01. Preface

Cinema and literature give us an image of the desert that is, in most cases, idyllic and does not correspond to reality; spaces without limits, with sand dunes, with small oases, where there is nothing, where nobody lives, a hostile and dangerous environment… However, its geology is a clear sign that it is a much more complex physical environment, in which there is not only sand, but also stones, rocks, mountains, rivers… There is another aspect that could help us understand why the desert is a geostrategic space of utmost importance, despite this image of an inhospitable and abandoned habitat; the main dynasties that ruled North Africa and even the Iberian Peninsula came from the desert. Most of them are originally from the Sahara or settled there from Arabia before taking power; these are the Almoravids, the Almohads, the Merinids, the Saadians and the Alawites.

Near the oasis of La Gueila, Chinguetti (Mauritania)

Khneïg ed-Dalmé, Chinguetti (Mauritania)

The desert is important because by understanding it we will be able to better understand both historical events of the past and the material and immaterial heritage that they have left us and that we find not only in the geographical area of the Sahara, but also in the regions that were connected through the caravan routes, which means that Ceuta should be considered as a part of this legacy. Now, perhaps the most interesting thing is not what the inhabitants of the desert and bordering areas built but the mentalities that have given rise to this heritage, adapting to a place with an extreme climate and providing solutions to problems that these weather conditions cause in order to survive in this habitat. What is remarkable is that they do it using only the elements they have around them, mainly soil, although also stones, sand, wood (generally palm tree but there are regions where they use acacia or poplar wood), straw and some water. Materials with which to build not only houses but entire towns.

However, it would not be necessary to mention architecture exclusively, since what man has built in the river basins are agricultural spaces called oases, with a complex irrigation system and a social organization that have subsequently made possible the construction of architectures in which to live, such as the kasbahs, the ksars and the zawiya.

02. Introduction

However, adobe and rammed earth (or stone) constructions are not the only elements that we could define as cultural heritage, according to the classification made by UNESCO (according to the General Convention of UNESCO in Paris Oct-Nov 1972):

Article 1

For the purposes of this Convention, the following shall be considered as "cultural heritage"

>>> monuments: architectural works, works of monumental sculpture and painting, elements or structures of an archaeological nature, inscriptions, cave dwellings and combinations of features, which are of outstanding universal value from the point of view of history, art or science;

>>> groups of buildings: groups of separate or connected buildings which, because of their architecture, their homogeneity or their place in the landscape, are of outstanding universal value from the point of view of history, art or science;

>>> sites: works of man or the combined works of nature and of man, and areas including archaeological sites which are of outstanding universal value from the historical, aesthetic, ethnological or anthropological points of view.

If we were to apply this classification to constructions and works carried out in the desert, we would be limiting ourselves to regions that would not be in a desert but rather in what is known as pre-Saharan regions, which is still a minority percentage of the surface area occupied by the Sahara.

03. Geographical area

The Sahara (which means desert in Arabic) is the largest hot desert on our planet, dividing North Africa into two regions, the Maghreb in the north and the Sahel in the south, and occupying a strip that runs from the western coast to the eastern coast. A priori, it could be a geographical barrier difficult to cross, however, its inhabitants, and in ancient times the caravans (at least in the Atlantic part), had established a whole communications network (much denser than one might think) connecting the Maghreb with the Sahel, with the Middle East and with Europe. It is interesting to observe the behaviour of the nomads who still remain in these areas since their way of moving and relating is very similar to that of sailors (beyond the similarity between sea waves and sand dunes).

This maritime assimilation can give us clues to understand how the Sahel and the Maghreb are connected and how the transit is carried out. To begin with, logistics infrastructures are needed on both sides (such as ports) where travellers can gather before beginning their journey or where goods and passengers can be distributed once they have reached these points in order to continue their journey to other places. These areas are called pre-Saharan areas and are delimited in the north by the High Atlas mountains and the basins of the Noun, Drâa, Rheris and Ziz rivers in Morocco, and in the south by the Senegal River and the mountains and rocky areas of the Adrar in Mauritania.

Surface of the Sahara Desert with its northern and southern coasts of the Atlantic zone

04. Saharan regions heritage

If we stick to the built heritage in the Sahara, excluding that of the pre-Saharan regions mentioned, and without taking into account the heritage built by Spain during the colonial period (the cities of Smara, Laayoune and Dakhla), we would find practically no constructions of kasbahs, ksars or zawiya type, as these were nomadic territories. The only elements built by man would be the water wells, and as we move away from the "coasts", they become simpler until they become mere perforations in the ground, if at all, with stone reinforcement on their interior walls.

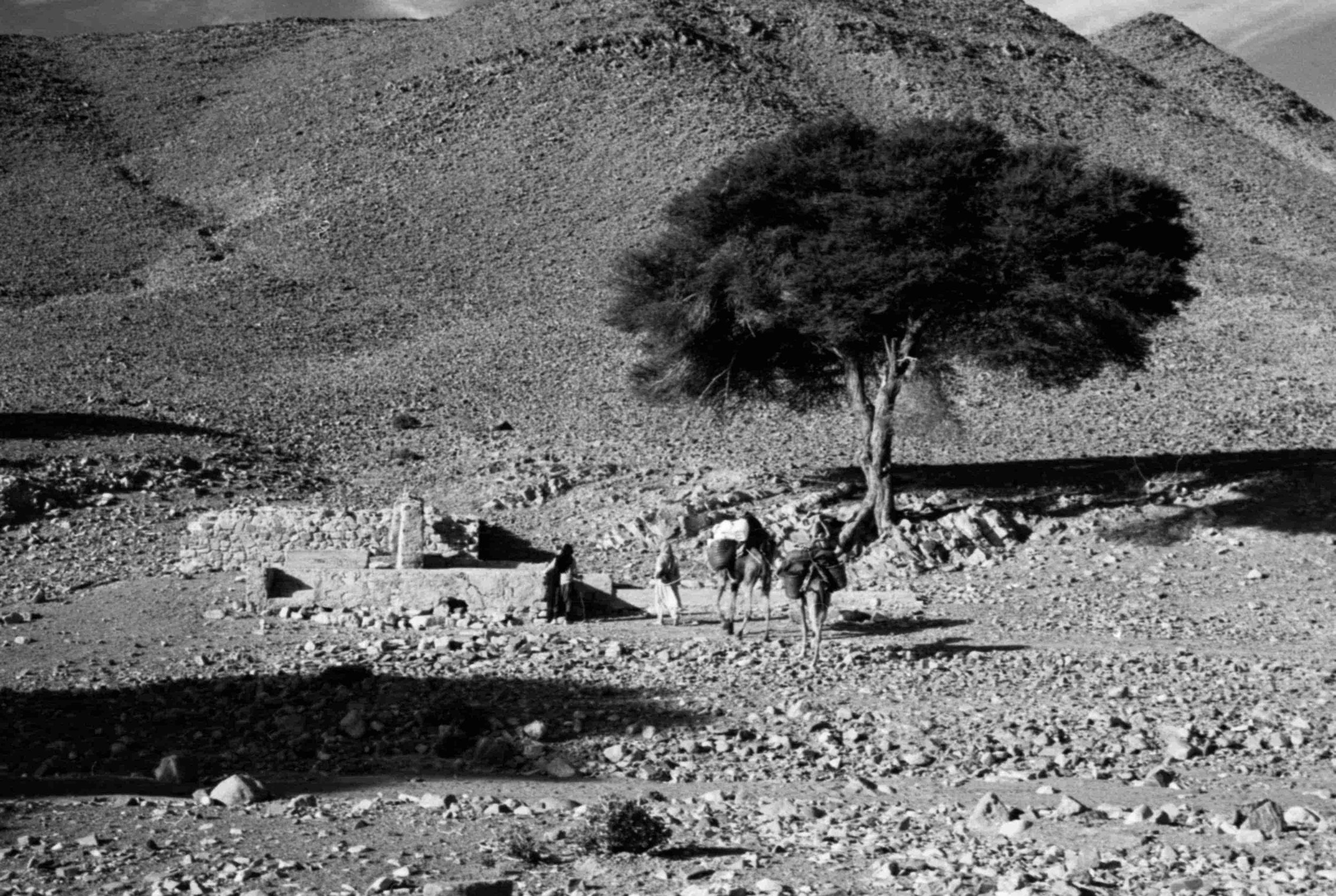

Water well near Tata (Morocco)

Water well near Oumjrane (Morocco)

Water well near Erg Chegaga, Zagora (Morocco)

Water well between the provinces of Adrar and Tagant (Mauritania)

05. Pre-Saharan regions heritage

In the “coastal” regions, the situation changed radically as a result of the caravan network, whose control implied supremacy in the commercial and economic sphere, but also in the political, military and cultural spheres. This importance was translated into the construction of logistics hubs capable of absorbing and supplying the flows generated. These logistics centres are nothing more than the oases (with a predominance of palm trees, acacias, olive trees and poplars) built in the valleys and basins of the rivers Noun (in Guelmim), Drâa (Zagora), Rheris and Ziz (Errachidia) in the Moroccan part, and the oases created on the edges of the Adrar plateau in Mauritania.

Inside or on the edges of oases, ksars (fortified villages), kasbahs (fortified houses) and zawiya (religious centres created by Sufi brotherhoods) were built, with variable dimensions and which could complement each other depending on the social organisation of the oasis, but generally no more than two tribes occupied (and occupy) some of these habitable spaces. Adobe and rammed earth were usually used, although there were regions and locations where stone could be the main construction material, as in the Adrar region of Mauritania or in the fortifications built by the Almoravids in the 11th century at strategic crossroads of the caravan routes from Mauritania to the Mediterranean coast.

In addition to their architectural importance, the zawiya could represent religious, social and cultural power. In fact, the sultans had to ensure both military and religious support, which was only offered by the acquiescence of the zawiya and their leaders, to the point that sometimes the power of a dynasty emanated directly from the zawiya. This was the case in the 16th and 17th centuries with the Saadi dynasty, which emerged from the Naciria zawiya, now physically located in the Tamgrut ksar, south of Zagora, but whose initial location is still unknown (although it was in the same palm grove of Fezuata). We are dealing with an intangible heritage of great value since this dynasty made use of culture and education as an instrument of power and although the existing library has no architectural or historical value, the books preserved in it are witnesses of this cultural power exercised from Marrakech to Timbuktu (the oldest book comes from Córdoba and is dated to the 11th century).

Zawiya of Tamgrut, Zagora (Morocco)

As integral parts of the kasbahs, ksour and zawiyas, we have elements of great uniqueness and heritage interest, despite the total lack of knowledge of their dating due to the absence of research work adapted to the construction systems of the oasis. In the Drâa valley in Zagora we find a succession of six palm groves along the Drâa river with a length of 200 km, which house 233 ksars, 26 kasbahs and 40 zawiyas. In all of them there was a mosque but in the most important ksars there could be two or even three. In total, there were about 400 mosques, of which only 5 had minarets, nowadays only 3 remain (Tinmasla, Amezru and Nasrate), showing us the height that adobe and rammed earth constructions can reach and that these architectural elements are dispensable.

Minaret of the Amezrou mosque, Zagora (Morocco)

Minaret of the Tinmasla mosque, Zagora (Morocco)

Minaret of the Nasrat Mosque, Zagora (Morocco)

The mosques of Adrar in Mauritania are not inferior, built in stone and stripped of even more construction elements to the point that the ground can even be sand from the nearby dunes, as is the case in Chinguetti.

Ouadane (Mauritania)

Chinguetti (Mauritania)

Chinguetti (Mauritania)

Generally associated with the zawiyas (they can also be associated with the ksars) and built as isolated buildings, we have the marabouts. Originally, they are where a Sufi saint was buried, but a simple burial could later give rise to an entire zawiya and therefore to a town or village (in cities like Marrakech they become districts of the medina), becoming places of passage for caravans for the simple fact that they could provide baraka (luck and divine protection) to travellers.

Marabout of Tazrut, Zagora (Morocco)

Other heritage buildings are the synagogues. It is believed that the first Jewish tribes arrived with the Phoenicians along the Atlantic coast. However, their establishment has only been proven from the 2nd century BC onwards and they managed to establish independent kingdoms, as evidenced by the heritage that has come down to us in the pre-Saharan regions north of the Sahara, such as entire neighbourhoods, mellahs, and, within them, religious buildings such as synagogues. It is worth noting the fundamental role played by some sedentary Hebrew tribes, as they controlled the economy derived from the caravan trade and some even created oases and ksars on both sides of the Sahara. This is indicated by oral tradition regarding the existence of a tribe, the Bafurs, originally from Mauritania but who also had a presence in Noul Lamta (today in the province of Guelmim, Morocco).

Ifran Anti Atlas synagogue, Guelmim (Morocco)

Perhaps the most important building of all those built in these regions was, and is, the granary or agadir, still used in some villages; authentic fortifications in which to store cereals, ensuring the survival of the population for at least 5 years in the event of prolonged droughts or sieges. These fortifications are usually at the highest levels of the village and could be built of adobe and rammed earth or stone, always adapting to the topography, regardless of its shape, giving rise to singular volumes and surfaces, as is the case with the granary of Amtudi in Guelmim. In addition to its shapes, it stands out for the 9 levels it houses inside and which, given its proportions, would resemble those of a small skyscraper.

Aguelay granary in Amtudi, Guelmim (Morocco)

Sometimes the granaries could also temporarily house the inhabitants in case of attacks, practically becoming small ksars.

Id Aissa granary in Amtudi, Guelmim (Morocco)

However, the majority of granary typologies are represented by buildings similar to kasbahs, with a quadrangular construction and towers at the corners, made of adobe and mud brick.

N’Ougdal granary, Ouarzazate (Morocco)

Apart from the architectural constructions, it must be remembered that the oases would not exist without the presence of water, and more importantly, without the correct management of this resource. The main contribution of water is that which arrives through the rivers that run through the valleys, but with very variable flows depending on the seasons of the year, giving rise to periods of drought, which served to regenerate certain flora and fauna when the population (and their animals) moved to more humid places, but there could also be large floods and therefore inundations, with sometimes devastating consequences but which allowed a “washing” of the land and in particular of its salinity. In order to exercise control over these circumstances, the Almoravids carried out a series of hydraulic works during the 11th and 12th centuries in the surroundings of Sijilmasa (Rissani), which are still active today although renovated; small dams, containment, direction and distribution dams, canals, waterfalls...

Check dam, Rissani, Errachidia (Morocco)

To a lesser extent, the water supplying an oasis may come from underground springs, which also require their corresponding hydraulic works, as is the case in Tighmert, Guelmim (Morocco).

Check dam, Tighmert, Guelmim (Morocco)

When the flow of rivers and springs is not sufficient, people resort to elements that date back to the Persian Empire: the khettaras or qanats. These are underground conduits to carry water from springs or groundwater found next to hills and mountains to the oases, distances that can reach dozens of kilometres and that require ventilation wells and constant maintenance to ensure the hygienic conditions of the water and the flow of the same in case of a decrease in the levels of the main supply source, which implies new excavations to adapt to the new levels, allowing the arrival of water by gravity through these underground channels. In the province of Tinghir (Morocco) there are khettaras with up to 15 m depth.

khettaras of the Jorf oasis, Errachidia (Morocco)

khettaras of the Jorf oasis, Errachidia (Morocco)

The last element of the irrigation system, already in the oasis itself, is the distribution system by means of canals, which are blocked or plugged to divert the course of the water to one area or another of the oasis so that all the plots can have the corresponding water time according to the pre-established calendar and which normally has 33 days in winter and 34 in summer (with one day reserved so that the nomads temporarily established in the surroundings can collect water). This system works 24 hours a day and is an element of social cohesion since it forces them to be in constant communication by varying the day and time of irrigation each month, although with the creation of new private wells on an almost massive scale, this social organization around water is disappearing at great speed in the pre-Saharan regions. The fact that the water reaches all the plots by gravity determines the route of the canals and, as a consequence, the network of small roads and paths that give access to all the plots. It could be said that public spaces are determined by water.

Channel distribution in Erfoud, Errachidia (Morocco)

Map of the Tighmert canals, Guelmim (Morocco), drawn by Ahmed Dabah, Ahmed Sabar, Hamza Sabar and Taufiq Dabah

For the inhabitants of the oasis, the main water supply is provided by the wells, and if there is only one in the entire ksar, it will always be in the mosque, in the space reserved for minor and major ablutions (the latter requiring specific spaces to wash the entire body). The presence of underground water therefore determines the position of the well and the mosque, with water once again being the element that organises the space.

Tizguine, Zagora (Morocco)

If it happens (due to topography and geology) that the water well cannot be located in the habitable core, then the well will have to be fortified to allow its use during possible attacks and sieges. This situation arises in the Mauritanian city of Ouadane where the well extends into the oasis while the city was built on a rocky hill without water.

Fortified well in Ouadane (Mauritania)

Once the main elements of the architectural heritage of the pre-Saharan regions have been explained; kasbahs, ksars, zawiyas, mosques, marabouts, synagogues, hydraulic works... it is pertinent to explain how the oases are related and connected. At a local level, the organisation of the territory will be determined by geology, topography and water resources, and it is also essential to have dimensions that allow the existence of oases in such a number that they can become a logistical hub, as we saw at the beginning. These conditions have given rise to three types of organisation in the main logistical hubs of the caravan routes that connected Morocco and Mauritania.

The Adrar region in Mauritania is a sandstone plateau with cliffs and mountains that give rise to some seasonal rivers and small valleys. It is on the edges of this plateau that the main oases are located and therefore the sedentary population; Ouadane, Chinguetti, Atar, Azugi, Terjijt… Around this plateau the characteristic type of terrain is that of sand dunes with few water wells.

Adrar region (Mauritania)

The first set of oases that the caravans encountered when heading north was the one built in the basin of the Noun River at Guelmim, already on the northern bank. This region was known as Noul Lamta and its “capital” was located at the oasis of Tighmert. In this case, it is the mountains and the water courses (again seasonal) that determine the space and the arrangement of the oases on the edges of the basin.

Noun River basin, Guelmim (Morocco)

Finally, we have the valleys. In Zagora, the valley of the Drâa River as it passes through Zagora has allowed the creation of six palm groves (Mezguita, Tinzuline, Ternata, Fezuata, Ktaua and M’hamid) along 200 kilometres, where more than 200,000 people currently live, although most of them live in the urban centres created during the French protectorate and with a considerable increase in both area and population in the last decade, with the consequent abandonment of the ksars. In the following image, the black dots represent the 299 kasbahs, ksars and zawiyas that for centuries housed the different Draoui, Berber, Arab and Hebrew tribes that inhabited the valley.

Drâa River valley, Zagora (Morocco)

A similar situation is found in the province of Errachidia, where the Ziz and Rheris rivers give rise to a series of oases with a length of 150 km.

These three basins became the departure and arrival points for caravans heading to, or coming from, Mauritania and Mali. In short, they were the Saharan ports on the northern coast of the Sahara, although at a certain point in history there was a fourth port, Tamdult, near the oasis of Akka in the province of Tata, but it was not as important for as long as the others.

Main Saharan ports of Morocco; Noul Lamta (Tighmert); Tamdult; Taragalte (M'hamid el-Ghizlan); Sijilmasa (Rissani)

Once we know the architectural heritage of the desert, the relationship between the different elements and the connections between the oases, it will be easier to understand the heritage of cities that, although apparently have nothing to do with the Sahara, being north of the natural border, the High Atlas Mountains, are in fact an example of how the knowledge and experience of living in this habitat has allowed cities to be created from scratch, until they became the capital of empires that settled in the Iberian Peninsula, in the Maghreb and in the Sahel.

Marrakech was founded around 1070 by a confederation of nomadic tribes whose area of movement was between the High Atlas Mountains in Morocco and the Senegal River in Senegal. The Lamta, Gudala (or Jazoula) and Zanhaga (or Zenega) tribes decided to join together and begin an expansion whose scope required the founding of a city located in a more central location with respect to the surface area they had to control. Initially, the tribal chiefs considered settling in the city of Aghmat (30 km southeast of Marrakech), the capital of the region, but due to the impossibility of increasing its extension, given the presence of the first foothills of the High Atlas, in the end they decided on a place where there was only a river, several tributaries and wastelands with the presence of bushes and few animals according to the chronicle of Ibn Idhari of 1312 (al-Bayān al-mughrib, translation by Ambrosio Huici Miranda 1963); we have chosen a desert place, where there were no living beings other than gazelles and ostriches, and where nothing grew but lotuses and coloquintos. There they created, not a city (which would correspond to the current medina), but an oasis, an agricultural space where the most important thing was to bring water from the mountains given the irregular flow of the rivers. To this end, they had to build a multitude of khettaras, as well as pools to store water and later use it both for irrigating the plots and for distributing drinking water within the medina. Some of these pools still exist and provide services to the fields surrounding the ancient city.

Khettaras of Haouz in Marrakech (Morocco) according to Cornel Braun (1975)

Hypothesis about the original oasis of Marrakech (Morocco) between the 11th and 12th centuries

Agdal gardens pool, 12th century, Marrakech (Morocco)

In the medina, the main heritage buildings are the fortifications, with 18 km of walls and 11 access gates, as well as the kasbahs that have been used as royal palaces, as was the case with the Badi palace or the current Dar al-Majzén. The mosques are also notable (Kutubiyya, Ben Yussef, Mulay el-Yazid, Mouassin, Bab Doukala…), but in addition to the religious building itself, they are even more notable for the socio-educational-cultural complexes that were associated with them; a Koranic school or madrasa, a library, housing, public fountains, baths… Some of these complexes had their origin in a marabout and the importance of the complex was directly related to the relevance and power of the saint buried there and his followers. This is what happens with the zaouia of Sidi Bel Abbas as-Sabti, born in Ceuta and one of the seven saints of Marrakech. The Saadi dynasty built an imposing complex that continues to be a place of pilgrimage for the poor. In reality, we are faced with models that have been developed and expanded with respect to those existing in the desert ksars, used by dynasties to exercise greater soft power over their own and surrounding territories, through religion, culture and education.

Zawiya Sidi Bel Abbas, Marrakech (Morocco)

Zawiya Sidi Bel Abbas, Marrakech (Morocco)

Zawiya Sidi Bel Abbas, Marrakech (Morocco)

However, the entire “urban” development of Marrakech and its influence would not have been possible without the caravan trade that made the city a true cosmopolitan centre, directly connected to the Sahel, the Middle East and Europe. Precisely, in order to control this trade it was essential to guarantee the security of the different routes. To do this, the Almoravid dynasty built a series of fortifications from Mauritania to North Africa, always at strategic, elevated points and at the crossroads of several routes. In Morocco there are still remains of 8 fortifications: Agwidir and Taghjijt in Guelmim; Irhir N’Tidri and Tazagurt in Zagora; Aufilal and Jebel Mudauar in Errachidia; Tasghimut in Marrakech; Amergu in Taunat. It so happens that except for the first one, in the ancient Noul Lamta (today Asrir-Tighmert), which was built in the 11th century in adobe and mud brick, the rest are made of stone, as is the case with the constructions of Adrar (Azugui, Atar, Chinguetti and Ouadane).

Almoravid fortifications in Morocco

The power shown by the Almoravids, capable of ordering and controlling such a vast territory, with routes of more than 2,000 km, contrasts with the heritage they left in the city of Ceuta. Except for some ceramic remains, no evidence of fortifications has been found, not even of residential constructions. This does not mean that the city was not important during the 11th and 12th centuries, since during that period illustrious figures such as the jurist Cadi Ayyad, the saint Sidi Bel Abbas as-Sabti, the geographer al-Idrisi or the second emir of the dynasty Ali ibn Yusuf (who also grew up in the city) were born. This circumstance can serve to understand the scope that the fortification built in the 10th century by the Umayyad in Ceuta could have had, which was in use until the Portuguese decided to build the Royal Wall and Moat in the 16th century. Therefore, it is quite possible that the Almoravids did not need to build or reinforce the walled enclosure as they had the technical and economic capacity (demonstrated along the caravan routes) to build new fortifications if they had been necessary.

Caliphal gate of Ceuta (Spain) built in the 10th century

Credits texts, photos and drawings: Carlos Pérez Marín