06. Research methodology

The knowledge acquired and presented here has been based primarily on field experience, without being limited to academic methodologies, which has given us greater freedom by not depending on funding (only 5% of the financial resources used since 2010 come from grants) or fixed deadlines to carry them out, creating digital research platforms with which to share knowledge and experiences, and organising cultural activities.

6.01 Marsad Drâa

In 2013, I created an online and open research platform on the desert called Marsad Drâa (Drâa Observatory). It was started without any concrete plan of what was going to be done in the short or medium term, but it was about gathering information found in libraries and on the Internet or collected on the ground. In reality, it was about finding an excuse to continue going to the desert after seeing the possibilities it offers in many fields thanks to the study trips carried out between 2011 and 2013 with my students from the National School of Architecture of Tetouan (Morocco), with whom we tried to solve the urban and architectural problems posed to us by the authorities. That is why, after leaving teaching in Tetouan, my interest focused on getting to know the desert better, aware that it was not going to be enough to understand the type of architecture found in the oases, but that it was necessary to be interested in tribal organisation, their cultures, history, agriculture, water management, geology, history… Even knowing and trying to find solutions to the problems arising from desertification, an issue that is not exclusive to the lack of rainfall or the drop in water tables, other components come into play, such as sociological and economic aspects. Among the research carried out with former students or with the local population itself, there is the project to stop the advance of the dunes and the water catcher for ambient humidity and the structure to create new oases, all three in Tissardmine, Errachidia and carried out in collaboration with Café Tissardmine, always using local techniques such as rammed earth walls or the construction solutions used by nomads for their tents.

Dune barrier, Tissardmine (Errachidia, Morocco)

Water catcher, Tissardmine (Errachidia, Morocco)

Our work with architecture students from Tetouan led us to discover a density of heritage in the Drâa valley in Zagora that is not visible from the national road and that deserved to be studied. In 2015, I began work on the Architectural Guide Map of the Drâa Valley, thanks to the collaboration of CERKAS (Centre for the Conservation and Rehabilitation of the Atlantic and Sub-Atlas Architectural Heritage, belonging to the Ministry of Youth, Culture and Communication of the Kingdom of Morocco). The work took place over a period of 6 months and the objective was to gather as much information as possible on the 299 ksars, kasbahs and zawiyas of the 6 palm groves that make up the valley on a Google Maps. This research allowed a better understanding of the architecture but also of the land use, agriculture, irrigation systems and management, and the cultures of the different tribes (Draua, Berbers and Arabs) that still inhabit this geographical space, which is essential to understanding what a Saharan port is and the importance that the caravan routes once had.

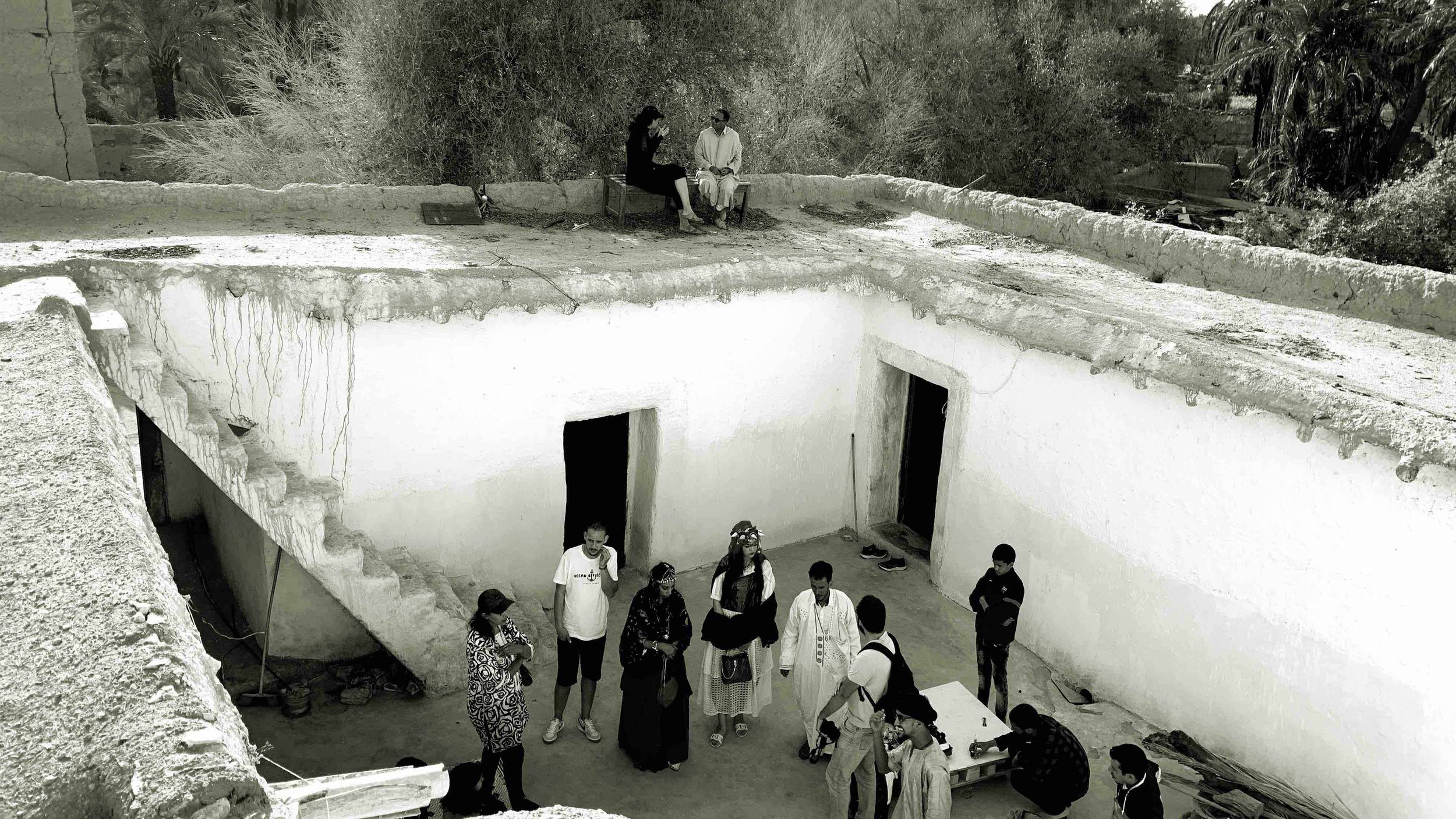

Workshops were also organised for architects and historians with the Labina association in Marrakech to learn more about the built heritage at the crossroads of caravan routes, specifically in Tasghimut, near Aghmat (Marrakech) or to rehabilitate the mosque of the madrasa of the Tamnugalt last in Zagora, the aim of which was to prevent the building from deteriorating even further and collapsing, although it was important to be able to live for 10 days in the Mezguita palm grove and in the Kasbah des Caïdes, within the ksar, with whom we organised the workshop.

More information at Marsad Drâa.

Tasghimut workshop (Marrakech, Morocco)

Tamnugalt workshop (Zagora, Morocco)

6.02 Caravane Tighmert

In 2013, we organised workshops for young artists and architects together with the inhabitants of the Tighmert oasis in Guelmim (Morocco). Warsha Sahara (Desert Workshops) was the first attempt to exchange knowledge between young professionals and oasis inhabitants. In 2014, another workshop was organised with the same objectives, but in a completely different setting, the nomadic village of Tissardmine.

Warcha Sahara Tighmert, (Guelmim, Morocco), 2013

Warcha Sahara Tighmert, (Guelmim, Morocco), 2013

Warcha Sahara Tissardmine, (Errachidia, Morocco), 2014

Warcha Sahara Tissardmine, (Errachidia, Morocco), 2014

Both workshops showed the potential they had to investigate, from an architectural and artistic point of view, multiple aspects of the different types of habitat that can be found today in southern Morocco.

In 2015, and as a result of the floods suffered by the oasis of Tighmert in 2014, during which the population was cut off for two weeks, Ahmed Dabah and Bouchra Boudali proposed to me to organise together a festival with artists where children and young people could enjoy cultural activities (workshops, exhibitions, concerts, conferences...) and thus forget the ravages caused by the floods. After an initial festival, the event developed, without any institutional funding, only with private contributions and from the organizers themselves, towards a meeting between artists, researchers and inhabitants of the oasis.

Although Tighmert is a small oasis (6 km long and 1.5 km wide at its widest point), with a population of around 4,000 and an architecture based on single-family houses made of adobe and rammed earth, with two small kasbahs, its importance throughout history was much greater than its tangible and intangible heritage suggests. In fact, its original name was Noul Lamta, one of the three Moroccan Saharan ports and the “capital” of the nomadic Lamtuna tribe, one of the three founders of the Almoravid dynasty in the 11th century. It is very likely that the two oases of Tighmert and Asrir formed a single one, but what is known is that the fortification of Agwidir was built by the Almoravids in the 11th century and that near the Noun River archaeologists Jorge Onrubia and Youssef Bokbot have found evidence of constructions corresponding to an urban settlement from the 9th century. Despite the absence of an architectural heritage of great value, it is likely that Noul Lamta is one of the ancient cities still occupied in Morocco. The lack of excavations has not allowed us to advance in a dating of the exchanges carried out with the southern shore of the Sahara, which archaeologists have attested, to at least, from the 11th century, but it would not be strange if trans-Saharan trade had developed much earlier.

In this historical and contemporary context, we propose to the participants of Caravane Tighmert to carry out research on aspects of the past or of daily life, both in the oasis and in its surroundings, without any pressure to produce any artistic work, since, as we have no funding, we are not obliged to justify their stay. We do encourage them to do workshops with children and young people, but with the intention of exchanging knowledge and, above all, to delve into the complex society of the oasis, with a majority Sahrawi tribe, Azuafit (the eastern part of the oasis is occupied by and a Berber tribe, Aït Ahmed). The presence of artists from the region, from other Moroccan cities and from abroad has also enabled an almost radical change in the perception that the inhabitants themselves have of their oasis and its history, thanks to the interest shown by the participants in architecture, heritage, agriculture, irrigation, geology, nomadism, history, slavery, tribal organisation, cultural connections with the Adrar in Mauritania, traditional dances and music, poetry, the Hassanian dialect… Each request from the participants was answered with information that the members of the team (Ahmed Dabah, Abderrahmane Sayad, Hamza Sabar, Ahmed Sabar, Slamat el-Mkhaire, Ghassan Kaaibich, Mokhtar Elbelawi, Mohamed Arejdal, Bouchra Boudali…) already had. If we were unable to provide an answer, we accompanied them to talk to those who could provide information. Since the first edition in 2015, all of us, participants and organizers, have been learning as new questions arose in the conversations held both in the traditional houses used as cultural centers and in the nomadic spaces where we stayed two or three nights to have a completely different perspective of the oasis, both from the geographical and anthropological point of view, as we had chance encounters with the nomads of the area.

More information at Caravane Tighmert.

6.03 Caravane Ouadane

In 2020, a group of friends decided to celebrate the tenth anniversary of my first trip to the desert, to the oasis of Tighmert (Guelmim, Morocco) in 2010. At first, the idea was to repeat the same route, but precisely the artist friend from Guelmim who invited us to discover the oasis, Mohamed Arejdal, told us that we should not remain stuck in the past and that we should always move forward, go further, and what better than to visit Mauritania. We automatically agreed to the proposal because it would allow us to get to know another region of the Sahara, to see on the ground what remained of the relationships woven by the caravans in times past and, above all, to explore the heritage of the Adrar region, which is supposed to have been the origin of the Almoravid dynasty.

A week before leaving North Africa by car with the artist Younès Rahmoun and the cultural activist and co-founder of Caravane Tighmert, Ahmed Dabah, a message from a gallery and concept store owner in Nouakchott asking for information about the Slaves Festival held every summer in Tighmert allowed us to participate in a meeting with Mauritanian researchers and artists that she herself organised upon our arrival in the capital. This meeting, together with recommendations to visit Ouadane instead of Chinguetti based on our interests, led to new meetings with cultural actors such as Isabel Fiadeiro from Zeinart (art gallery in Nouakchott), Mohamed Ali Bilal from Teranim (association working to preserve the culture of former slaves) and Zaida Bilal from Auberge Basque in Ouadane (a reference in the cultural, social and tourist development of her city). Sharing so many interests, we quickly agreed to organise the following year Caravane Ouadane in this oasis of Adrar founded in 1146 by three nomads, two of whom had travelled more than 2,000 km years before to study in Ceuta with Cadi Ayyad. This is a good example of how the territory linked to the desert and caravan routes should be considered, not as regions, but as trajectories, as argued by François-Xavier Fauvelle (L’Afrique Ancienne. De l’ Acacus au Zimbabwe). Only in this way we can understand the connections between Ceuta and the Sahara and the heritage built to control these trajectories, as we have seen above. The importance of Ouadane lies in its position on the trajectories that link southern Morocco with Mauritania, Senegal and Mali. After crossing the Sahara, the first "logistical centre" was that of Adrar and from Ouadane, the following stages were determined by the cities of Tidjikja, Tichit, Oualata and Timbuktu, for many centuries the nerve centre of the caravan trade on the southern shore of the Sahara, depending on the centuries, in competition with Audagost and Kumbi Saleh (capital of the Ghana Empire), both in Mauritania.

As with the Tighmert oasis, the organisation of an annual cultural event has allowed us to visit Ouadane, and Mauritania, every year since 2020, finding some answers to the questions posed from the northern shore of the Sahara, but also bringing to light many new issues, thanks to the scientific work of the French protectorate, discussions with Mauritanian researchers and field work in Nouakchott, Atar, Chingueti and Ouadane.

From the beginning, we were clear that Caravane Ouadane could not be a copy of Caravane Tighmert due to the different conditions of both territories and despite sharing history and heritage. It is true that we started from the experiences of each of the organisers, but the model was to be built edition after edition, depending on the possibilities and involvement of the local population. One major difference with Tighmert was the institutional funding from the Spanish, German and French embassies, the European Union, the Alliance Française, the Vergnol Foundation and some private donors. The budget increased from €3,000 to €5,000 between the first and third editions, to cover two nights of concerts open to the public and accommodation and food for the artists and organisers for two weeks.

We proposed to the participants the same objectives as in Tighmert, to carry out research on topics from Ouadane or its surroundings and to carry out workshops with children, young people or adults from the oasis, but it was not mandatory to produce any work since the objective was to learn and exchange knowledge that would allow a better understanding of the desert over time. In this sense, Caravane Tighmert and Caravane Ouadane complemented each other by allowing artists to work and research on similar themes but in different geographies; traditional and contemporary architecture built in stone; oasis agriculture based on acacia and not palm trees; the relationship between sedentary urbanism and nomadic settlements; the importance of artistic education in local culture; cultural connections with other territories through dance, music and poetry (in both Tighmert and Ouadane the main dialect is Hassaniya), the contemporaneity of these artistic expressions; the implications of tourism; tribal organisation; history; crafts, their relationship with ways of life and their evolution; the concept of cultural development, heritage and museum; the symbolism of henna tattoos; the visibility of former slaves and black tribes in today's society; relations with other oases and other territories...

More information at Caravane Ouadane.

6.04 Project Qafila

The constant mention of caravans and nomads in each of the Saharan ports could be considered as marketing tools used to attract the attention of tourists. However, from the first meeting with nomads in September 2012, it was clear that nomadism, even within the borders, still existed. It was no longer a question of families (a term used to describe the division of a tribe) or even fractions with up to 400 tents that moved their camp between the High Atlas and the Senegal River depending on the rainfall and therefore the grazing. Nowadays it is difficult to find more than three or four tents in a single family unit in Morocco; in Mauritania the nomadic population is larger and camps can reach 10 or 15 tents but there are no longer large camps as in the last century.

In his thesis (Le Sang et le Sol. Nomadisme et sédentarisation au Maroc), anthropologist Ahmed Skounti explains how the caravan trade and extensive nomadism in the western Sahara region began to decline first in the 1930s, when France began to have a greater presence in the pre-Saharan areas (basins of the Noun, Drâa, Gheris and Ziz rivers) and abolished the special passes for nomads to cross from the French zone to the Spanish (due to the attacks suffered by their troops by tribes that later took refuge in the Spanish area). Later, the drought that lasted from 1980 to 1984 caused the sedentarisation of many nomadic families. The event that put an end to extensive nomadism and caravan trade was the war between Morocco and Polisario in the early 1990s.

During the first conversations with the nomads (near the oases of M’hamid el-Ghizlan and Tighmert in Morocco) I learnt that the old caravan routes were still used by them, which was logical to a certain extent since they still depended on the water wells for their travels. In Morocco, these travels are mainly made with off-road vehicles like the Land Rover Santana, which have replaced camels as a means of transporting goods and people, while in Mauritania, the camel still plays a role in the displacements of nomads.

Nomads in Smara

Nomads in Ouadane

These first meetings were key to understanding that despite certain research works from the time of the protectorate and today, it was still possible to learn first-hand about nomadic ways of life and how they navigated the desert. From there arose the idea in 2016 to begin practical research on caravan routes, and therefore, on nomads, travelling these routes with them. At no time it was considered to develop the work beyond the Moroccan border, but the start of Caravane Ouadane would allow us to extend the study area to Mauritania.

Thanks to Internet, artists and overall to researchers from other countries exchanging information obtained on the web, in old publications, in libraries of cultural centres in Gardaia (Algeria), in universities in Khartoum (Sudan) or in the field (even if they were related to contemporary immigration routes), with the contributions of Antoine Bouillon, Pau Cata, Amado Alfadni and Eleonora Castagnone, we were able to create this map with the routes of the caravans of the Sahara, trying to make the route between different points as close as possible to that which a nomad would take today, based on the experience of Project Qafila (Caravan Project). At the end of each caravan we uploaded the information produced on the Internet; diaries, photos, drawings, videos, conversations, interviews… Everything we learned during each caravan forced us to reread the reference books on the history of these regions, since the experience made us see and understand aspects that went unnoticed after a first reading. The nomads taught us to think like them, and the territory and its heritage took on a completely different character than in the books.

Caravan routes of the Sahara

The preparation of our caravans was done using different ancient plans, which aroused our curiosity about the different ways of representing the desert. Firstly, thanks to the maps of the African continent drawn up at the end of the 19th century, and also to the plans drawn up during the 1930s, 40s and 50s by the different armies that had interests in these territories, indicating paths, routes, water wells, water courses, topography, type of terrain… Often, the information collected was much more useful than aerial photographs in which all these details were not represented.

Maps of the African continent by Charles Soller (1888)

Maps of the African continent from Nordwestliches Afrika (1863)

Maps of the African continent by Charles Soller (1888) with indication of the route taken during Qafila Khamisa

American Army blueprints (University of Texas at Austin) used in Qafila Oula

The most modern and interesting are those drawn up by Théodore Monod until the end of the 20th century. Some of these plans have encouraged us to choose routes for our caravans.

Théodore Monod's expeditions in Mauritania and Mali between 1934 and 1935 (source: Le Monde Diplomatique)

Théodore Monod (1902-2000) is considered one of the greatest specialists in the Sahara desert. Despite his initial training as a naturalist specialising in marine biology, his interest and curiosity about the desert eventually caught up with him and he dedicated his long life to travelling through almost all the regions of the Sahara, first with caravans, then with expeditions. It was Nefaa, the guide of the 5th caravan (Qafila Khamisa) between Chinguetti and Tidjikja in Mauritania, who explained to me the difference between caravans and expeditions. Expeditions can be military or scientific and they pass through places where there is neither water nor food. It is precisely the food of the camels, more than the water, that determines the length of the journey, since camels can last weeks without drinking but they have to eat every day, so it has to be transported and this implies a greater number of camelids. Nefaa knew what he was talking about. He had personally met Théodore Monod and one of his brothers had participated in the expeditions that he had started from the Adrar. Being able to speak with someone who had known Monod allowed me to compare the image that his written work and documentaries gave of him; both coincided, he loved the desert and was appreciated by the people who knew him. Perhaps, one of the greatest lessons from his work and which consolidates the idea that another type of scientific research is possible, was his consideration of what a scientist is. His son, Ambroise Monod, explains in the documentary, Théodore Monod, une météorite das le siècle that, for his father, a researcher is not someone who is paid to do research, but anyone who searches, even if they don’t find anything. In his manual Conseils aux chercheurs (Advice to Researchers), published in 1941 by the French Institute of Black Africa (IFAN), he explained that anyone who wanders around, finds something that questions them, picks it up, takes it with them, notes the place and date, and sends it to IFAN, is, for him, a researcher. In a certain way, Théodore Monod has helped us to corroborate our attitude when it comes to researching in the desert with the different initiatives, even if they do not correspond to academic methodologies, which allows us to modify the planned objectives or add new ones on the fly.

Returning to the relationship between heritage and territory, practical research on caravans has been fundamental to understanding the importance of water wells in certain regions because they are the ones that determine the route. Qafila Khamisa's initial route was Tichit - Ouadane, trying to recreate one of Monod's expeditions. Zaida Bilal (co-founder of Caravane Ouadane) helped us organise it by contacting the guides who would show me the way. Two members of the Nemadi tribe (the only one that still hunts with dogs in this part of the Sahara) knew the route, but to be sure, Zaida asked them which route to follow and they sent her the route with 10 stages, each one corresponding to the name of a well. When I tried to locate them on the maps, I understood the relationship between the supply points, the topography and the geology. The wells were on the edge of a rock formation that corresponds to the Adrar plateau. In the end, because one of the nomads fell ill, we had to improvise another route, Chinguetti - Tidjikja, running out of time to reach Tichitt due to the time spent organising the new caravan. In any case, the route was almost identical but in the opposite direction. On the contrary, the route we had imagined before contacting the Nemadi nomads corresponded to one of Monod's expeditions, where there were practically no water wells, and it was not a usual route for nomads and therefore for caravans.

Possible routes for Qafila Khamisa in Mauritania, Tichitt-Ouadane and Chinguetti -Tidjikja

Caravans, sometimes with artists and sometimes alone accompanied by one or two nomads, involve several intensive courses of learning (geography, geology, biology, history, heritage, language, music, dance, poetry, architecture…) and when comparing those carried out in Morocco and Mauritania, the negative impact of tourism in the desert is observed, sometimes ridiculing aspects that were once important in the identity of the nomads. Thus, while in Morocco tourists camp in a setting taken from a colonial adventure film and ride camels using saddles to carry goods, in Mauritania nomads continue to travel without even setting up tents and using in their daily journeys saddles made of taichot wood (a variety of acacia) covered with leather decorated with geometric motifs. In Morocco these saddles have been left for the camel races organised during festivals or museums. In a certain way, tourism continues to trivialise the desert, making ancestral ways of life disappear, which are not only remnants of the past but also teach us attitudes that can help us adapt to any environment, no matter how hostile it may be.

Nefaa preparing the camel's saddle during Qafila Khamisa in Mauritania

One of the most interesting aspects of researching caravans is the unexpected encounters with nomads. After long polite greetings, they ask a question that is systematically repeated every time we meet one: what tribe are you from? The conversation continues with another essential question: where are you going and where are you coming from? The next one was related to water, provisions and if we needed anything. It is curious that apart from the first question, the others are very common when two sailboats meet in port or in the middle of the sea. These conversations between nomads could last a few minutes, a night or even several days. Sometimes, especially if they knew each other, there have been nomads who have accompanied us for two days for the simple pleasure of catching up with their friend. It is in these encounters that one becomes aware of the importance and meaning of belonging to a tribe.

The direct or indirect settlement of the nomads, in the sense of being provoked, allows us to go to them again and again and ask them questions that arise during the caravans. This is what happens with Mokhtar, from the Aarib tribe, who nomadises now around the oasis of M’hamid el-Ghizlane in Zagora (Morocco) but he used to take part in caravans that crossed the Sahara till the 80s. In the first encounter he told us some passages and anecdotes during his journeys, in the second he recounts the journeys to Sijilmasa (Rissani), Guelmim and even Timbuktu, giving recommendations on the location of wells and the quality of their water. On other occasions he gives us a lesson on astronomy, from a mythological point of view but also focusing on astronomical aspects. In 2016, right after Qafila Oula (the First Caravan), instead of a story, the encounter became an interview in which I asked him for more precise information about the daily life of the caravans, their composition and number, the characteristics of some regions, the type of merchandise he transported. In later years, during the caravans we were able to talk both with the nomads who were our guides and with those we met on our journey, asking them about what it means to be a nomad today, the difficulties that it entails, the education of their children, the economic means they have, the products and animals they trade, the making of their own tents, the geographical areas in which they move, their relationships with sedentarisation…

One of the themes related to nomads that interests me the most is their relationship with architecture (and non-architecture), how in their travels, they are use tents to be protected from the wind and sand, and from the rain, or how important is the shade of the trees, becoming habitable spaces, that change with the sun position, where it is possible to take a break for lunch during the hottest moment of the day. But when they travel alone or need to move fast they don’t even use tents adapting themselves to weather conditions without protection, submitting themselves to nature. If they are accompanied by their families, it is very likely that they carry a tent. There are still traditional ones (made from camel or goat hair) but little by little those made from reused fabrics are becoming more popular, generally melfha, a very light and breathable cotton fabric with brightly coloured patterns that is used throughout the Sahara. These tents are much lighter and therefore easy and quick to set up. However, nomads usually have, somewhere in the areas they frequent, constructions (on rammed earth or stones) in which they can leave their belongings safe from animals, if they ever built a kind of cabin with tree branches they can use barbed wire to keep animals away. And if they need to keep valued goods, like cereals they build granaries with metal sheets recycled from fuel drums.

Overnight camp during Qafila Khamisa in Mauritania

Sometimes nomads have real homes, in villages and cities, which they use for several months of the year, generally so that their children can attend school or to take shelter in the hottest months. It is very interesting how they organise the home spatially and how they inhabit the different outdoor spaces based on the shadows cast by the trees they lean against or those generated by the construction itself. In reality, since nomads live mainly outdoors, using tents in case of wind with sand, rain and extreme temperatures, when building a home, there will be few occasions when they will stay in covered rooms. The patios and outdoor spaces with shade will be the real rooms.

Nomad near Mrimina (Tata, Morocco)

Nomad near Foum Laachar (Zagora, Morocco)

Nomad near Zagora (Morocco)

Sketch of the home of the Kabbaj family, sedentary nomads in Tafraut (Errachidia, Morocco)

Here is a sample of what the desert can teach us about the architectural heritage of other places. Fernando Chueca Goitia explained in his book Invariantes Castizos de la Arquitectura Española, with regard to the Alhambra, that the courtyards of the palaces must be understood in the following way:

The garden, in turn, is delimited like a habitable room whose ceiling is blue.

The house of Salim's sister (Qafila Oula's guide) could be defined as a series of spaces delimited by shadows and whose ceiling is blue. I would also add blue and stars, since the views of the constellations from the "bedrooms" of the nomads are part of their own identity and when they sleep under a roof they feel like they are locked in a prison.

More information at Project Qafila.

07. Epilogue

The main element of the architectural heritage of the Sahara is the water well. In completely desert regions, that is, with no oasis, the wells determined the routes that the caravans had to follow, with all the consequences that this implies; the need to exercise control over these points; guaranteeing the safety of the routes between adjacent points (exercised by the tribes of each affected territory); tax collection for the use of water or for the escort required during transit; channelling of flows; assistance and logistics for travellers…

In the Saharan regions, although there are kasbahs, ksars, zawiyas and marabouts, of considerable size and architectural interest, it is the well that determines the organisation and development of these constructions. Normally the wells are inside the mosques and if the ksar is so large that it contains more mosques, then the collective water supply points will increase. On a larger scale, the occupation of the valleys by the aforementioned constructions established a whole network of water wells, almost always associated with buildings of a certain size. These regional units around a river also have connections between them, facilitating the transit from one region to another. When it comes to crossing the Sahara, where kasbahs, ksars and zawiyas no longer exist, it will be the water wells that determine the route and the different regions within the desert.

Making an analogy with Italo Calvino's character from Invisible Cities (Marco Polo), who argued that if the stones of a bridge were not described, there would be no bridge, we can say that without these apparently simple and banal holes dug in the ground in the middle of the desert to obtain water, there would be no caravan routes, nor any exchange between the Sahel, the Maghreb, the Middle East and Europe. This is why if we want to understand the north of the African continent, we will have to know and accept the importance of these water wells, otherwise our understanding will be partial.

08. Bibliography

Almela, Iñigo Arquitectura religiosa saadí y desarrollo urbano (Marrakech ss. XVI-XVII)

Batttesti, Vincent Les possibilités d’une île, Insularités oasiennes au Sahara

Bens Argandoña, Francisco Veintidós años en el desierto: Mis memorias y tres expediciones al interior del Sáhara

Caillé, René La ville de Temboctou

Calvino, Italo Las Ciudades Invisibles

Capel, Chloé Jebel Mudawwar : une montagne fortifiée au Sahara. Site étatique ou site communautaire?

Caro Baroja, Julio Estudios saharianos

Chueca Goitia, Fernando Invariantes Castizos de la Arquitectura Española

Cressier, Patrice Dar al-Sultan, les confins de l’Empire almohade

Cressier, Patrice La forteresse d’Agwīdīr d’Asrir (Guelmim, Maroc) et la question de Nul Lamta

De Foucaud, Charles Reconnaissance du Maroc

Douls, Camille Cinq mois chez les Maures nomades du Sahara occidental

El-Hamel, Chouki Le Maroc Noir: Une histoire de l‘esclavage, de la race et de l’islam

Fauvelle, François-Xavier Fauvelle (dir) L’Afrique Ancienne: de l’Acacus au Zimbabwe

Jacques-Meunié, Denise Cités caravanières de Mauritanie: Tichite et Oualata

Jacques-Meunié, Denise Le Maroc saharien des origines à 1670

Je me casse au soleil Cartes Topographiques du Maroc

Kölbl, Otto / Boussalh, Mohamed Inventaire du patrimoine architectural de la vallée du Drâa

Le Monde Diplomatique, Théodore Monod le Saharien

Lesourd, Céline Faire fortune au Sahara

Magnavita, Sonja Sahelian crossroads: Some aspects on the Iron Age sites of Kissi, Burkina Faso

Magnavita, Sonja The oldest textiles from sub-Saharan West Africa: woolen facts from Kissi, Burkina Faso

Marcos Cobaleda, María (coord) Al-murabitun: Un imperio islámico occidental

Marty, Paul Les tribus de la Haute Mauritanie

Matoušková / Pavelka / Smolík / Pavelka Earthen Jewish Architecture of Southern Morocco: Documentation of Unfired Brick Synagogues and Mellahs in the Drâa-Tafilalet Region

Mattingly / Bokbot / Sterry / Cuénod… Long-term History in a Moroccan Oasis Zone: The Middle Draa Project 2015

Messier, Ronald / Miller, James The last civilized place. SIJILMASA and Its Saharan Destiny

Monod, Théodore L'Émeraude des Garamantes

Monod, Théodore Méharées: Explorations au vrai Sahara

Naïmi, Mustapha Le Bassin du fleuve Oued-Noun

Naïmi, Mustapha (coord) Sidi Waggag b. Zalluw al-Lamtî aux origines du malékisme étatique nord-ouest africain

Navarro Palazón, Julio / Trillo San José, Carmen Almunias. Las fincas de las élites en el Occidenteislámico: poder, solaz y producción

Nixon, Sam Refining gold with glass e an early Islamic technology at Tadmekka, Mali

Nixon, Sam Tadmekka. Archéologie d’une ville caravanière des premiers temps du commerce transsaharien

Nixon, Sam The great trading centre of Tadmakka

Ould Cheikh, Abdel Wedoud L'Adrar et ses villes anciennes : histoire, habitat, société

Ould Cheikh, Abdel Wedoud Note sur l’esclavage en Mauritanie

Ould Cheikh, Abdel Wedoud / Lamarche, Bruno Ouadane et Chinguetti. Deux villes anciennes de Mauritanie

Pérez Marín, Carlos Textos, conferencias e investigaciones en carlosperezmarin.com projectqafila.com, marsaddraa.com, caravanetighmert.com y caravaneouadane.com

Pliez, Olivier Nomades d'hier, nomades d'aujourd'hui. Les migrants africains réactivent-ils les territoires nomades au Sahara?

Rosière, Pierre Selle particulière des Tirailleurs Sénégalais Méharistes de la Mauritanie

Ross, Eric A historical Geography of the Trans-Saharan Trade

Sahara Español-Gobierno General de la Provincia Sahara Español, Ifni y sus regiones inmediatas de zona francesa del S. Marroquí y Mauritania o Sahara Occidental Francés Croquis nº 2 (1930)

Shell Carte du Sahara (1950)

Simenel, Romain De Bojador à Boujdour. Nomades, poètes et marins du Sahara Atlantique

Skounti, Ahmed Le Sang et le Sol: Nomadisme et sédentarisation au Maroc

Terrasse, Henri La forteresse almoravide d’Amergo

Terrasse, Henri L'art de l'empire almoravide: ses sources et son évolution

The University of Texas at Austin Perry-Castañeda Library: Morocco Maps

Unesco Nomades et Nomadisme au Sahara

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Maps of Africa to 1900

Villalba Sola, Dolores (coord) Al-muwahhidu. El despertar del califato almohade

Wilbaux, Quentin La médina de Marrakech

Credits texts, photos and drawings: Carlos Pérez Marín