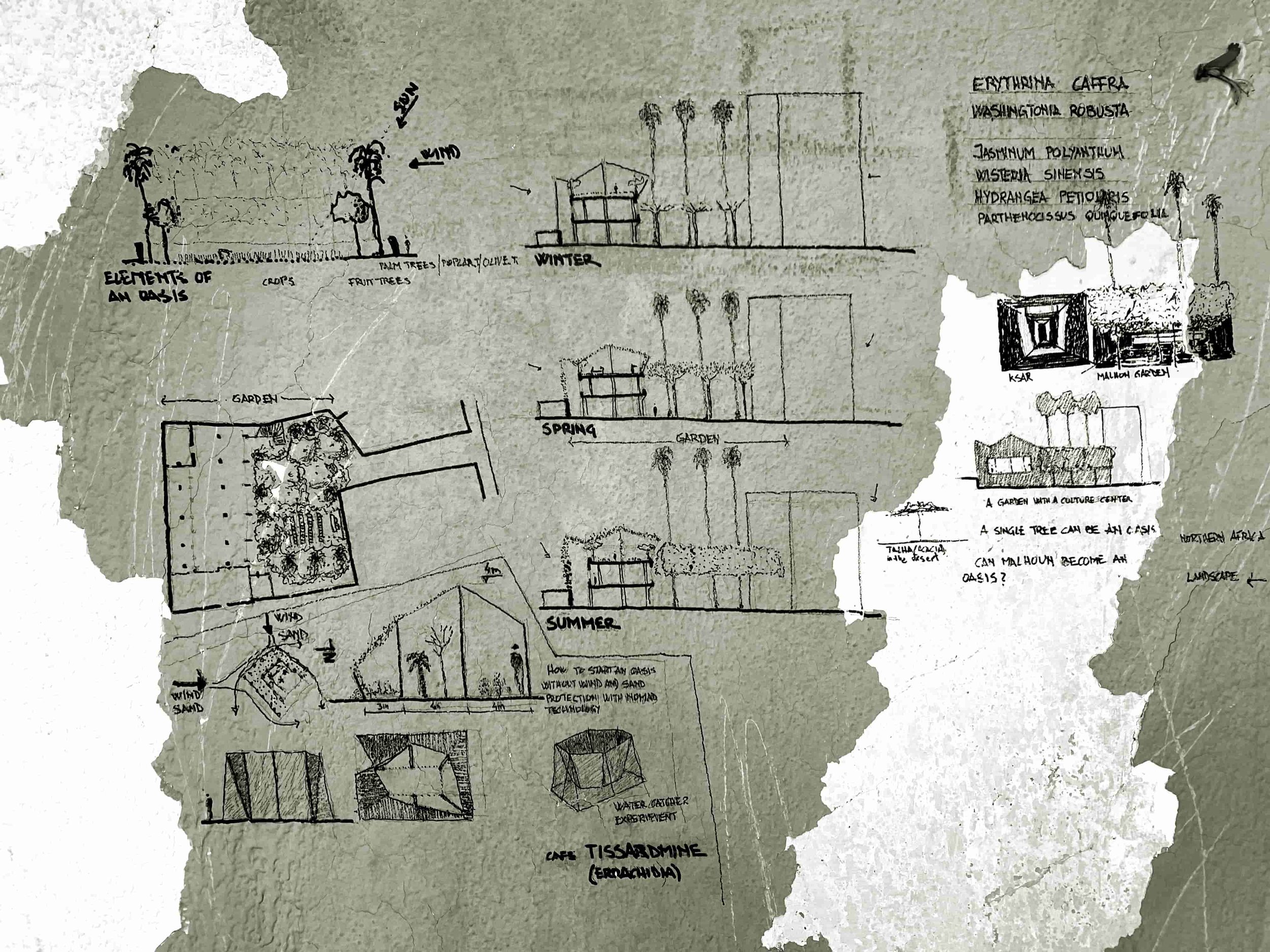

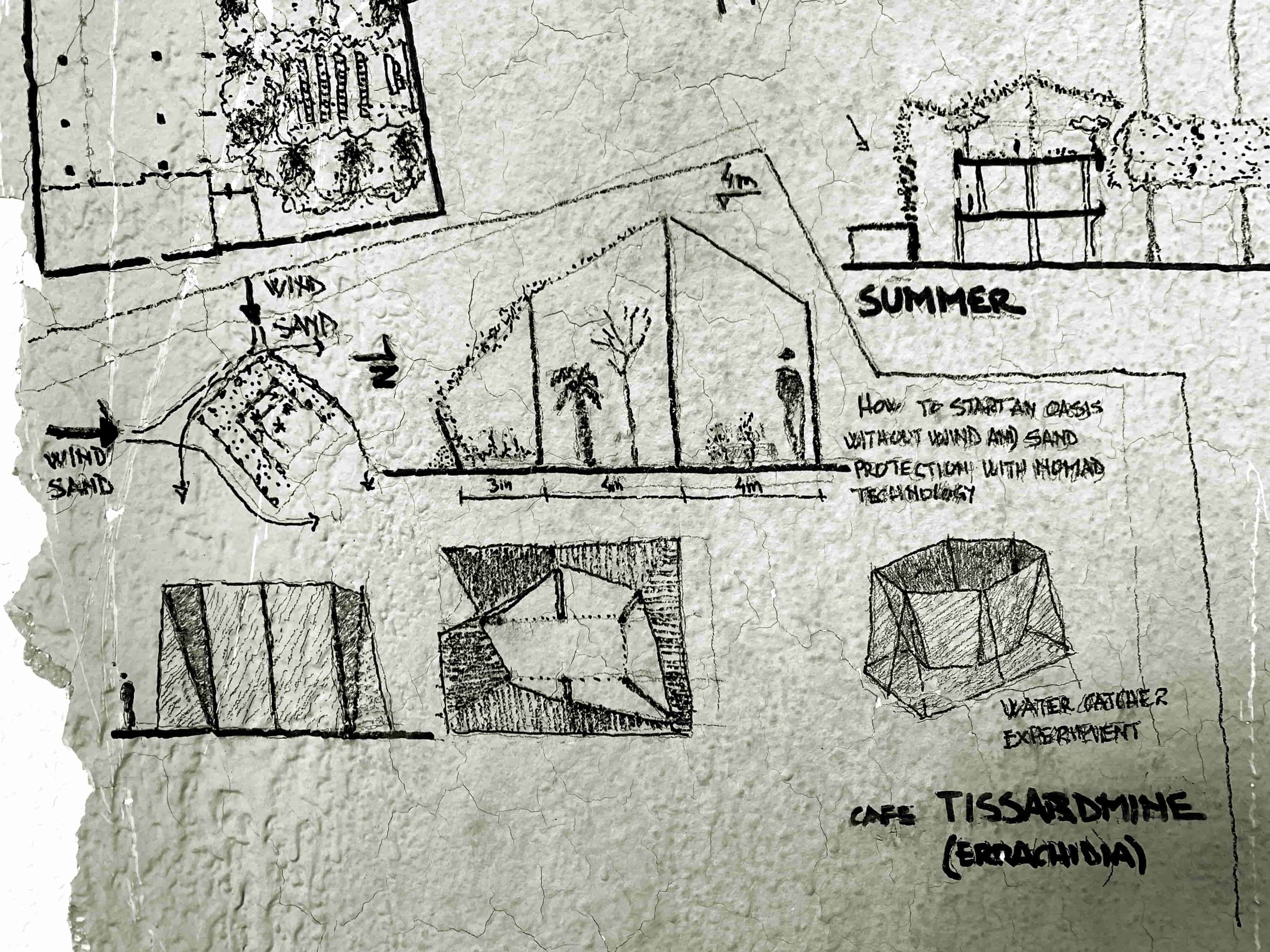

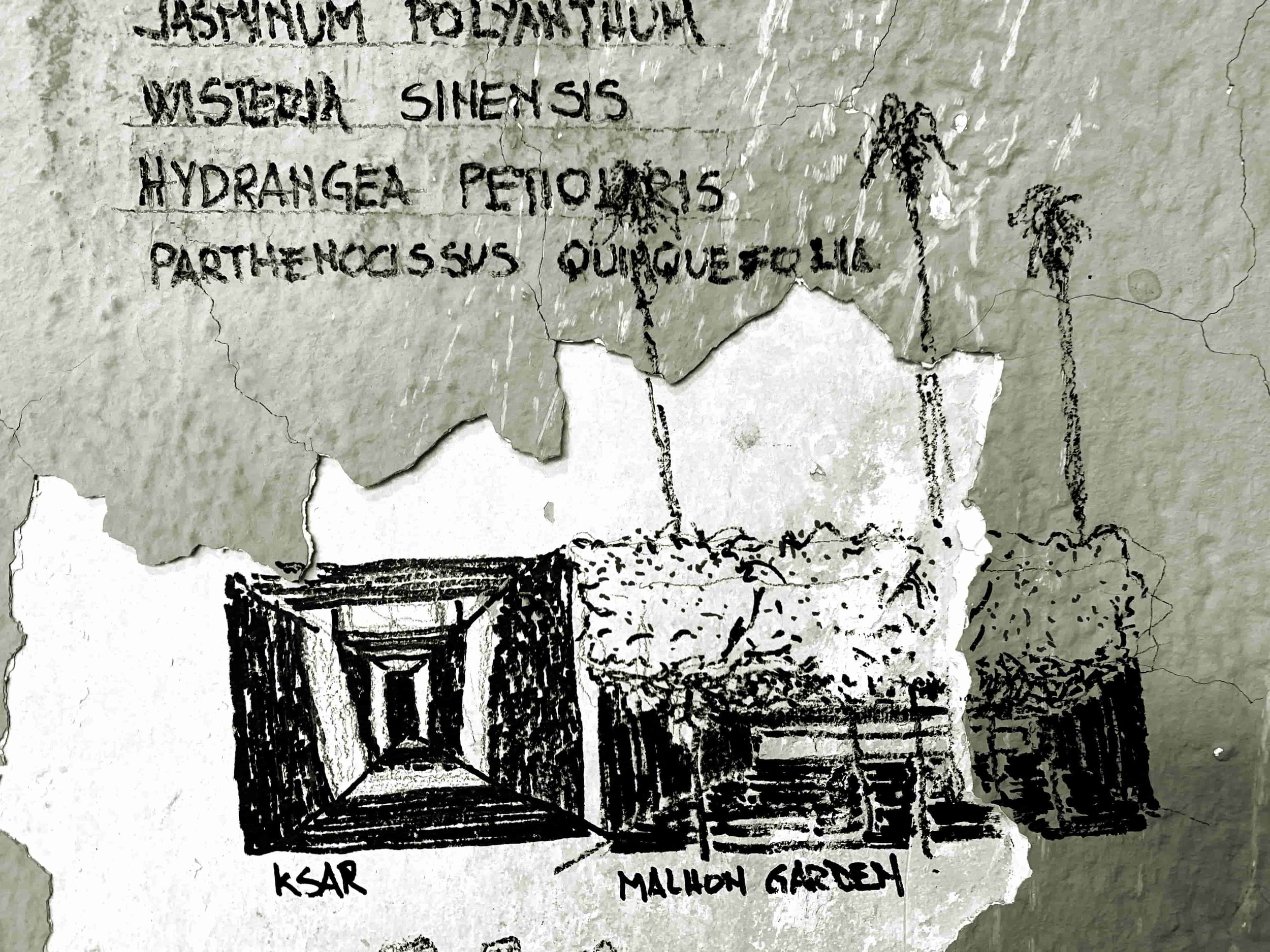

Although we had asked if it was necessary to prepare a text or a brochure with plans to explain the project, the curators did not consider this type of information necessary, but on February 4, once the place of the two models in the exhibition has been decided, one of the curators, Phillip, told us that it would be great to hang plans on one of the walls explaining the project. Five days before the opening, we still had to finish the copper model, monitor the construction site in the garden and make the plans that we had been asked for some art installations of certain artists. It was obvious that we didn't have time to think of posters that could explain everything about the project, and above all, because we had made models far enough away from the concept of architectural models to put them next to technical architectural plans. Our answer was negative, but following the spirit of the exhibition, where almost all the works adapted to the existing spaces and to their plastic and visual constraints, we proposed them to draw the project on two walls, explaining the main elements of the oases which have been considered and integrated, as well as the research carried out in the desert, the experience of which has served us to provide spatial, constructive and structural solutions. It was out of the question that the visitors could have thought that we had used the word OASIS in a very light way, simply because the project was in Marrakesh.

This solution gave us the opportunity to make small drawings between different moments and even continue them after the opening as ideas came to our minds or visitors asked us for more information.

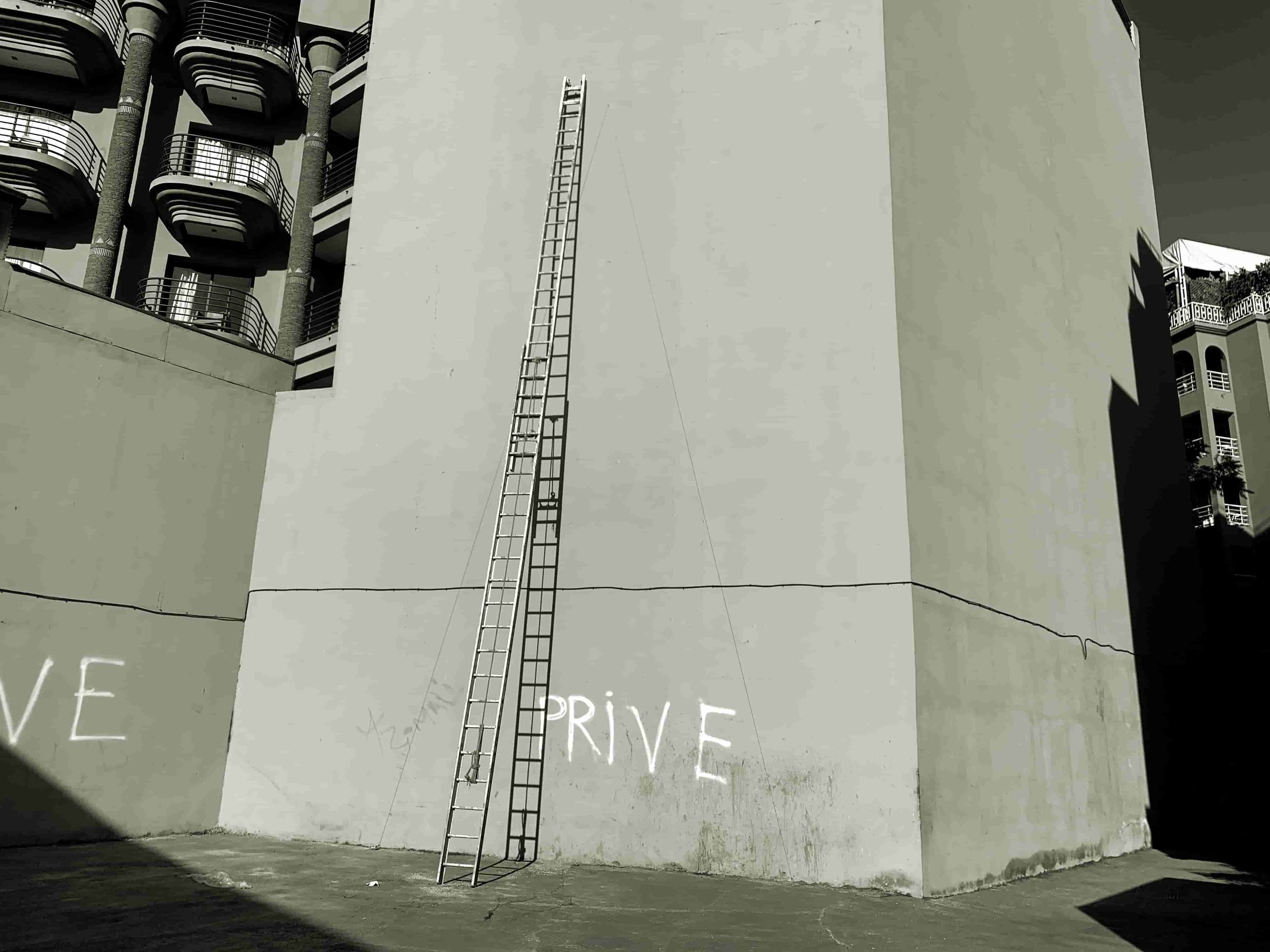

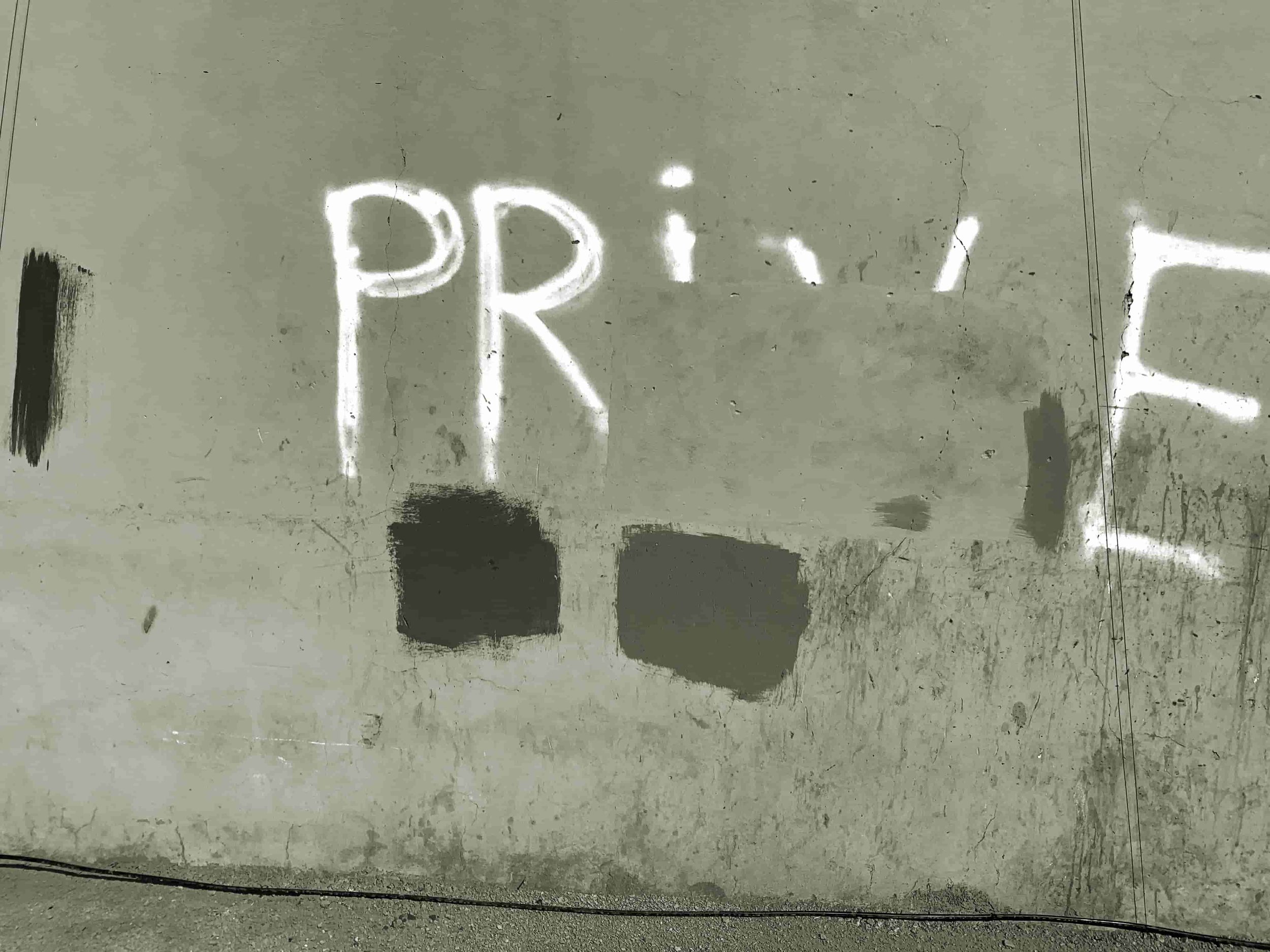

04.4 The parking works

In conversation with the promoters and curators, we had proposed them the conditioning of the parking because its current state was not ideal for welcoming the public who were going to visit the exhibition. They accepted but it was necessary to spend the minimum in budgetary terms. During these conversations, they asked us to change the image of the parking by using gravel painted in “Majorelle blue”. The Majorelle Garden is the most visited tourist spot in Marrakesh, created by the French painter Jacques Majorelle in 1931 who was inspired by the oases by painting many walls with a blue color, today called Majorelle blue. The garden had been bought by Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé in the 80s and now it belongs to one of the foundations they had created. However, this color should be called "Berber blue" since Majorelle had copied it from the ceilings of the workshop he used at the Taourirt kasbah in Ouarzazate, as the director of CERKAS, Mohammed Boussalh, had told me there years ago.

Kasbah Taourirt, Ouarzazate (Morocco)

Majorelle Garden, Marrakech (Morocco)

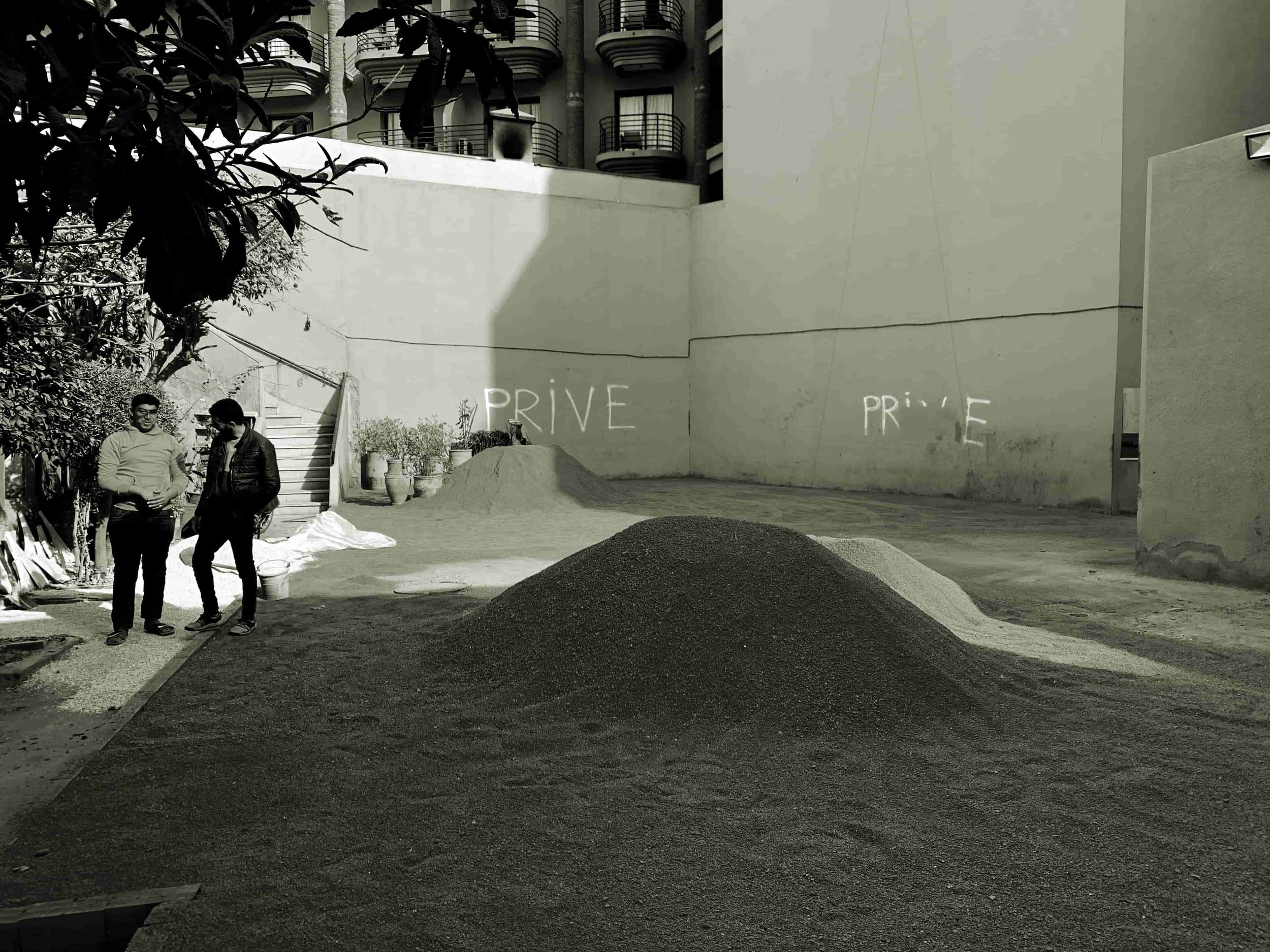

I was completely against the use of this color as a visual cue to notice that we were indeed in Marrakesh. By the way, I also had in mind the gravel, a material with which we could completely cover the floor of the car park and then, after the fair, return it to the quarry while waiting for the final works of the center. Also, it was clear that the gray gravel should be avoided, because it could give the impression of being on a construction site. We asked for samples from the quarries near Marrakech and we got pink and white gravels. We were leaning towards pink as the image was going to be closer to what we envisioned for the project when executed, with the garden finished with stabilized lime-reinforced soil, using (what I believed at that time) the same materials used on the alleys of the Cyber-Park of Marrakesh, and which had a red tint. While we were comparing the sizes and colors of the gravels, Eric did a test with red paint. Seeing the result, he was very sure to paint all the gravel in blue (or in another color), but for him it was important to radically change the image of the gravel and at the same time of the parking lot. Once again I was against it because he wanted to create an image, certainly very photogenic, but for me it was decoration and it was absolutely necessary to be coherent with the idea of the project, to find the spirit of the agricultural space, and we weren't going to achieve that by using blue synthetic paint.

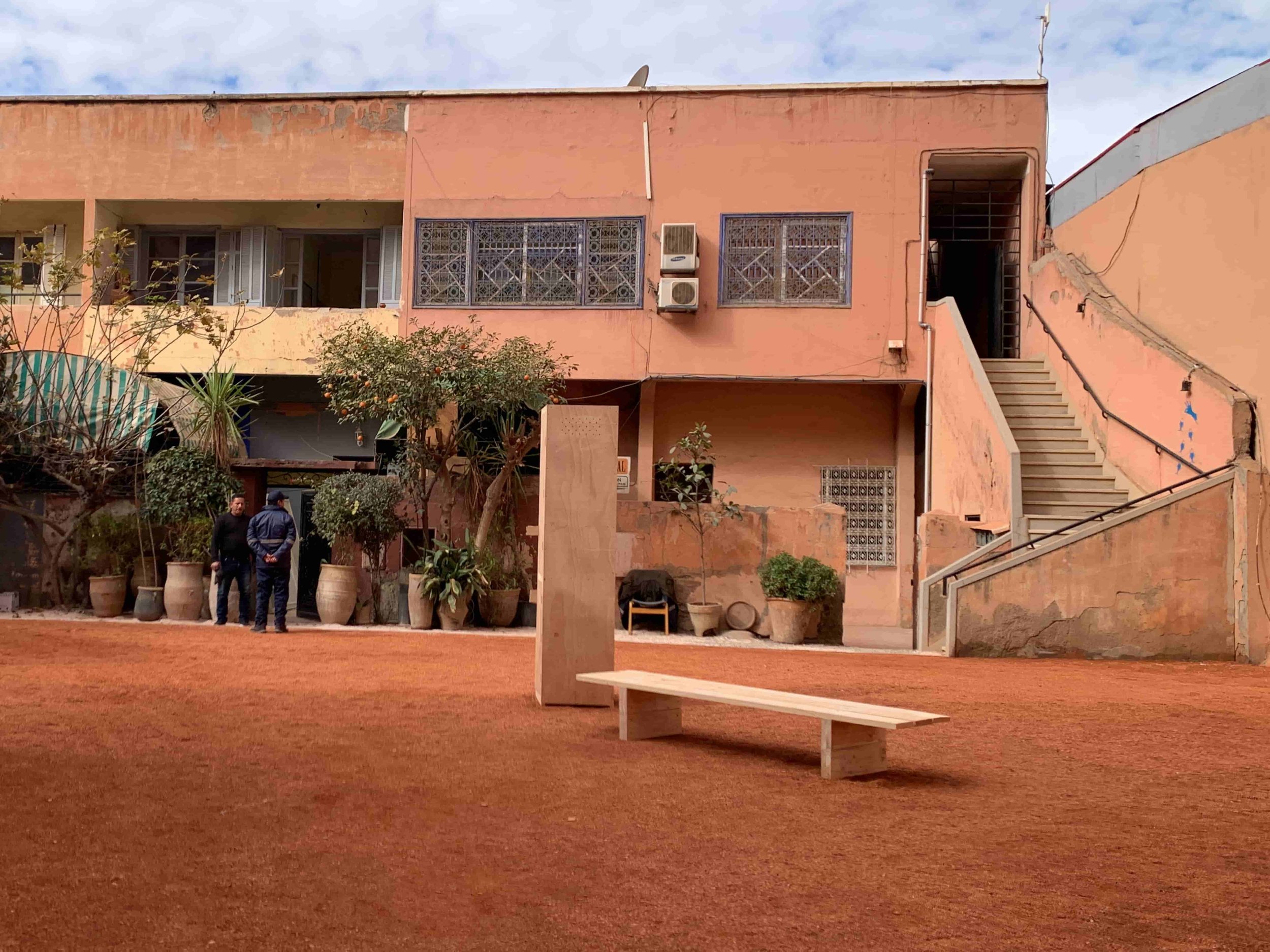

The contractor, Othmane, was following our conversations and at one point he explained to us why we weren't using crushed bricks, it was much cheaper and quicker to lay and it was the constructive solution used in the Arsat Moulay Abdeslam park. I did not know that park but the day before I had gone to take photos of the red alleys of the Cyber-Park, when I showed them to Othmane, he told me that it was the same park. For me there was no doubt that we had to use the same material for our project, especially after realizing that the works in the parking lot were not going to be temporary, but the first phase of the project, and therefore it would not be not a temporary solution but rather a permanent one.

There were still two elements that we considered essential in the renovation of the garden. For Driss, it was necessary to intervene in one of the party walls because of its strong spatial presence. He was right, but at the beginning it is true that the idea did not convince me, at least with those dimensions, because we risked giving the impression of wanting to make a very visible work of art, just like the promoters wanted with the use of colored gravels. The triangle proposed by Driss was going to be associated with one of the benches since the sun fell on this area on winter mornings, which would make it the most pleasant place in the future garden. As in the end brick dust mixed with glue was used to paint the triangle, the final effect was what Driss wanted in his sketches, giving continuity to the ground to modify the spatial perception of the whole and it worked very well.

If the real project was the creation of a garden as a legacy of what was once the city of Marrakesh, an oasis, it was necessary to begin the construction of this garden by planting, at least, one of the trees indicated on the plans. We had planned for Erythrina caffra, however, after calling and visiting several nurseries in Marrakesh and Ourika, we did not find specimens of a certain size, at least 4 meters. On the other hand we found in Marrakesh the Erythrina crista-galli, which normally reaches 15 meters in height, has a crown width of 6 to 8 m and has flowers, but of orange color (instead of the reds of the other variety), with an earlier flowering than the spring foliation, and which would create a rather spectacular orange image of the future garden. In addition, the specimen they had in the nursery was magnificent, with few flowers and a completely vertical trunk up to the branches. In the future, once all the trees planned in the project have been planted, it will be necessary to control their growth so that they do not exceed the roof of the building. On the other hand, a larger size of the trees will make it possible to have more free space between the ground of the garden and the crown of the trees and to distribute them more easily on the surface to host different types of activities.

On February 5, we started fitting out work, including temporary furniture, benches and a kind of furniture to install the video projection equipment. We made the benches with 40 mm thick pine wood planks because they were the ones that were used in the Fenduq to make the transport boxes for the works of art, in fact it was them who proposed this material because that way they could reuse the wood after the exhibition.

On the 8th the car park had become a garden.

Here is the evolution of the construction site during the 4 days that lasted the works and which had a budget of 64,440 Dh (6,196 €).

04.5 The promise of a trace

The curators of the first exhibition in the Malhoun Art Space were Phillip van den Bossche and Chahrazad Zahi and they invited artists that, most of them, had already produced works at Fenduq.

Poster: Nassim Azarzar

Even though our mission ended with the building permit application documents and the car park works, I would like to especially thank Eric and Samya for their trust and wish them a successful completion of the future Malhoun Art Space.

This project allowed us to learn more about the history of Marrakesh, we saw the importance the desert can have in understanding certain Moroccan cities, we enjoyed working with craftsmen and we were able to make many reflections on heritage, gardens, contemporary art, architecture, cultural development... In short, it was a real pleasure to work on this project.

Credits texts, photos and drawings: Carlos Pérez Marín